Salil Desai visited the site of the post-World War II Nuremberg Trials and was struck by how peaceful it is today.

At a place of historical importance, you subconsciously look for a specific atmosphere — a sense of the past that has seeped into the walls and clung on for you to touch.

However, the stillness and the small size of courtroom 600 at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, where the war crime trials against the Nazis were held after World War II, leave me disoriented. I don’t know what I expected — an imposing edifice of justice, perhaps, calculated to overawe and unnerve the 21 Nazi leaders who stood trial. But Courtroom 600, which, surprisingly, in functional even today, is no more than the size of a modest banquet hall.

It takes a while to accept that this was the setting of the biggest legal undertaking in history, involving 218 days of proceedings, 1000 personnel, 360 witnesses, 3,00,000 affidavits and documents. At the end of it all, 12 death sentences and 7 terms of life imprisonment were given to the men of the Third Reich.

My eyes skim the wood-paneled interiors and elegant chandeliers to seek points of resemblance with the black and white photographs I had seen in books. I stand a few feet away from where the Nazis must have awaited their fates — Hermann Goering defiant and belligerent, Rudolf Hess cowering and pathetic, Albert Speer contrite and introspective.

Situated in Bavaria, Nuremberg was chosen as the venue for the trials because its Palace of Justice was one of the few complexes that escaped war damage. An undestroyed prison was attached to it, ideal to incarcerate Nazis. However destiny showed a rare penchant for poetic justice. It was here that the Nazis held their spectacular annual party rallies since 1933 and passed the infamous racial laws that sealed the fate of the Jews.

The guide points to a door, crowned by a huge mythological sculpture in granite, just behind the docks of the Nazis. “This door opened into an elevator that brought the prisoners into the courtroom. A tunnel connected the court with that part of the prison where the cells of these top Nazis were located.”

Courtroom 600’s serenity is baffling. How can a place which witnessed a comprehensive exposition of the twisted logic of genocide be free of all those disturbing influences?

“The undertrials were constantly watched,” the guide continues, pointing to a photograph depicting lines of sentries positioned to stare fixedly into prison cells, “Yet Hermann Goering consumed cyanide the night before his execution.” His fellow Nazis were hanged the next day, on October 16, 1946. I now know why Courtroom 600 is tranquil — because true justice was and continues to be done here — one way or the other.

As I step out onto the quiet Bärenschanzstraße, it’s hard to believe Nuremberg was once a bustling city echoing the raucous cries of Aryan chauvinism. Perhaps the burden of its past has turned it into a colourless, listless place, with no signs of the charm one expects from a vintage city founded in the 11th century.

![submenu-img]() 'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case

'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…

Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…![submenu-img]() You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why

You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...

Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…

Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...

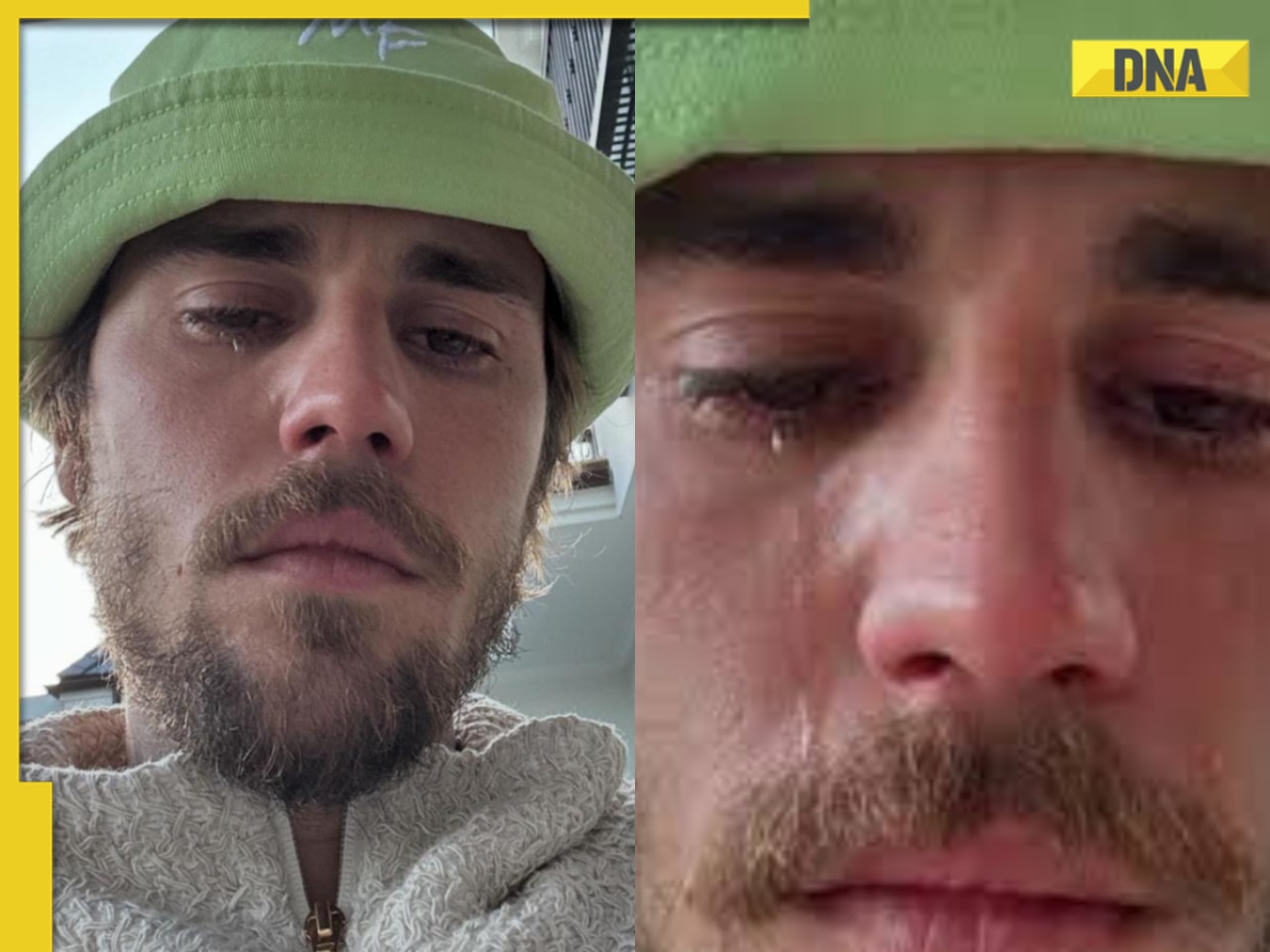

Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react

Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react![submenu-img]() This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore

This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore![submenu-img]() This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..

This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..![submenu-img]() Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute

Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad

IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets![submenu-img]() PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup

PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans

IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)