A rise in adoption figures in recent times indicates many are accepting the practice. However, legal handicaps make both adoption and foster care a bit difficult.

A rise in adoption figures in recent times indicates that more and more people are beginning to accept the practice. In fact, the trend has gained much impetus in Maharashtra, considering the fact that several voluntary adoption agencies have been set up all across the state. However, Seemaa Kamdar finds that certain legal handicaps make both adoption and foster care a bit difficult

‘Mummy, when are we taking bhai home?’ asks a child of five, jumping up and down excitedly. Her mother smiles indulgently and, with one eye on her infant son nestling in her arms, beams, “soon.” This scene is not taking place in a maternity home but in the adoption cell of Vatsalaya Trust, an NGO at Kanjur Marg. The couple is here to adopt a son, after they adopted a girl from the same place over four years ago.

Adoption in India is hot and happening. Agencies swear that the figures have swelled over the past few years, thanks to greater acceptance of the practice and positive press coverage. Even as a rise in the number of adoptions is being registered and waiting periods at adoption cells increase, stories of single adoptive parents are also being heard.

Maharashtra, in particular, has been proactive with regards to adoptions. It is the only state with four voluntary adoption agencies (VCA) — other states have only one — to coordinate efforts with NGOs as and when required. The state has about 55 adoption agencies, including 14 in Mumbai alone.

The Bombay High Court’s ruling last Monday on foster care, a term used for the period the child stays with his prospective parents before the legal formalities are completed, gave an impetus to this ‘family’ cause. Till now, adoptive couples living outside the court’s jurisdiction could not take a child under foster care to their homes. For instance, a couple living in Delhi could take a child from Mumbai with them only after the adoption process was legally complete. In case they want to live with the child before the process was completed, they had to settle down in the city till the child was legally theirs.

Though the HC ruling will impact only a few couples — most agencies say they deal largely with local couples — experts say the ruling will foster greater bonding between prospective parents and the child before the formal handover of the child, and for the agencies, a better understanding of whether the couple and the child suit each other.

“It enables both, the agency and the parents, to confirm that the adoption will work,” says a social worker. Just in case there are any regrets, the agency can always withhold adoption. Foster care has always been understood to facilitate this intelligence, but the geographical limits set for the purpose was considered to be a constraint for parents living outside the court’s jurisdiction.

On the flip side, the order entails some additional pains for the adoption agencies. “This means stretching our resources to keep an eye on the child,” says the trustee of an adoption agency. “It’s an encouraging development for adoption as a whole, but this will add to our burden. We work on shoe-string budgets,” says the administrator of another organisation.

Adoption agencies are usually attached to NGOs, and entitled to receive grants from the government. Some of them, located in remote areas, get money under the Union Women and Child Development Ministry’s Shishu Graha scheme, to encourage in-country adoption. Agencies, though, complain of delays in disbursement. “The money usually doesn’t come on time,” says the administrator. Over the years, the law has been firmed up to refine the adoption process. The apex court order is the latest in this regard. However, what stands out sorely in an otherwise fault-free legal framework is the absence of a uniform adoption law. As with the uniform civil code, consensus has eluded this much-solicited legislation as well.

So, Hindus, Jains, Sikhs and Buddhists are governed by the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956, which permits adoption of a child of up to 15 years of age while other minorities like Christians, Parsis and Muslims adhere to the Guardians and Wards Act (GWA), 1890, which permits adoption of a child till he turns 18. While the Hindu Act is more or less fine (see box), the other Act is not.

The biggest complaint as far as the law goes is the ban on adopting a child of the same sex. “If a couple has a girl, they cannot adopt a girl again,” says advocate Rakesh Kapoor. “And that is a lacuna that needs to be addressed.” The condition was put in place to prevent discrimination against the girl child even during adoption, but agencies talk of the predicament of couples who are often keen to adopt a girl despite having a girl of their own.

GWA does not bestow automatic inheritance on the child, who remains a ward. The adoptive parents are governed first and foremost by their personal law and can deprive the adopted child of right to their property.

A legal handicap is the absence of any provision to take back a child in the rare event he is ill-treated by his adoptive parents. “Adoption is irrevocable,” points out Ashwini Thatte, senior project coordinator, Vatsalaya Trust. In one case, the child was taken back with the intervention of the Child Welfare Committee - formed by the state government — after counseling failed to make the parents behave.

Not all neglected or abandoned children, though, even have access to getting adopted. Unlike the West, there is little awareness here of foster care — the concept of nurturing a child without any claims on him till he is claimed back by his parent or guardian. It is distinct from foster care, which is for a short period, till adoption renders the child to the parents. Children who are not medically fit to be placed for adoption or children whose parents are not capable of fending for them are candidates for foster care.

However, there is no separate law on the subject. The Juvenile Justice Act deals with the issue, permitting foster care for a child by an individual or an institution. “The development of a foster care programme could help find homes for neglected and delinquent children who land up in depressing government homes,” says Sunil Arora, coordinator of the Bal Asha adoption cell. “They are older, and because of legal issues, can’t be placed for adoption,” he says.

Thatte recounts the experience of trying to find a home for a six-year-old whose mother was mentally challenged. “We moved heaven and earth but found nobody to care for her,’’ she recalls. Finding a foster home is indeed tough. That’s why the centre pitches in with grants to meet the nutritional and medical needs of the child. “Foster families are paid for such children, who can also be placed for adoption in case the parents abandon them,” says Savita Nagpurkar, Project Officer, Indian Association for Promotion of Adoption.

A child under foster care gets no privileges that an adopted child does. “In guardianship, the child doesn’t get rights but can be willed some assets. A child under foster care can make no claims whatsoever on the foster family’s assets,” adds Thatte.

![submenu-img]() 'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case

'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…

Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…![submenu-img]() You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why

You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...

Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…

Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...

Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react

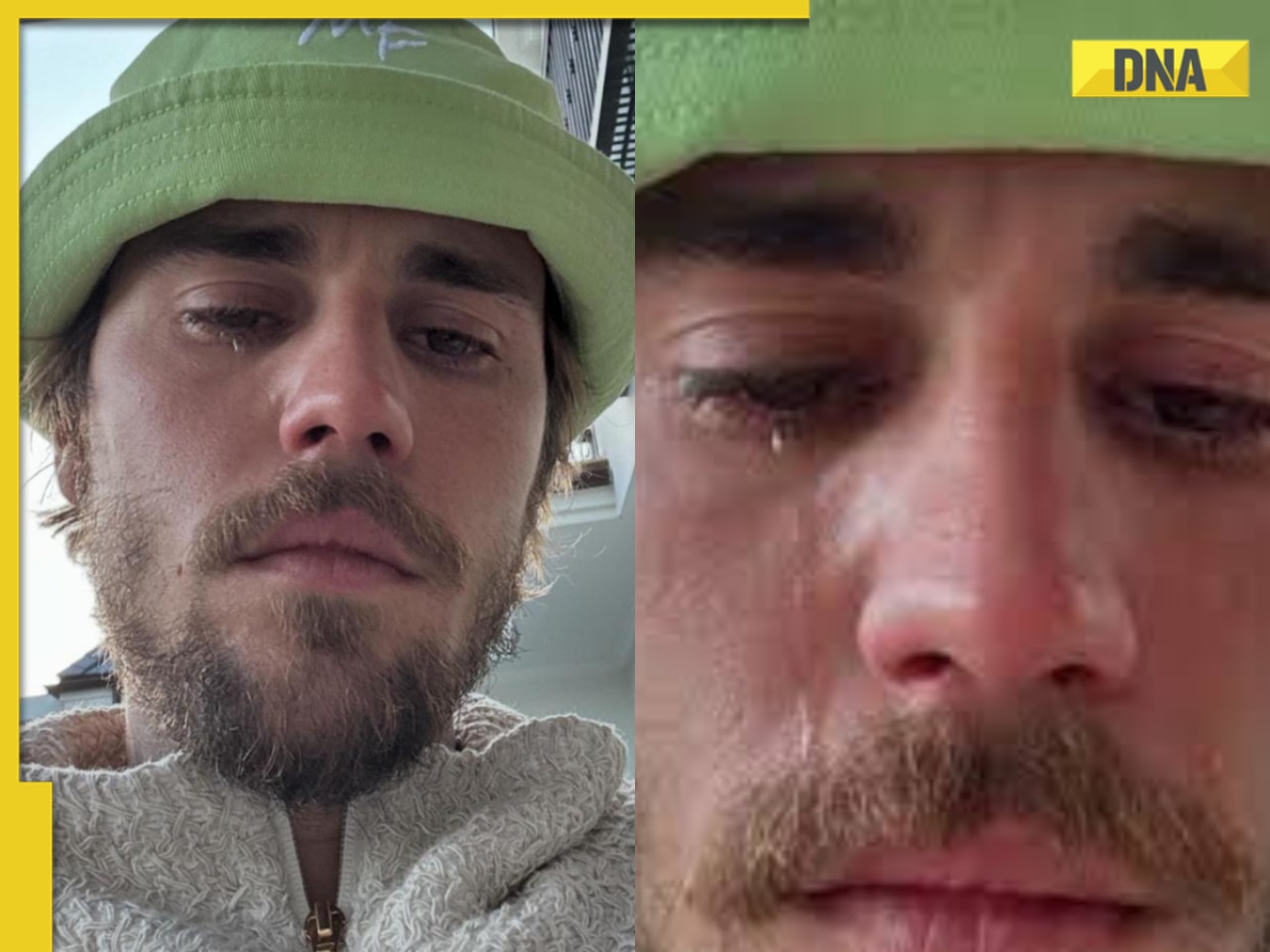

Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react![submenu-img]() This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore

This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore![submenu-img]() This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..

This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..![submenu-img]() Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute

Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad

IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets![submenu-img]() PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup

PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans

IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)