The best way to establish whether a book is truly funny is the Commuter Guffaw Test, where a piece of writing seduces you into disregarding your surroundings.

The best way to establish whether a book is truly funny is the Commuter Guffaw Test, where a piece of writing seduces you into disregarding your surroundings and

startling your fellow passengers.

After nearly 30 years of literary incarceration, Woody Allen staged a prison break last year with a new collection of short stories titled, appropriately, Mere Anarchy. The book, which hit our local shelves recently, is an intriguing specimen of 20th century humour. Twentieth century, and not the 21st, because the references and even world view, given the author’s vintage, would appear to GenX as somewhat dated.

Having said that, what makes the writing intriguing (and modern, too) is Allen’s exceedingly strange set of choices in subject matter, culled mostly from an eccentric jumble of news items and clippings that he cites at the beginning of each story. In the stories, he writes about futuristic fabrics, prayers sold on eBay, spiritual gurus, and even a short misadventure featuring our favourite moustache-rack, Veerappan. But what exactly is it that qualifies this book as funny? To answer that, one must examine what makes any writing humourous. And as this article is not really a review of Allen’s book, as Allen’s book is merely a McGuffin for our sordid purposes, we may now move onto the crux of the matter: the joke. Do you know how jellyfish commute? No? Wait for it.

The test of a really funny piece of prose is how well it responds to the public transport’s bilious eye. If your light reading for the morning’s commute gets you guffawing like a nitrous oxide salesman — heedless of the many stares, affronted whispers and elbows lodged in your ribs — you can rest assured that what you have in your hands is a piece of A-grade clownery. It is often a misconception that the labels on library racks are efficient signifiers of their contents; the Commuter Guffaw Test is perhaps the only true indicator of a well-timed tickle-bomb; indeed, the most reliable ‘humour section’ is that bus/train seat you just fell off laughing.

Humour, as per leading encyclopedia-makers, is not classified under genre fiction, presumably because good writers of all dispositions must necessarily employ some element of wit in their works. Having said that, there are some among these writers who are funnier by far than others, and there exists a comic elite even among that minority who are so explosively funny as to seduce you into disregarding your surroundings and startling your fellow passengers. Who are these lords and ladies of LOL, you ask? Here is a brief, severely non-comprehensive humour-fiction overview:

Early Days

It all began roughly one-fourth of a millennium back, in 1759, with Tristram Shandy, one of the greatest comic characters ever to... Ah, no, confound it. Let us begin at the beginning. It all began, Eeyore’s years ago in 1605, with Don Quixote, a nutty geriatric given to impassioned daytime hallucinations. If the strength of a work of art is in its premise, The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote Of La Mancha is a tricep-flexing mural-painting windmill among a goggle of illiterate giants. Miguel Cervantes’ picaresque novel, chronicling the misadventures of a childish imagination trapped in an old man’s body, birthed several generations of pretenders and a few worthy heirs.

Chief among the latter was Lawrence Sterne’s hilariously over-technical masterpiece, The Life And Opinions Of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, considered by many to be the greatest comedy novel written in the English language, and also perhaps the first instance of a postmodern literary technique. One of the central conceits of the novel is that it never really seems to begin, owing to the narrator’s propensity to wander off into various tangents at the slightest whimsy.

By the end of the book Shandy has, at considerable length, said everything about everything without really saying anything about anything. It is not hard to imagine an 18th century Londoner, having just read an embarrassing anecdote involving Shandy’s emasculated uncle Toby, falling mirthfully off her horse-drawn carriage.

For Something Different

The idea of wit that gave shape to current day literature, a major revision on the earlier situational humour, owes much to the genius of one Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, the undisputed monarch of the descriptive sentence. By the time of his death in 1975, Plum, as he liked being called, had written nearly a hundred books, every one of them a master-class in creative writing, a body of work that includes novels, plays, short-stories and musicals. His influence on modern writing, humour and otherwise, is immeasurable, evidenced by stylistic echoes in the work of Douglas Adams, Woody Allen, Salman Rushdie and countless others.

Wodehouse’s novels are usually built around farcical, increasingly complex plots involving a rag-tag bunch of characters with peculiar eccentricities. But the real magic of his writing is in imagery so unpredictable, and yet so appropriate (“The drowsy stillness of the afternoon was shattered by what sounded to his strained senses like GK Chesterton falling on a sheet of tin”), that the effect on one’s ulnar nerve is instantaneous. If one were to draw a map of new humour, PG Wodehouse could well be the bright focus, with various comic luminaries, from Roald Dahl to Stephen Fry to Nick Hornby, radiating out from the centre.

This history of sorts, of course, is by no means extensive, as conveniently disclaimed earlier in this article. There are several great names missing from our panorama: American humourists, ranging from Mark Twain to Robert Benchley to that one-man publishing army of the internet age, Dave Eggers; and Indians like the prolific RK Narayan and the opposite-of-prolific, forgotten GV Desani. Oh, and women humourists like Erica Jong, Mae West and our own Manjula Padmanabhan (may their tribe increase), who are more often than not unjustly relegated to the footnotes of humour writing. But my intention was merely to set up the joke. The punchline is in the reading.

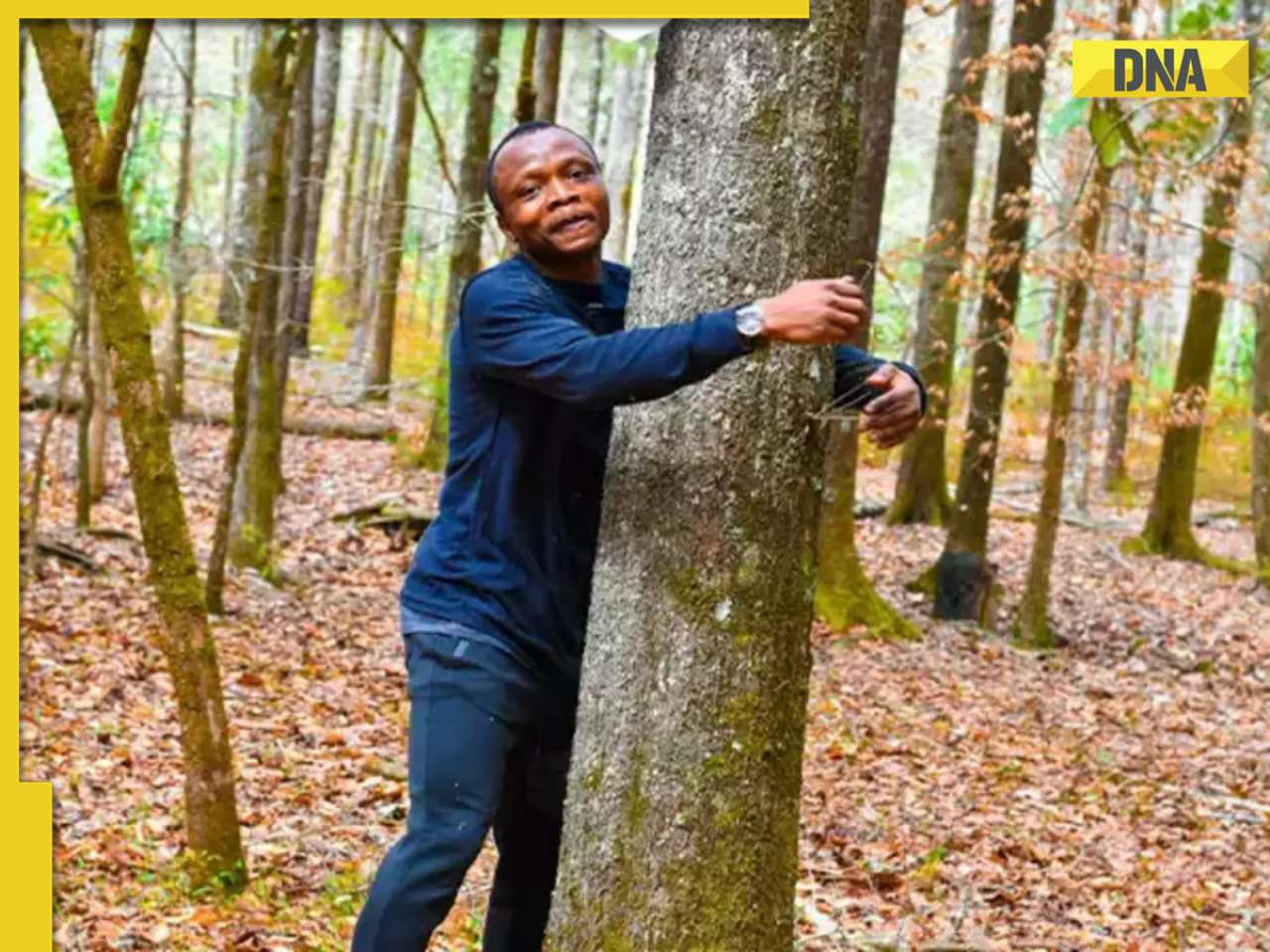

![submenu-img]() Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour

Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour![submenu-img]() This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...

This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...![submenu-img]() Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report

Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report![submenu-img]() Ambani, Adani, Tata will move to Dubai if…: Economist shares insights on inheritance tax

Ambani, Adani, Tata will move to Dubai if…: Economist shares insights on inheritance tax![submenu-img]() Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch

Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’

Alia Bhatt wears elegant saree made by 163 people over 1965 hours to Met Gala 2024, fans call her ‘princess Jasmine’![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...

This actress, who gave blockbusters, starved to look good, fainted at many events; later was found dead at...![submenu-img]() Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report

Taarak Mehta actor Gurucharan Singh operated more than 10 bank accounts: Report![submenu-img]() Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy

Aavesham OTT release: When, where to watch Fahadh Faasil's blockbuster action comedy![submenu-img]() Sonakshi Sinha slams trolls for crticising Heeramandi while praising Bridgerton: ‘Bhansali is selling you a…’

Sonakshi Sinha slams trolls for crticising Heeramandi while praising Bridgerton: ‘Bhansali is selling you a…’![submenu-img]() Sanjeev Jha reveals why he cast Chandan Roy in his upcoming film Tirichh: 'He is just like a rubber' | Exclusive

Sanjeev Jha reveals why he cast Chandan Roy in his upcoming film Tirichh: 'He is just like a rubber' | Exclusive![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Mumbai Indians knocked out after Sunrisers Hyderabad beat Lucknow Super Giants by 10 wickets

IPL 2024: Mumbai Indians knocked out after Sunrisers Hyderabad beat Lucknow Super Giants by 10 wickets![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Punjab Kings vs Royal Challengers Bengaluru

PBKS vs RCB IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Punjab Kings vs Royal Challengers Bengaluru![submenu-img]() Watch: Bangladesh cricketer Shakib Al Hassan grabs fan requesting selfie by his neck, video goes viral

Watch: Bangladesh cricketer Shakib Al Hassan grabs fan requesting selfie by his neck, video goes viral![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Rajasthan Royals by 20 runs

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Rajasthan Royals by 20 runs![submenu-img]() Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour

Viral video: Ghana man smashes world record by hugging over 1,100 trees in just one hour![submenu-img]() Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch

Cargo plane lands without front wheels in terrifying viral video, watch![submenu-img]() Tiger cub mimics its mother in viral video, internet can't help but go aww

Tiger cub mimics its mother in viral video, internet can't help but go aww![submenu-img]() Octopus crawls across dining table in viral video, internet is shocked

Octopus crawls across dining table in viral video, internet is shocked![submenu-img]() This Rs 917 crore high-speed rail bridge took 9 years to build, but it leads nowhere, know why

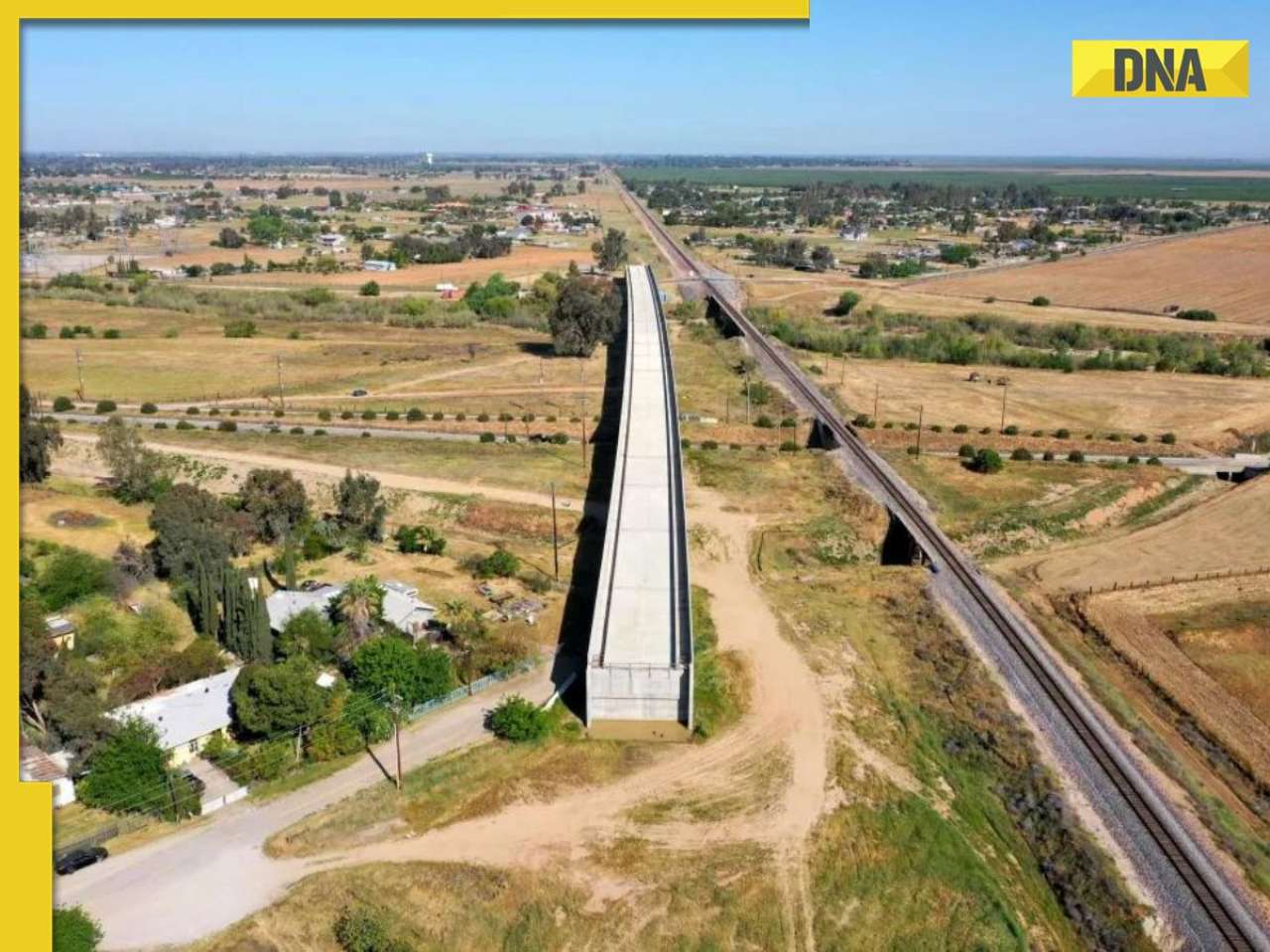

This Rs 917 crore high-speed rail bridge took 9 years to build, but it leads nowhere, know why

)

)

)

)

)

)