It's grown up, wildly complex and full of Yorkshire accents. Yet somehow, 'Game of Thrones' is the fantasy hit of the decade. Craig McLean visits the set.

In the wilds of Westeros, a storm is coming. Following the execution of noble warrior-regent Ned Stark, his son Robb is on the march and out for dynastic revenge. His target: the southern armies of the Lannister family. At his back: The Wall, a 700ft-high, 300-mile-long barrier guarding the kingdom's polar extremities. His mother is elsewhere in the kingdom, busy interrogating a captured incestuous twin. But Robb's bastard brother, the aptly named Jon Snow, has travelled north, the better to keep at bay the monsters thought to lurk deep in the frozen wastes.

In King's Landing, meanwhile, terrible teenager Joffrey Baratheon - imagine a hoodie turned psychotic by a divine right to rule - has taken his father's place on the Iron Throne. But can he withstand his plotting uncle, and the threat posed from across the Narrow Sea by returning queen Daenerys Targaryen and her fire-breathing "children"?

Out in the wilds of Northern Ireland - 29 miles from Belfast, to be precise - another storm is fading. It is late October 2011, and Hurricane Irene recently blew across the province, causing havoc for the many people involved in making season two of Game of Thrones. "It uprooted a great big marquee - the whole f------ thing went up!" marvels Charles Dance, the venerable British actor who plays patriarch Tywin Lannister. "We lost a set. It was last seen heading out towards the Atlantic. We're working in quite a dramatic environment - and it does help. There's something mystical about Celtic environments. It's not like England."

Game of Thrones, the television adaptation of American author George R?R Martin's bestselling, medieval-flavoured novel series A Song of Ice and Fire, is the latest must-watch offering from the American network HBO, the people who gave us The Sopranos, The Wire and Deadwood. Bombarded with critical and commercial hosannas, this saga of warring clans was recommissioned within two days of its debut last spring, and won Peter Dinklage - who plays the devilishly charming dwarf Tyrion Lannister, also known as The Imp - an Emmy. Broadcast in Britain on Sky Atlantic, Game of Thrones is the channel's highest-rated show yet. In the US, each episode was viewed by almost 10 million people.

'Game of Thrones' is fantasy without the fantastical (except for the dragons). Unlike the wizardly weirdness of Tolkien, this drama feels largely mortal underfoot and is pitched at a decidedly adult audience of both men and women.

Set in the Seven Kingdoms of the mythical continent of Westeros and peopled by a huge cast of largely British and Irish actors, of both genders and every age, the pounds 40?million series is filmed in Iceland, Croatia and Morocco. But the bulk of the action is shot in Northern Ireland, a geographical element that makes the series feel more terra firma than other-worldly. This is "genre" television for people who like their escapist drama emotional, earthy, full of political intrigue and brimming with female characters whose "strength" doesn't just come from how good they look in a chain-mail bikini.

All of which explains why, keeping warm between takes in a converted linen mill near the town of Banbridge, Emilia Clarke - the 23-year-old Londoner who plays Daenerys - is able to convincingly hymn the praises of a show that is "gritty in a good, realistic way. It was never meant to be a show for kids." Then, half an hour and one film set away, an actual kid - 14-year-old Maisie Williams, who plays plucky princess Arya Stark - tells me that, yes, she has watched the whole of season one, and that she enjoyed it despite knowing how "the beheadings and things" were shot.

Which is why, in turn, in another Game of Thrones set - located in the old shipyard Paint Hall in Belfast's Titanic Quarter - we stumble upon Ned's head in a shed. The elder Stark (played by Sean Bean) was decapitated by the sinister Lannisters in season one. It was a shocking scene, not least because no one expected a ratings-hungry drama - even one with a huge ensemble cast - to kill off a main character so abruptly.

"Wiser network bosses might have said, 'You can't kill Sean Bean nine episodes into your show!'?" laughs Bryan Cogman, a writer on both seasons. But he thinks that this iconoclastic approach - "guess what, the lead dies!" - taken by the series creators, David Benioff and Dan Weiss, was what appealed to HBO. In fact, the executives who ordered the series had no idea that plot twist was coming until they'd already committed. But there's much more to Game of Thrones than one leading man.

"It took me two days to get the smell off my fingers," recalls Dance. He's talking about a scene in season one in which his character ("he's not a villain; he just wants to maintain the status quo, no matter what") hacks his way round a haunch of venison. It was a real deer, and it required real guts all round (of the deer especially). The film-makers gave him no reason why Tywin Lannister should be such a proficient butcher. But they did furnish the actor with an explanation for the show's profusion of sex.

"I was never a fan of the Tolkien books," says Alan Taylor, director of several episodes. "And partly it's because whenever I'm in that world I feel there's a huge thing missing. It's mythologically very rich and dense but it left out huge portions of life experience - and sex was one of them. The Rings books were atrophied in that category." It's not a charge you could level at Game of Thrones' gung-ho depiction of inter-gender relations. "And it's all doggy fashion!" says Dance gleefully. "They said, 'the missionary position wasn't in fashion in the Seven Kingdoms. We wanted it to be animalistic, Charles.' I said, 'It's certainly that!'?"

Rigorous attention to detail is everything in this series. Given the source books' rabid following, it had to be thus. Brick-thick, 1,000-page hardback novels don't normally fly off the shelves, but Martin's epics often dominate the bestseller lists. In the US, last year's six-years-in-the-writing A Dance With Dragons sold almost 300,000 copies on its first day of publication. Prodigious author though he is, it's often not enough for the disciples: Martin's vast online fan community regularly berate him for not writing the books - five of them so far - fast enough. And, because of his leisurely pace, there's a genuine fear that Martin, who is in his sixties, will die before the series is complete. Fans also pull up the former Hollywood scriptwriter for continuity errors (a horse changing sex, a character's eyes changing colour), which tells you something of the micro-detailed yet macro-scaled vastness of his chronicles. "People are analysing every goddamn line in these books," the author once said. "And if I make a mistake they're going to nail me on it."

The television team are doing their best to "make real" these worlds. Over on the Moroccan and Croatian locations, Iain Glen (playing Ser Jorah Mormont, exiled knight and escort of Daenerys) had to brush up on the horse skills acquired on "maybe 20 previous jobs. You know, horses can make you look silly, or they can flatter you," says the Scots actor last seen playing a joyless newspaper magnate in Downton Abbey. "And we had teething problems, but then they got the right horses under us." The Americans, says Glen, have the luxury of "TV budgets we just don't have in this country". Even so, the producers recently had to beg for more money in order to film something sorely lacking from the first series - an epic battle scene, filmed in a stone quarry over the course of a month. After all, says Benioff, "This season is about a country at war."

Here in Northern Ireland an entire start-up film industry, worth hundreds of millions of pounds to the local economy, has been catalysed by the arrival of the huge Game of Thrones production. A 145-strong construction crew laboured to build the kingly palaces, chambers and courtyards. All told, 700 craftspeople, from armourers to costumiers to experts in medieval sigils, toiled to bring to life Martin's extraordinarily detailed kingdom - inspired largely by War of the Roses-era England - to life.

The television adaptation reflects this. ThMe Stark men, for example, all have Yorkshire accents - even Glaswegian actor Richard adden (who plays Robb Stark). That's because their lord and master was Sheffield-born Bean. Ordinarily, American audiences don't readily embrace such "foreign" ideas. But Game Of Thrones, propelled by the rabid readership fan base - the books have sold over 15?million copies worldwide - bucked the trend. It was attention to the saga's nuts and bolts, recalls Benioff, that won he and his writing partner Weiss the collaborative hand of Martin.

After the success of Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings trilogy, Martin was inundated with offers from Hollywood studios in hot pursuit of the next fantasy franchise.

"Some of them told George, 'Yeah, we've figured out how to make it work as a two-and-a-half-hour movie,' and it always involved cutting out the plot lines. Any feature adaptation would have missed maybe 90 per cent of the story." At their first meeting with Martin, he tested their fealty to his magnum opus. "He asked us a question - 'Who do you think Jon Snow's true parents are?' And it was kind of nerve-racking, because Dan and I both had strong opinions about it. And we thought, 'If we get this wrong, maybe we're not gonna get this job.' Luckily, we got it right, so that helped." Martin responded enthusiastically to the idea of a sequence of 10-episode series, each corresponding (roughly) to one of his books. "And luckily it turned out he was a great fan of HBO - he knew they had done shows like Rome and Deadwood." Alan Taylor worked on the latter show, and on other HBO hits such as Six Feet Under and a certain saga of ordinary Mafia folk. Better than anyone he can vouchsafe the accuracy of Game of Thrones' unofficial subtitle: The Sopranos in Middle Earth.

"I think it's accurate in that HBO has always been very, very good at a very specific thing," replies the director, "which is to take an audience to a world that was tantalising and thrilling and foreign and exciting - and then surprise us by how intimately we connect to that world. That was certainly true with The Sopranos, where we got to go into the Mob world in a way that had never been done before. But there was some nervousness about whether we could do a fantasy show and really find millions [of viewers] that went beyond the usual fantasy community." Of course, in the post-Twilight, post-Potter, mid-Hunger Games and pre-Hobbit world, certainly that community is growing all the time.

"I hear it all the time: people who say they were surprised that they had never really connected to a fantasy story before, and didn't consider themselves that kind of audience - but found themselves drawn in by this one."

Richard Madden's character Robb, the princely son of Ned, is forced to step up in season two. This morning, back in Belfast's Titanic Quarter, Madden went to meet his director. They rendezvoused in the Red Keep, home of the titular, much-coveted, much-disputed seat of rulers. The Iron Throne - which drew crowds when it travelled to London last year for the publication of A Dance With Dragons - is forged from the swords of lords who have bowed before the king. Did the actor dare sit on it? He grimaces, before displaying a loyalty to the books that would make Martin proud. "I walked round it but I was thinking: I can't sit on it. I'm not allowed to. Because Robb can't quite sit on it yet. So I've touched it and looked at it and taken pictures of it on my iPhone. But I've not sat on it. I couldn't let myself." That, perhaps, is a treat for season three.

![submenu-img]() 'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case

'He used to call women to...': Woman shares ordeal in Prajwal Revanna alleged 'sex scandal' case![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…

Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…![submenu-img]() You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why

You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...

Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…

Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...

Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react

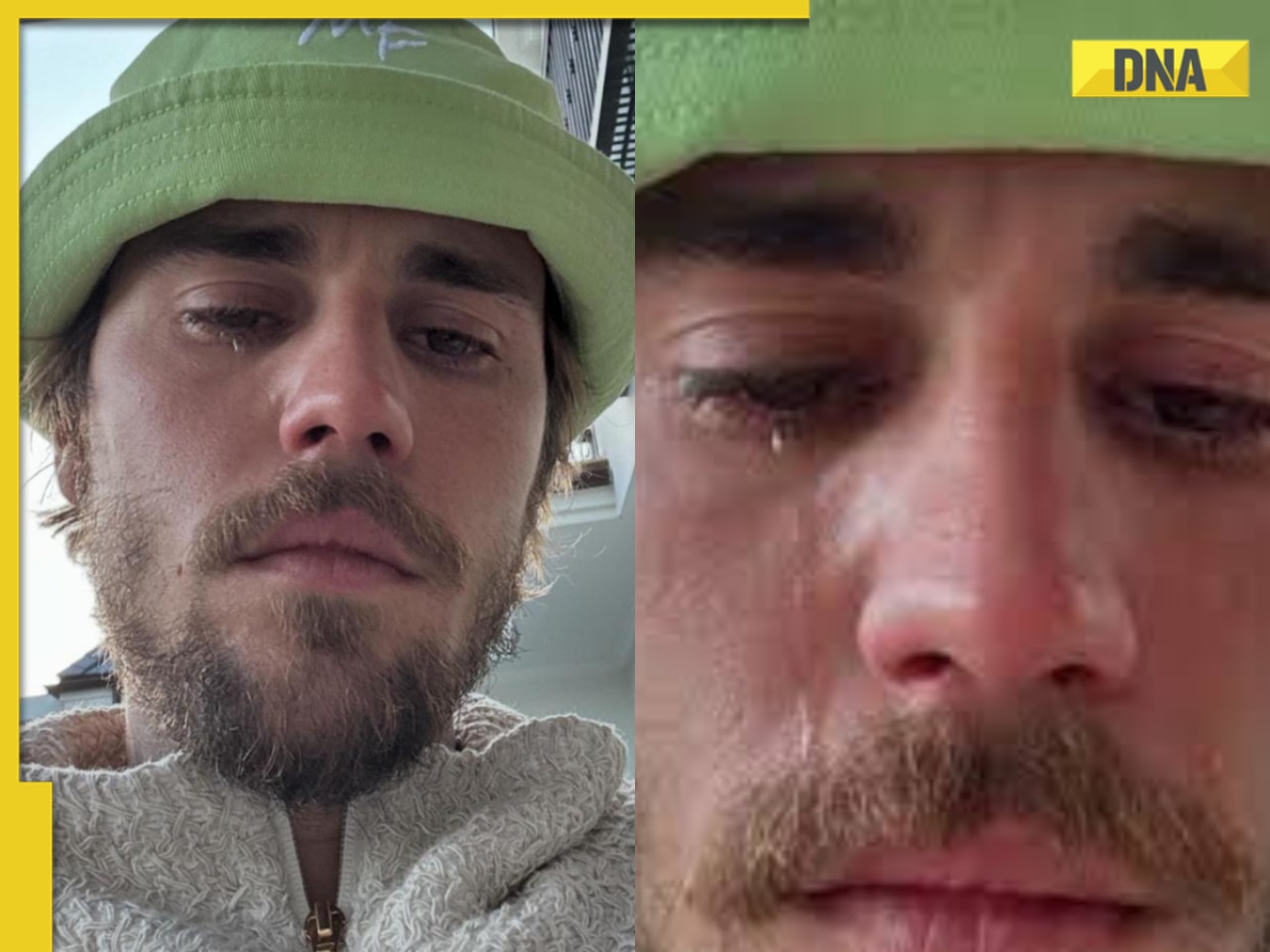

Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react![submenu-img]() This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore

This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore![submenu-img]() This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..

This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..![submenu-img]() Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute

Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad

IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets![submenu-img]() PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup

PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans

IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)