What happens to the others when one member of a family takes up the gun? DNA reports from the Kashmir Valley.

What happens to the others when one member of a family takes up the gun? DNA reports from the Kashmir Valley.

During 17 years of strife, from 1990 to 2007, more than 20,000 militants were killed in Jammu and Kashmir. According to Kuldeep Khoda, director general of police, there are at least 800 of them currently operating in the state. But there is only so much that numbers can convey. They don’t explain, for instance, what turns a Kashmiri teenager into a militant. Nor do they tell us about the price that mothers, daughters and wives pay when their loved one decides to embrace the gun.

We meet here three women whose lives were torn asunder when a male family member dropped out of civilian life, as it were, and never came back.

‘My son would not listen to me’

When Taja Ahmad Dar heard about her son’s death, she felt relieved. A strange emotion, most people would say, for a bereaved mother. No, Taja did not hate her son. She loved him, and felt the pain of her loss as keenly as any mother would — her son was only 35 when he died. Yet, the answer to why Taja’s grief was stained with relief is the story of what life is like for the families of militants in Jammu and Kashmir.

The Dars are a family of carper weavers from the Panzgam village of Pulwama district in south Kashmir. Since 1993, not once have Taja’s family had dinner together. Her daughter never spent nights at home. Nightfall always brought with it the fear of knocks on the door at midnight. The pall of terror under which Taja’s family had been living for 15 years lifted finally on December 17, 2008 when her son Rayees Ahmad Dar alias Rayees Kachroo, a militant commander of the Hizbul-Mujahideen, was killed in an encounter by security forces.

“I remember the day my son [Rayees] left home. On that day, the security forces had summoned several village boys to their camp for verification. Some boys came back from the camp with beatings. My son fled the village that day,” recalls Taja.

For eight months, Rayees’ whereabouts were not known. People assumed he must have joined the militants. And from that day, the family had to face the grilling of the security forces.

“I went from village to village looking for my son, but I couldn’t trace him,” remembers Taja. “I used to wait at bus stops for hours, looking out for him.”

Suddenly, one night, after eight months, there was a knock and he stood at her doorstep. “The first thing I told him was that the path he had chosen will only lead him to his death. He wouldn’t listen to me,” says Taja.

From time to time, Rayees would land up in the dead of the night “just to say salaam. In all these 15 years, he could never even have a cup of tea with us, let alone stay for a while,” says Taja.

When he was 13, and in class VII, poverty forced Rayees to drop out of school and take up carpet-weaving. His two brothers had already started weaving carpets to sustain the family of six.

“We did not have the money to continue his schooling. But he was a very clever and God-fearing son. He prayed five times a day, kept his fast, read the Quran. Until he became a militant, nobody had ever complained about him,” says Ghulam Hassan, Rayees’ father.

Such was Rayees’ image in the family that they did not suspect anything initially. “Sometimes he would tell us he was going to the orchard to have a look at the fresh apple crop. Or he would say that he was going to play with his friends.” It was later, when his disappearances became more frequent and mysterious, that they began to sense something was wrong. “We kept advising him not to take any rash step. But he would brush it off,” recalls Taja.

But what was it that drove Rayees into the arms of the militants in the first place? His family believes it was religious influence. “We remember it was after he came out of the mosque after Athikaf [ten days of solitary prayers during Ramzan] that he changed. Within days he disappeared from home,” say Taja.

What followed were years of trauma for the family. Finally, early last year, the Dars heaved a sigh of relief when Rayees was arrested. But to their horror, he escaped from the court where he’d been taken for a hearing.

“The night after his escape, I heard a knock at my door.” But it wasn’t the midnight raid she had been dreading. “I opened the door and saw my son.” Fear gave way to rage. “Rayees’ father angrily asked him why he fled from custody. He answered politely that he was not made for jail. He went away.” Taja never saw him alive after that night.

Now, the Dars no longer worry about being summoned to the nearby security camp. No more midnight knocks. But does Taja miss her prodigal son? That is one question to which she has no answer.

‘I thought my son was training to be a policeman’

Sixty-year-old Raja Begum lives just 40 km away from the Dars, in Srinagar’s Abi Guzar area. She still hasn’t come to terms with the death of her two sons at the hands of security forces 17 years ago. One was 25, and the other, 17.

Her elder son, Mohammad Sharief Mir, was a cop before he deserted the police force and fled to Pakistan for arms training. “Sharief had studied up to class XI and had left for Udhampur to undergo police training. All along we were thinking that he was at the police academy. Only later we came to know he had gone to Pakistan,” recalls Raja.

One year after he disappeared, Sharief returned home as a militant of Al Umar Mujhadeen. “My late husband and I tried very hard to convince him to leave militancy, but it was no use. After that he hardly ever kept in touch,” says Raja.

Sharief’s brother Yaqoob was an autorickshaw driver. “Our neighbours informed us that Yaqoob was mixing with militants. But he would deny it outright whenever we asked him about it. He left home one day, and was killed near Barbarshah. Just 21 days later, while we were still mourning his death, we got the news that his elder brother Sharief had been killed,” says Zareena, their sister.

Life has been hard for the family. Raja’s husband died of a heart ailment. Her only surviving son abandoned her to live separately with his own family. “I lost everything,” says Raja.

‘I went from jail to jail looking for my husband’

Tahira Tariq, 34, is what they call a half widow — a rather crude term used to describe women whose husbands have gone missing, and are therefore suspected to be militants. On most days you can see her at the knitting and tailoring centre for the kin of missing people. It’s just a small room with discoloured walls, and a solitary bulb. Tahira sits knitting in the dim light, lost in thought. She’s been trying to eke out a living ever since her husband, Tariq Ahmad, a mason from Boniyar-Uri, disappeared in December 2002. He left for Delhi to meet his employers about a new job. Tahira and her three sons did not know they would never see him again. Days turned into weeks, and there was no word from her husband. Tahira filed a police complaint, and continues to follow it up, while trying to get on with life. “It has been a painful experience for a mother like me with three children to feed. I have sold everything, including all my gold jewellry. I went from jail to jail, camp to camp, to find out about my husband,” she says, her eyes welling up.

Tahira had a Bollywood style marriage with Tariq - she fell in love with him and married him when she was 16, against the wishes of Tariq’s parents.

Things turned ugly after her husband’s disappearance when her in-laws started interfering in the lives of her kids. “One morning when my son was on his way to school, he was intercepted by one of his uncles. This uncle told him to stop studying and do some work instead. I decided, come what may, I will give my kids an education,” recalls Tahira.

She admitted two of her kids in an orphanage in Srinagar. One of the sons has returned after completing his matriculation. She now lives in Srinagar with two of her sons.

The 34-year-old Tahira has not given up her quest for her husband. It has become a monthly ritual for her to join the sit-in in a local park alongside families of disappeared people

According to the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), a human rights body, thousands of people have disappeared without a trace in Kashmir from 1990. According to APDP, there are 18 graveyards, with 1000 nameless graves, in three tehsils of Baramulla district alone.

The security forces deny such allegations. “We do not believe in ‘disappearing’ men in custody. People are saying things without any concrete evidence,” says Colonel DK Kachari, an army spokesman.

![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: 17 cars gutted as fire erupts at parking lot in Delhi

Watch viral video: 17 cars gutted as fire erupts at parking lot in Delhi![submenu-img]() Explained: Why MS Dhoni cannot apply for India head coach job

Explained: Why MS Dhoni cannot apply for India head coach job![submenu-img]() Nargis, Bina Rai, Suraiya rejected this role, chosen actress refused Filmfare Award, film became classic, is based on...

Nargis, Bina Rai, Suraiya rejected this role, chosen actress refused Filmfare Award, film became classic, is based on...![submenu-img]() Delhi hits 52.3 degrees, highest-ever temperature recorded in....

Delhi hits 52.3 degrees, highest-ever temperature recorded in....![submenu-img]() Bihar heat wave: 50 students faint in Sheikhpura due to high temperature, rushed to hospital

Bihar heat wave: 50 students faint in Sheikhpura due to high temperature, rushed to hospital![submenu-img]() RBSE 10th Result 2024: Rajasthan Board Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here

RBSE 10th Result 2024: Rajasthan Board Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who founded India's first pharma company, he is called 'Father of...

Meet Indian genius who founded India's first pharma company, he is called 'Father of...![submenu-img]() DU Admission 2024: Delhi University launches admission portal to 71000 UG seats; check details

DU Admission 2024: Delhi University launches admission portal to 71000 UG seats; check details![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer, who became UPSC topper in 1st attempt, sister is also IAS officer, mother cracked UPSC exam, she is...

Meet IAS officer, who became UPSC topper in 1st attempt, sister is also IAS officer, mother cracked UPSC exam, she is...![submenu-img]() Meet student who cleared JEE Advanced with AIR 1, went to IIT Bombay but left after a year due to..

Meet student who cleared JEE Advanced with AIR 1, went to IIT Bombay but left after a year due to..![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did Kangana Ranaut party with gangster Abu Salem? Actress reveals who's with her in viral photo

DNA Verified: Did Kangana Ranaut party with gangster Abu Salem? Actress reveals who's with her in viral photo![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: New Delhi Railway Station to be closed for 4 years? Know the truth here

DNA Verified: New Delhi Railway Station to be closed for 4 years? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here

DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() Avneet Kaur shines in navy blue gown with shimmery trail at Cannes 2024, fans say 'she is unstoppable now'

Avneet Kaur shines in navy blue gown with shimmery trail at Cannes 2024, fans say 'she is unstoppable now'![submenu-img]() Assamese actress Aimee Baruah wins hearts as she represents her culture in saree with 200-year-old motif at Cannes

Assamese actress Aimee Baruah wins hearts as she represents her culture in saree with 200-year-old motif at Cannes ![submenu-img]() Aditi Rao Hydari's monochrome gown at Cannes Film Festival divides social media: 'We love her but not the dress'

Aditi Rao Hydari's monochrome gown at Cannes Film Festival divides social media: 'We love her but not the dress'![submenu-img]() AI models play volley ball on beach in bikini

AI models play volley ball on beach in bikini![submenu-img]() AI models set goals for pool parties in sizzling bikinis this summer

AI models set goals for pool parties in sizzling bikinis this summer![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?

DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?![submenu-img]() Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?

Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() Nargis, Bina Rai, Suraiya rejected this role, chosen actress refused Filmfare Award, film became classic, is based on...

Nargis, Bina Rai, Suraiya rejected this role, chosen actress refused Filmfare Award, film became classic, is based on...![submenu-img]() Jitendra Kumar says there is scope for multiple seasons of Panchayat, opens up on chances of season 4 | Exclusive

Jitendra Kumar says there is scope for multiple seasons of Panchayat, opens up on chances of season 4 | Exclusive![submenu-img]() Randeep Hooda marks Swatantrya Veer Savarkar OTT release with visit to cellular jail in Andaman, sees Savarkar's cell

Randeep Hooda marks Swatantrya Veer Savarkar OTT release with visit to cellular jail in Andaman, sees Savarkar's cell![submenu-img]() Jackie Shroff breaks his silence on Delhi HC order protecting personality rights: 'Misuse dilutes our brand equity'

Jackie Shroff breaks his silence on Delhi HC order protecting personality rights: 'Misuse dilutes our brand equity'![submenu-img]() Canadian DJ deadmau5 returns to India after a decade; know when, where to watch him perform live

Canadian DJ deadmau5 returns to India after a decade; know when, where to watch him perform live ![submenu-img]() Meet Mukesh Ambani's bahu Radhika Merchant's makeup artist, whose client is Alia Bhatt, her fees is...

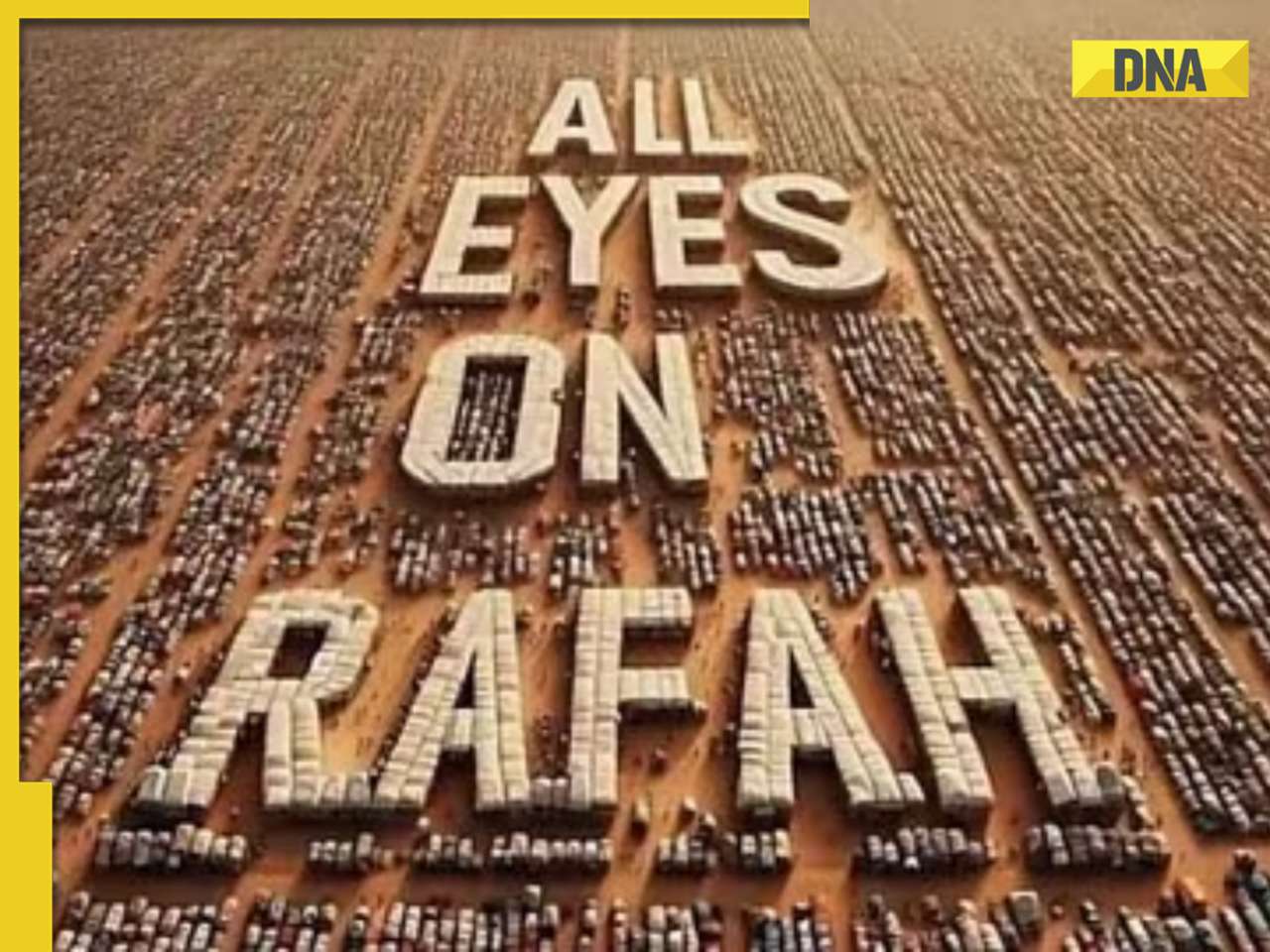

Meet Mukesh Ambani's bahu Radhika Merchant's makeup artist, whose client is Alia Bhatt, her fees is...![submenu-img]() 'All Eyes On Rafah' campaign goes viral on social media, here's what the image means

'All Eyes On Rafah' campaign goes viral on social media, here's what the image means![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's 2nd pre-wedding bash begins today: Know all details here

Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani, Radhika Merchant's 2nd pre-wedding bash begins today: Know all details here![submenu-img]() Viral video: Woman takes over streets of London in lungi, here’s how locals reacted

Viral video: Woman takes over streets of London in lungi, here’s how locals reacted![submenu-img]() Which countries are witnessing rapid increase in Muslim population? Where does India stand? Check full list here

Which countries are witnessing rapid increase in Muslim population? Where does India stand? Check full list here

)

)

)

)

)

)