China’s growing assertiveness now faces pushback from around the world.

China’s increasing exertion of “raw power” on the world stage, and its heavyhanded challenge to an open and liberal international political system will face serious resistance and pushbacks from around the world, say analysts and experts.

Google’s threat to leave China rather than be complicit any longer in censoring the internet may be the most emphatic sign that the threshold of international corporate and governmental tolerance for China’s bending of the rules of conduct has been crossed.

“As China gets more powerful, it will face pushback from the rest of the world,” John Lee of the Centre for Independent Studies in Sydney, told DNA Sunday. “The advances China has made so far in gaining acceptance in the region and in the world will be a lot harder to replicate.”

Much of the criticism that China draws revolves around one theme, says Lee. “China wants to benefit and be a great power within the international system, but it wants to be a free rider: it is not prepared to exercise public leadership, and is only looking to advance its own interests.”

That mindset is manifest across issues: its currency manipulation to protect its exports at the expense of other countries, its unwillingness to commit to internationally verifiable cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, its mollycoddling of disgraced authoritarian regimes in Africa and elsewhere in exchange for access to raw materials and resources, and many others.

“The common thread that runs through these is that China is not willing to bind itself to agreed rules of behaviour,” says Lee.

Steven M Dickinson, an international lawyer with boutique international law firm Harris & Moure, too sees a disquieting change in China’s attitude towards the rules of international trade. “China has begun to believe that it is the dominant power in the world, and that others have to comply with its demands,” Dickinson told DNA on the phone from Qingdao in eastern China.

“China’s approach is this: ‘If world trade law adds advantage to us, we’ll abide by it. But if world trade law restricts us, we’ll simply ignore it’,” he notes.

Dickinson cites a recent case before the World Trade Organisation that, to his mind, reflects this approach. After the WTO ruled against China’s restrictions on media imports from the US and Europe, China’s response was to wilfully ignore it. The attitude, he says, was: “Sure, we lost, but we aren’t going to change anything. You need us, we don’t need you.”

Additionally, he points out, “a lot of the laws that were passed in China at the time of its entry into the WTO, which were intended to allow market access to foreign companies, are now being undermined or pulled back on.” And China is enacting new laws that are “in conflict with its obligations under WTO laws and are designed to increase either the control of the Chinese government or the advantages of domestic Chinese industries.”

In Dickinson’s estimation, while foreign companies looking for a piece of the Chinese market action may increasingly have to abide by “the Chinese way”, China itself could “face pushbacks… on the international stage.”

The risk to China, he points out, is that other countries around the world could well impose punitive tariffs on China-made goods since it had “not been playing by the rules.” And if China wants to acquire companies or assets overseas, it could run into a similar Great Wall of Resistance.

China’s economic rise also draws unflattering attention to one aspect on which it is out of step with the international liberal world order, says Arvind Ganesan, director of the business and human rights project at Human Rights Watch. “Of the world’s five largest economies today, China is the only one that isn’t a democracy,” he told DNA Sunday on the phone from Geneva.

And as Google’s dramatic announcement last week accentuated, China is the only major economy that takes “a very regressive approach to freedom of expression” and “jails political dissidents for what they post online in terms of basic criticism of government policy of the moment.”

Under those circumstances, reasons Ganesan, it’s easy to understand why China will face unsavoury attention and pushbacks. “It’s inevitable that the conduct of the Chinese government and Chinese companies, both at home and abroad, will be scrutinised.”

In many parts of developing Asia and Africa, that kind of scrutiny has given rise to a chorus of criticism of Chinese muscle-flexing. Just as India has in recent months faced several instances of border transgressions by Chinese troops and hectoring by Chinese officials, other countries in East Asia and Southeast Asia have seen the shadow of a rising China fall across their territory.

“China is probably the only ‘dissatisfied’ great power in the international system right now,” says Lee.

“By that I mean: China still has land-based territorial disputes with India and Russia (although in the latter case, they’ve been pacified), and maritime border disputes with Japan and a number of Southeast Asian countries arising from China’s claims over the South China Sea.”

China is also a very “lonely country,” reasons Lee. “I don’t mean that in a judgemental way, but merely as a statement of fact: it has no genuine allies to speak of except North Korea and Myanmar.”

Even its ties with Russia, Pakistan and a few Central Asian countries are “very shallow, based only on very pragmatic, arms-length relationships - as opposed to robust alliances.”

And while China makes much of its developmental aid “with no strings attached” to Africa, there’s been a backlash of sorts - even from African leaders - for its cynical support for corrupt and repressive regimes in return for exclusive access to raw materials and oil resources.

Late last year, Libyan foreign minister Musa Kusa went so far as to liken China’s presence in Africa to an “invasion of the continent” and to “colonialism”. Similarly, an independent Egyptian MP noted that it wasn’t just Chinese scientists and engineers that were coming to Africa, but farmers too, which he said reeked of “neo-colonialism.”

Lee points out that in 2009, Chinese assertiveness wasmost manifest in the first few months, when the US economic crisis was at its severest. “China was openly critical of America, its system and its leadership. But later in the year, when the US economy appeared to revive, the Chinese went back into their shell again.”

The big lesson from this, he adds, is that China “still does only as much as it thinks it can.” To him, it offers a clue to how China might conduct itself in the year ahead. “If the US economic recovery continues, we might see a fairly defensive China, but if the US goes into a double-dip, we could well see a more assertive China.”

![submenu-img]() Anant Raj Ventures into tier 2 and tier 3 cities, pioneering growth in India’s real estate sector

Anant Raj Ventures into tier 2 and tier 3 cities, pioneering growth in India’s real estate sector![submenu-img]() Sophie Turner reveals she wanted to terminate her first pregnancy with Joe Jonas: 'Didn't know if I wanted...'

Sophie Turner reveals she wanted to terminate her first pregnancy with Joe Jonas: 'Didn't know if I wanted...'![submenu-img]() Meet outsider who was given no money for first film, battled depression, now charges Rs 20 crore per film

Meet outsider who was given no money for first film, battled depression, now charges Rs 20 crore per film![submenu-img]() This is owner of most land in India, owns land in every state, total value is Rs...

This is owner of most land in India, owns land in every state, total value is Rs...![submenu-img]() Meet man who built Rs 39832 crore company after quitting high-paying job, his net worth is..

Meet man who built Rs 39832 crore company after quitting high-paying job, his net worth is..![submenu-img]() Meet woman who first worked at TCS, then left SBI job, cracked UPSC exam with AIR...

Meet woman who first worked at TCS, then left SBI job, cracked UPSC exam with AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet engineer, IIT grad who left lucrative job to crack UPSC in 1st attempt, became IAS, married to an IAS, got AIR...

Meet engineer, IIT grad who left lucrative job to crack UPSC in 1st attempt, became IAS, married to an IAS, got AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet Indian woman who after completing engineering directly got job at Amazon, then Google, Microsoft by using just...

Meet Indian woman who after completing engineering directly got job at Amazon, then Google, Microsoft by using just...![submenu-img]() Meet man who is 47, aspires to crack UPSC, has taken 73 Prelims, 43 Mains, Vikas Divyakirti is his...

Meet man who is 47, aspires to crack UPSC, has taken 73 Prelims, 43 Mains, Vikas Divyakirti is his...![submenu-img]() IIT graduate gets job with Rs 100 crore salary package, fired within a year, he is now working as…

IIT graduate gets job with Rs 100 crore salary package, fired within a year, he is now working as…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Taarak Mehta Ka Ooltah Chashmah actress Deepti Sadhwani dazzles in orange at Cannes debut, sets new record

In pics: Taarak Mehta Ka Ooltah Chashmah actress Deepti Sadhwani dazzles in orange at Cannes debut, sets new record![submenu-img]() Ananya Panday stuns in unseen bikini pictures in first post amid breakup reports, fans call it 'Aditya Roy Kapur's loss'

Ananya Panday stuns in unseen bikini pictures in first post amid breakup reports, fans call it 'Aditya Roy Kapur's loss'![submenu-img]() Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...

Remember Harsh Lunia? Just Mohabbat child star, here's how former actor looks now, his wife is Bollywood's popular...![submenu-img]() Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses

Mother's Day 2024: Bollywood supermoms who balance motherhood, acting, and run multi-crore businesses![submenu-img]() Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...

Rocky Aur Rani's Golu aka Anjali Anand shocks fans with drastic weight loss without gym, says fitness secret is...![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Sophie Turner reveals she wanted to terminate her first pregnancy with Joe Jonas: 'Didn't know if I wanted...'

Sophie Turner reveals she wanted to terminate her first pregnancy with Joe Jonas: 'Didn't know if I wanted...'![submenu-img]() Meet outsider who was given no money for first film, battled depression, now charges Rs 20 crore per film

Meet outsider who was given no money for first film, battled depression, now charges Rs 20 crore per film![submenu-img]() Meet actress who quit high-paying job for films, director replaced her with star kid, had no money, now lives in...

Meet actress who quit high-paying job for films, director replaced her with star kid, had no money, now lives in...![submenu-img]() This star kid's last 3 films lost Rs 5000000000 at box office, has no solo hit in 5 years, now has lost four films to...

This star kid's last 3 films lost Rs 5000000000 at box office, has no solo hit in 5 years, now has lost four films to...![submenu-img]() Meet actress viral for just walking on screen, belongs to royal family, has no solo hit in 15 years, but still is…

Meet actress viral for just walking on screen, belongs to royal family, has no solo hit in 15 years, but still is…![submenu-img]() This is owner of most land in India, owns land in every state, total value is Rs...

This is owner of most land in India, owns land in every state, total value is Rs...![submenu-img]() Blinkit now gives free dhaniya with veggie orders, thanks to Mumbai mom

Blinkit now gives free dhaniya with veggie orders, thanks to Mumbai mom![submenu-img]() Meet man, an Indian who entered NASA's Hall of Fame by hacking, earlier worked on Apple's...

Meet man, an Indian who entered NASA's Hall of Fame by hacking, earlier worked on Apple's...![submenu-img]() 14 majestic lions cross highway in Gujarat's Amreli, video goes viral

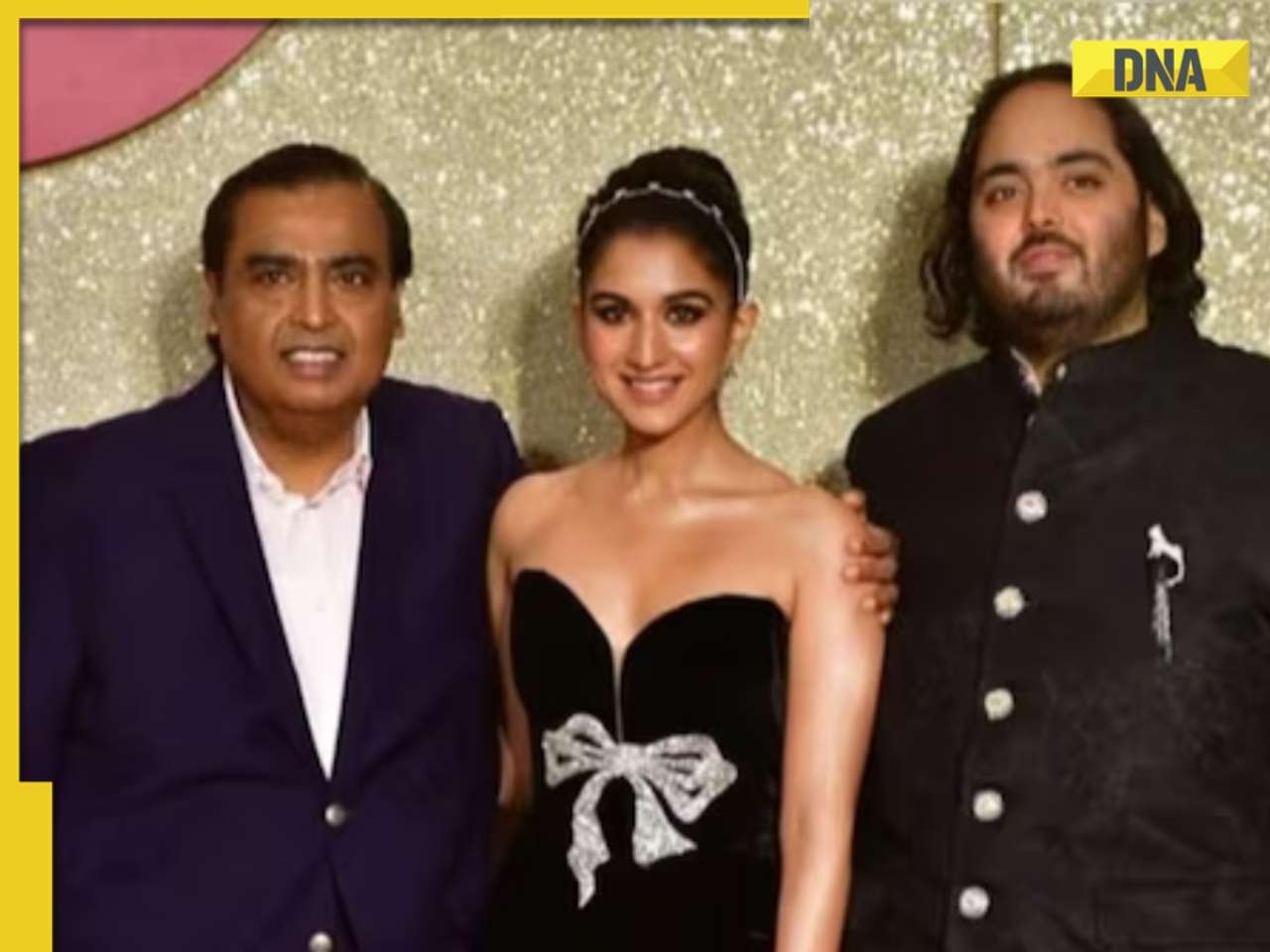

14 majestic lions cross highway in Gujarat's Amreli, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Here's why Isha Ambani was not present during Met Gala 2024 red carpet

Here's why Isha Ambani was not present during Met Gala 2024 red carpet

)

)

)

)

)

)