Independence has brought us political freedom, but a vast majority of the poor still suffer financial apartheid.

Vikram Akula

Microfinance can change the face of poverty in India, but for that the stakeholders must come together and learn to think big

Independence has brought us political freedom, but a vast majority of the poor still suffer financial apartheid. While middle and upper classes can get a loan, write a cheque, open a savings account, buy insurance, and send a wire transfer, most poor people cannot. Their primary source of credit is extortionist loan sharks and pawn brokers. These groups charge rates that average 36 to 60 per cent annum (in the case of daily finance, as high as 3,000 per cent) and put the poor in a debt trap.

Meanwhile, most banks don’t lend to the poorbecause they don’t have collateral and because it is costly to service tiny loans of Rs1,000 to Rs10,000. Moreover, when it comes to other financialservices, the poor have virtually no access whatsoever.

The microfinance movement has tried to change that. It is a movement that first emerged in India 30 years ago and has ramped up significantly in the last decade. It includes thousands of institutions, from small NGOs to national-level regulated microfinance institutions (MFIs). It includes the public sector Regional Rural Bank self-help group channel as well as the private retail MFI channel. Together, these channels reach about 1 crore families.

Numerous studies have shown that microfinance enables the poor to increase income, build assets, and get out of economic poverty. At SKS, we see this daily among the nearly 8 lakh borrowers we serve across 13,000 villages and slums in the country.

But for all the impact that the movement has made, it still reaches only a small fraction of the poor — an estimated 15 per cent — and the movement has provided only an estimated 10 per cent of the credit needed by the poor and even less of other financial services. The blight of financial apartheid continues. In order to change that, MFIs, Banks, and the government need to think about the sector in a radically different way.

The first group is MFIs. Today, nearly 90 per cent of MFIs serve fewer than 10,000 clients. MFIs must start envisioning servicing lakhs of poor instead of thousands. To do this, MFIs need to overcome some ideological hang-ups. Since most MFI practitioners have social sector roots (including myself), we have traditionally looked at ‘business’ as a bad word. We need to overcome those ideological blocks. We need to look to and learn from international companies like McDonald’s and Starbucks and domestic players like Airtel and Big Bazaar.

These companies know how to scale and the microfinance sector needs to learn those techniques. We also need to move beyond our paper passbooks and dusty ledgers and understand how these companies use technology to ramp up. At SKS, we’ve taken a small step in this direction by setting up standardised scalable business processes and deploying technology; as a result we roll out 30 new branches and enrol 65,000 new members a month. That’s good, yes. But it is a drop in the bucket.

The second group that needs to act radically different is banks. Bankers must look at the poor not as a group that needs charity but as an entrepreneurial segment that provides them a business opportunity. As a microfinance movement, we have proven that the poor are credit worthy, and they will use the credit productively, earn income and repay. At SKS, for example, we have disbursed over Rs900 crore, have taken no collateral, and have a 99 per cent repayment rate.

Commercial bankers need to start providing more financing to MFIs (or increase lending to the poor directly) and charge a lower interest rate. To date, only a handful of banks have come forward in a large way, including HDFC, CITI, and ICICI — to name a few. But we need more, especially public sector banks, which have largely stayed away from financing the MFIs.

The final — and perhaps most important — group is the government and RBI. The RBI must bring back the brilliant business correspondent regulation of 2005 that had enabled regulated NBFCs to conduct banking on behalf of banks. This policy had enabled them to finally have access to additional products, such as savings. But it was rescinded in 2006. If the NBFC-Business Correspondent regulation can be re-instated, the poor will again have access to financial services. Savings, in particular, is crucial as poor people have no safe place to save and end up, literally, putting their hard-earned cash under their mattress or spending on consumption or making unproductive gold purchases.

If the poor had access to banks through business correspondents, the investment they make in gold could instead flow into the economy and stimulate growth — and, as important, the poor would be able to build up the savings required to get out of poverty. Just as there is a new economy, a new entrepreneurial spirit among the poor, a new breed of politicians and regulators, there is also a new generation of NBFC MFIs. The government needs to harness, not hinder, them.

In this regard, the attempt of the parliament to bring in a microfinance bill is laudable, but since NBFCs and Section 25 companies (which serve 80 per cent of microfinance clients) do not fall under its ambit, it essentially misses the mark. As for what our elected politicians can do, they can make a better attempt to understand poor people’s financial needs — how devastating it is to have to turn to a village loan shark, how a health crisis puts a family without health insurance in a downward spiral, how difficult it is to build a home without access to finance, how hard it is to save without a safe place to put earnings aside.

If there was a better understanding of the needs of the poor then, perhaps, policy measures will emerge that will help us leap, not hobble, towards financial inclusion. Hence all of us have a role. Only if we expand our vision and work together, will we be able to expand the promise of economic freedom for those crores of families who have been left behind.

Vikram Akula is founder and CEO, SKS Microfinance.

![submenu-img]() 'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case

'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…

Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…![submenu-img]() You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why

You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...

Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…

Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...

Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react

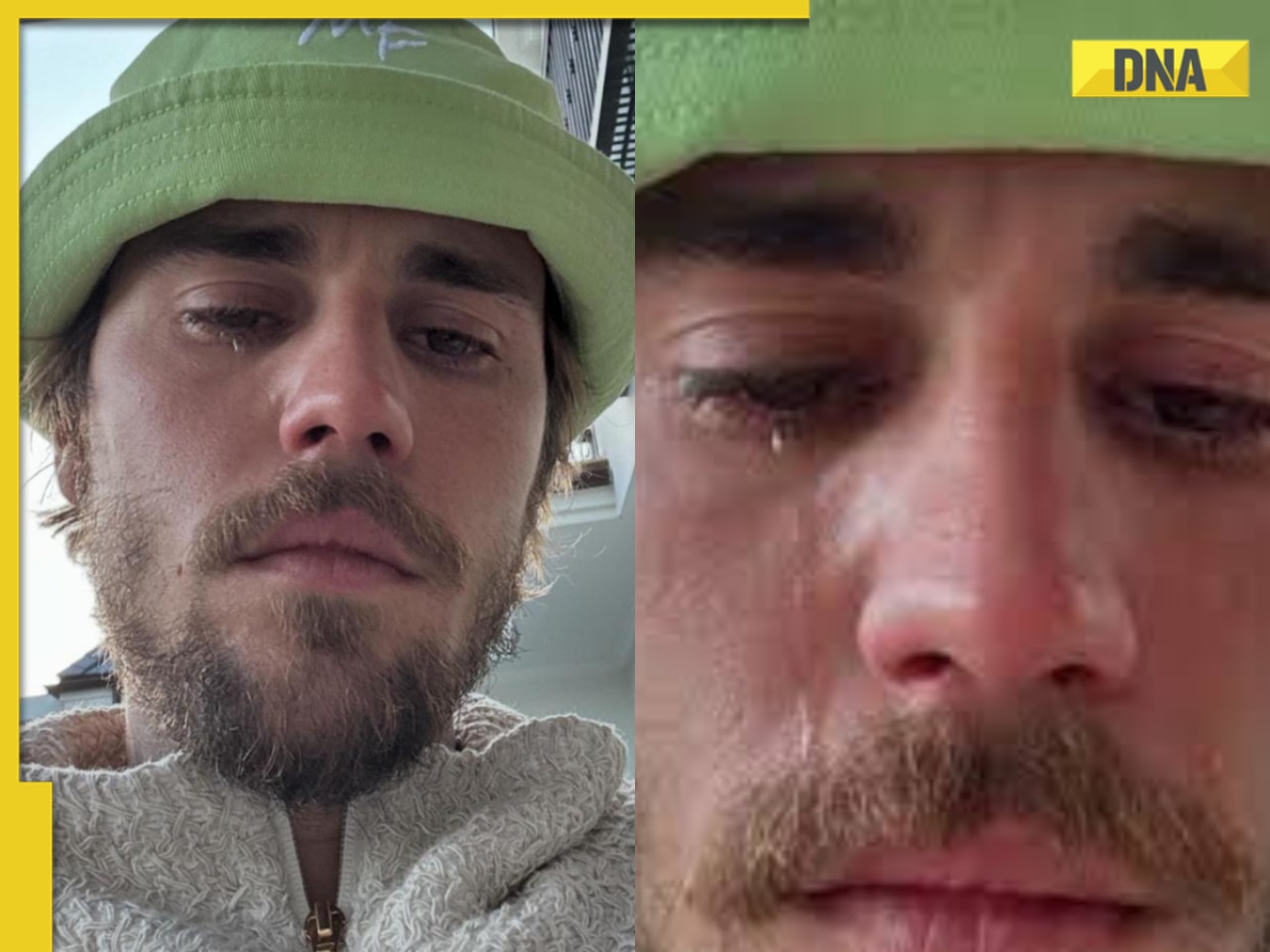

Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react![submenu-img]() This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore

This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore![submenu-img]() This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..

This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..![submenu-img]() Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute

Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad

IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets![submenu-img]() PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup

PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans

IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)