His picture adorns currency notes and he is hailed officially for fighting Japanese invaders and unifying China.

Leaning on a cane, Wang Bin hobbled out between the columns of the mausoleum on Tiananmen Square that houses the embalmed body of Mao Zedong, happy he had the strength to visit the shrine before he died.

"Chairman Mao liberated the poor and miserable people. He showed us the road to happiness," said Wang, 87, a wisp of a man with dark wrinkled skin, a thin white goatee and nearly toothless grin who hails from Hohhot, the capital of Inner Mongolia.

"I wanted to see Mao Zedong before I die."

Friday is the 35th anniversary of the death of Mao, a charismatic leader once deified by all and still idolised by many. His picture adorns currency notes and he is hailed officially for fighting Japanese invaders and unifying China under Communist Party rule.

But even the party has condemned as mistakes the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution which sought to unify the nation and transform economic and political thought through brutal adherence to Mao's version of communism.

Still, tens of thousands of others this week joined Wang at the mausoleum, though Friday's milestone is passing largely unnoticed by most of the 1.34 billion Chinese too busy trying to make money, and, increasingly, spend it.

It is a far cry from Sept. 9, 1976, when the reign of the leader known as the Great Helmsman ended with his death.

I had come to China for the first time three days earlier as a teen-ager with my mother, a native ethnic Chinese, to meet my 81-year-old grandfather. He had moved south from Beijing in the 1930s to set up the family's traditional Chinese medicine business in Nanjing and Shanghai.

I marvelled at the teeming streets, the hole-in-the-wall enterprises and the overwhelming use of bicycles for transportation.

Mao Zedong at the time was a virtual god to the populace. I was struck by the spirited and ubiquitous Cultural Revolution posters and slogans, many written on cracked blackboards with coloured chalk.

"He was a colossal person who stood above the rest of the people, who was very intimidating to virtually everybody," says Arthur Rosenbaum, a professor of Chinese history at Claremont McKenna College in the United States, currently doing research in Beijing.

"He's also seen by many as the person who stood up for China."

My mother hadn't seen her father for 27 years, the family kept apart by war with the Japanese, civil war, and the establishment of the People's Republic and its sudden isolation from most of the West, where my mother had gone to study.

Around lunchtime on Sept. 9, broadcasts on the radio and on public speakers instructed people to listen to an important announcement at4pm.

Then: Mao had died at 10 minutes after midnight that morning. Instantly society ground to a halt. Schools and parks shut, and theatres were hurriedly turned into places of mourning.

Within hours everyone had a black armband, including me.

Television showed long lines of people weeping and distraught. In Shanghai I saw the waiting, but no wailing, as citizens in drab outfits queued quietly, their faces subdued or dazed.

Mao's passing created alarming uncertainties. My mother explained in a low voice the fear of an attack from the Soviet Union during Mao's funeral.

During the service on Sept. 18, guests at Shanghai's Overseas Chinese Hotel watched it live. I looked out the window and sure enough on the street 10 floors below were stationed volunteer "Shanghai Minbing" (Shanghai People's Militia) every few meters.

A In the 35 years since Mao's death, China has cast away the dogma of class struggle and the rule of the proletariat. Mao's image is largely paternal and benevolent.

"I think the Chinese Communist Party's propaganda has worked," says Mao Yushi, a retired economist in his 80s and a vocal critic of the Maoist era and of the party.

"They cover things up and don't let people know a lot of the bad things," said Mao Yushi. "Only a few people know the truth about Mao Zedong."

Historians agree that Mao's biggest campaigns were his biggest mistakes. The 1958-61 "Great Leap Forward" was such an ill-conceived attempt at breakneck modernisation that it caused the starvation deaths of tens of millions. The 1966-76 Cultural Revolution was a decade of violent class struggle that robbed the country of a generation of educated students.

"How many people died from your political mistakes?" economist Mao Yushi said. "By this standard, 50 million died in Mao Zedong's era, which is more deaths caused by any other political party's rule in the world."

To other Chinese, the legacy of Mao varies.

"How you stand on Maoism depends on where you sit at the table," says Richard Baum, a China expert at the University of California Los Angeles and author of the book, "Burying Mao."

"I think those who haven't been treated so kindly under the reforms are likely to be more nostalgic than those who are doing just fine," Baum said in an interview from France. "You can gauge people's attitudes toward Mao by their recent well-being."

Nowhere is that fondness more evident than at the Mao memorial, which an average 30,000 people visit daily, most of them Chinese.

Mao lies in a crystal coffin in a glass-walled room. Two People's Liberation Army honor guards stand at attention. A few aides in white gloves urge people to move through quickly.

"It's nostalgic. I personally have fond feelings for Mao Zedong," said Fu Guoheng, 55, who trades in fertilizer and visited the memorial this week from the southern city of Ningbo.

"Objectively, Mao was 70 percent right and 30 percent wrong," said Fu, echoing the government's official assessment of Mao after decades of do-no-wrong appraisal.

Outside the memorial hall, souvenir stalls hawk pins, pens, plaques and plates, bookmarks, necklaces and bracelets - all with a Mao image on the front or back.

There are wristwatches with the slogans "Serve the People" or "Long March." A miniature bronze Mao statue goes for 598 yuan ($93.53). A Chairman Mao combination keychain and fingernail clipper is 25 yuan.

Women like the faux jade necklaces with the Chairman's likeness, said one twenty-something sales clerk.

"Everyone feels they have to come here when they visit Beijing," she said, not wanting her name used. Asked if she herself had any special sentiment for Mao, she cocked her head.

"Nope," she said. "But I have to eat, so I need this job."

Visiting the mausoleum and Tiananmen Square this week, I'm struck by the prosperity and choices that urban Chinese have today, compared with my visits to China in 1976 and throughout the 1980s.

This couldn't have happened by sticking to the Maoist way.

"Look, everybody makes mistakes," said Fu, the businessman from Ningbo. "If you didn't, you''d be a god, right?"

![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…

Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man with over Rs 9603670000000 net worth, invites Pakistanis for…![submenu-img]() You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why

You won't be able to board these trains from New Delhi Railway station, here's why![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...

Meet IAS officer who is IIM grad, left bank job to crack UPSC exam, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…

Meet man, gets more than Rs 300 crore salary, accused of killing Google Search, he left Yahoo to…![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...

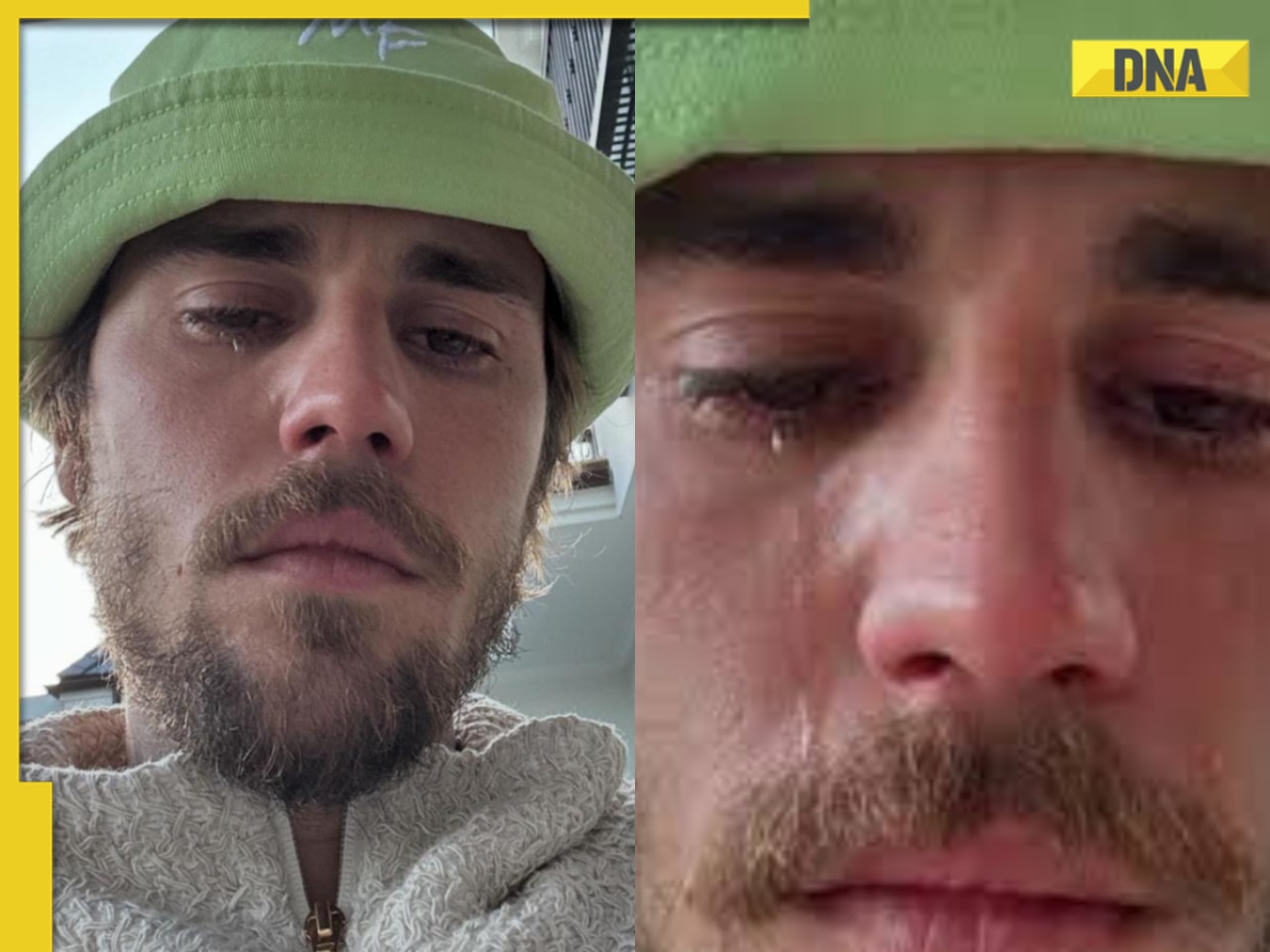

Meet actor, wasted 20 years in alcohol addiction, lost blockbuster to Salman, cult classic saved career at 49, now he...![submenu-img]() Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react

Justin Bieber breaks down in tears amid rumours of split with wife Hailey in new pictures; concerned fans react![submenu-img]() This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore

This film on AI had 'bizarre' orgasm scene, angry hero walked out, heroine got panic attacks, film grossed Rs 320 crore![submenu-img]() This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..

This actor was only competition to Amitabh; bigger than Kapoors, Khans; quit films at peak to become sanyasi, died in..![submenu-img]() Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute

Meet actress who had no money for food, saw failed marriage, faced death due to illness, now charges Rs 1 crore a minute![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad

IPL 2024: Ruturaj Gaikwad, Tushar Deshpande power Chennai Super Kings to 78-run win over Sunrisers Hyderabad![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Royal Challengers Bengaluru beat GT by 9 wickets![submenu-img]() PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup

PCB appoints Gary Kirsten and Jason Gillespie as head coaches ahead of T20 World Cup![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans

IPL 2024: Will Jacks, Virat Kohli power Royal Challengers Bengaluru to big win against Gujarat Titans![submenu-img]() DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)