Charles Ponzi was a legend, but for all the wrong reasons, writes Mitchell Zuckoff.

MUMBAI: “Just after four o’ clock, Ponzi wandered outside to buy the afternoon papers, generously tipping the first newsboy he came across. As he did, someone in the crowd yelled, “You’re the greatest Italian in history!”

“No,” Ponzi answered with a laugh. “I am the third greatest. Christopher Columbus discovered America and Marconi discovered the wireless.” The fan cried out, “You discovered money!”

These lines from Mitchell Zuckoff’s book, Ponzi’s Scheme, The True Story of a Financial Legend, point to the popularity Charles Ponzi, an Italian immigrant into the United States.

On November 3, 1903, Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi boarded the S S Vancouver, bound for Boston. He survived doing odd jobs around in the US and Canada, was jailed a couple of times and changed his name to a more American sounding Charles.

After a series of jobs, Ponzi started “Charles Ponzi, export and import” with the plan of working as a commission agent for companies who were hoping to do some international trading. But there was a slight problem - Ponzi did not have any contacts.

“To attract business, Ponzi thought about printing circulars and sending blanket mailings to potential clients. But that would cost him a nickel per circular for domestic companies and eight cents each for international firms. Ponzi realised he would be wiped out by mailing fees before he collected his first commission. Instead, he decided to advertise in foreign trade magazines, but again he was stymied by the cost,” writes Zuckoff.

“That led to a new plan: He would start his own foreign trade publication, one whose huge circulation would allow him to charge lower advertising rates for budding entrepreneurs like him. Inspired, he had a new sign painted on his door - The Bostonian Advertising and Publishing Company - and set out launching a publication called the Trader’s Guide.”

Ponzi planned to mail 100,000 free copies to company whose names he found in the US Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce and the US Consular Service. The plan was to keep doubling circulation every six months.

As Zuckoff writes, “The initial mailing, he thought, would cost him thirty-five cents a copy, or $35,000. To meet that cost, he would lard a two-hundred page guide with 150 pages of advertising. The ads would cost $500 a page, with a premium of $5,000 for the cover page, for a total imagined advertising income of $80,000. After expenses, he figured out a profit of at least $15,000 in the first six months. He expected his profits would double as many times as he doubled circulation.”

But, things did not work as planned. And then serendipity struck. In August 1919, he got a letter from a gentleman in Spain inquiring about the Trader’s Guide. “To pay the postage, the Spaniard had pinned to the corner of his letter a strange piece of paper,” writes Zuckoff. It was an international reply coupon, which could be exchanged for American stamps. The innocuous financial instrument gave Ponzi an idea.

As Zuckoff writes, “The coupon had cost the Spaniard thirty centavos, or roughly six cents. After a penny towards processing fees, it could be exchanged in the United States for a stamp worth five cents. Using exchange rates published in Boston newspapers, Ponzi concluded that a dollar was worth six and two-thirds pesetas. Because there were one hundred centavos to a peseta, Ponzi calculated that a dollar was worth 666 centavos. If each International Reply Coupon cost thirty centavos, a dollar could buy twenty-two of the coupons in Spain. If Ponzi brought them to the United States, those twenty-two coupons would be worth five cents each, or a total of dollar and ten cents. By redeeming them in Boston rather than Barcelona, Ponzi would earn a profit before expenses of 10 cents or 10 percent, on each dollar’s worth of coupons he bought in Spain and redeemed them in United States.”

He soon figured out that this would work with other currencies. On the Italian lira, with the same logic, he could hope to earn profits of $2.3 on every dollar invested.

But, there was a slight problem. As Zuckoff writes “The hitch, Ponzi understood, would be getting cash for the stamps he bought with the coupons. One possibility would be to sell the stamps at a slight discount to business that used large amounts of postage, giving them a bargain on a necessary item while still maintaining huge profits for Ponzi.” These details Ponzi thought could wait for later. But, as he would soon figure out, this would ultimately lead to his downfall.

What was now needed was money to exploit the opportunity. Ponzi started the Securities Exchange Company, and offered the investors 50% interest on 90-day investments. Though the certificate given to investors promised 50% interest in 90 days, Ponzi told the investors he would to shorten the pay-off period to around 45 days.

As the news spread, more and more people started investing in the scheme. At its peak, it is said that investors had invested around $15 million in the scheme. But Ponzi knew that even though he had a business model in place, he hadn’t figured out a way of earning money. He was essentially following the old scam of robbing Peter to pay Paul i.e. the money being brought in by the newer investors was being used to pay off the investors whose investments were maturing.

Soon the regulatory authorities came visiting. Ponzi, who had been thinking of other ways of legitimising his business, made a bold proposal to them. He decided to open the books of his Securities and Exchange Company to an auditor. The auditor would establish his liabilities. After that, his only job would be to show that he had the assets to back it up. Also during this period, no new deposits would be taken. Investors who wanted to redeem their investment before maturity would be given their principal back without interest.

Ponzi knew that every investor who withdraws before maturity, would mean lesser debt. His calculations told him that he had issued promissory notes of around $15 million. He had around $8 million with him, which meant he was $7 million short, Early withdrawals, he felt, would wipe out around $4 million in liabilities, after which, he would be $3million in debt. This he felt he could manage from a bank he was a director. After this, he would stop taking deposits and get into other genuine businesses for which he would raise money from the public, promising them a reasonable return.

But things did not work out as planned. The Boston Post kept doing stories to prove that Ponzi did not have a magic formula, and was only robbing Peter to pay Paul. On August 13, 1920, Ponzi was arrested. Sometime later he was convicted for 5 years in prison.

And thus ended the story, of the man who wanted to be king, but ended up giving his name, to what is now famously known as the Ponzi scheme. On his death bed Ponzi finally admitted: “My business was simple. It was the old game of robbing Peter to pay Paul. You would give me one hundred dollars and I would give you a note to pay you one hundred-and-fifty dollars in three months. Usually I would redeem my note in forty-five days. My notes became more valuable than American money....Then came trouble. The whole thing was broken”.

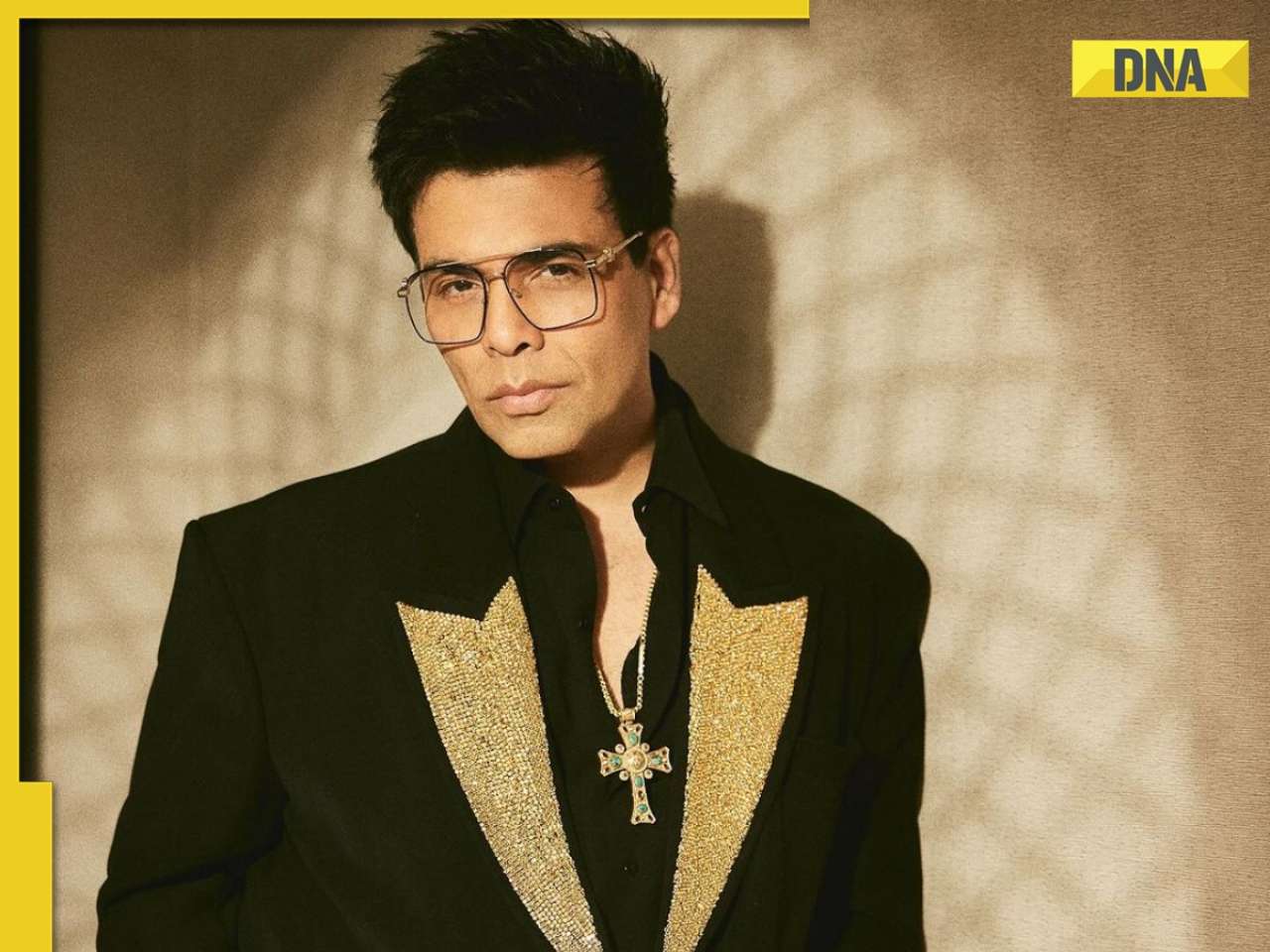

![submenu-img]() Meet India's highest paid director, charges 30 times more than his stars; not Hirani, Rohit Shetty, Atlee, Karan Johar

Meet India's highest paid director, charges 30 times more than his stars; not Hirani, Rohit Shetty, Atlee, Karan Johar![submenu-img]() Indian government issues warning for Google users, sensitive information can be leaked if…

Indian government issues warning for Google users, sensitive information can be leaked if…![submenu-img]() Prajwal Revanna Sex Scandal Case: Several women left home amid fear after clips surfaced, claims report

Prajwal Revanna Sex Scandal Case: Several women left home amid fear after clips surfaced, claims report![submenu-img]() Meet man who studied at IIT, IIM, started his own company, now serving 20-year jail term for…

Meet man who studied at IIT, IIM, started his own company, now serving 20-year jail term for…![submenu-img]() Gautam Adani’s project likely to get Rs 170000000000 push from SBI, making India’s largest…

Gautam Adani’s project likely to get Rs 170000000000 push from SBI, making India’s largest…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates

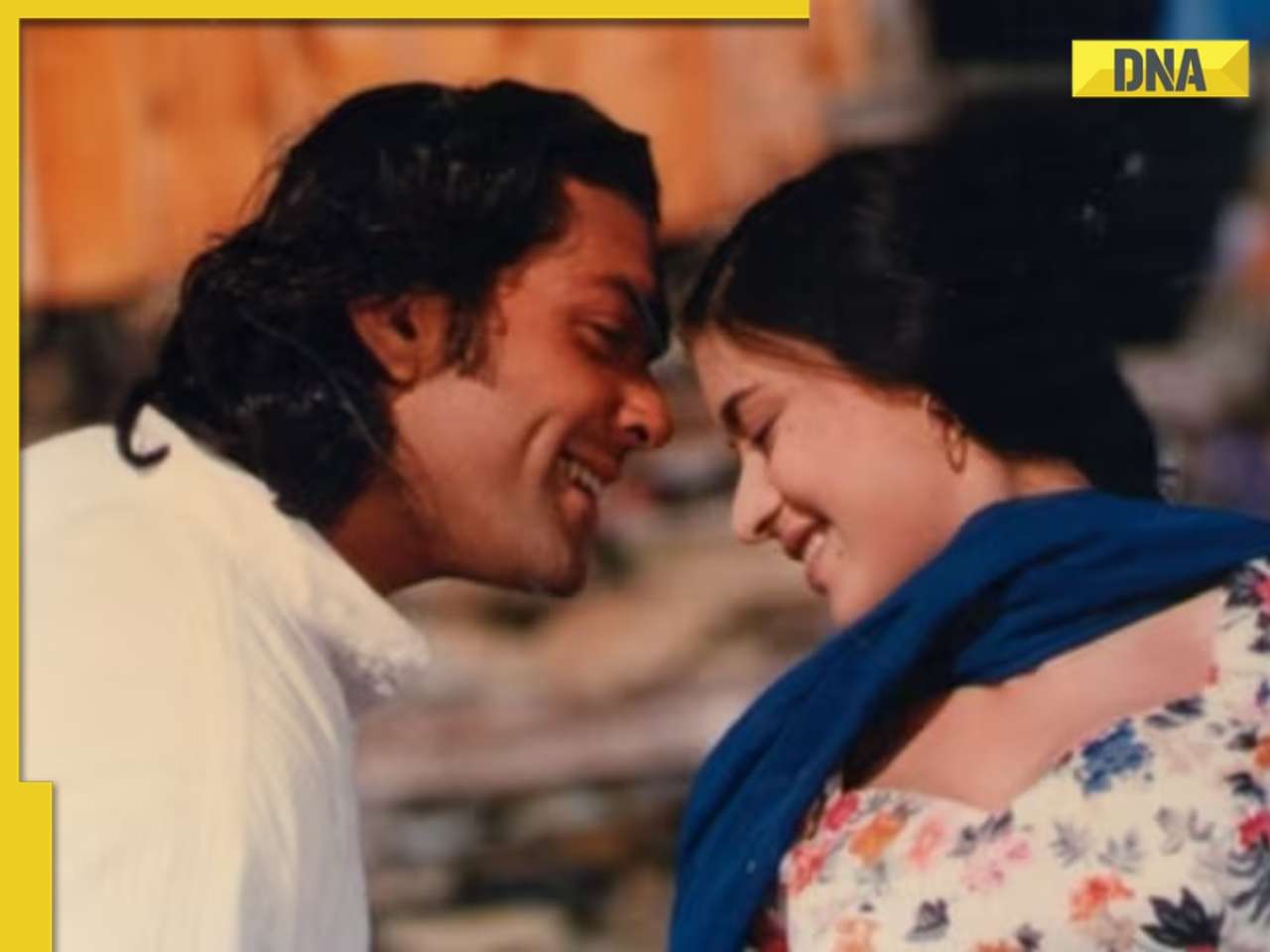

Jr NTR-Lakshmi Pranathi's 13th wedding anniversary: Here's how strangers became soulmates![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Heeramandi, Shaitaan, Manjummel Boys, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Meet India's highest paid director, charges 30 times more than his stars; not Hirani, Rohit Shetty, Atlee, Karan Johar

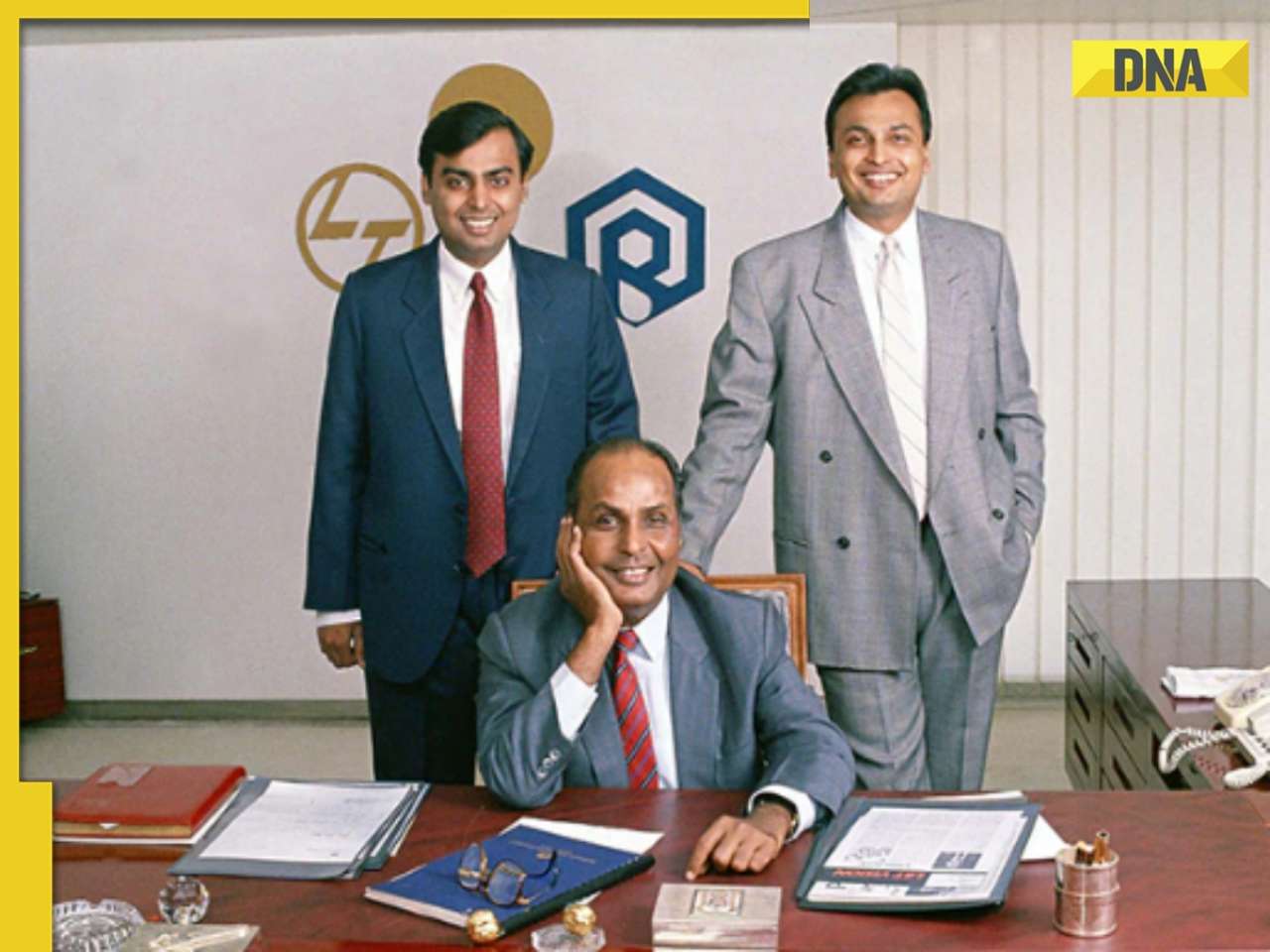

Meet India's highest paid director, charges 30 times more than his stars; not Hirani, Rohit Shetty, Atlee, Karan Johar![submenu-img]() This superstar worked as clerk, was banned from wearing black, received death threats; later became India's most...

This superstar worked as clerk, was banned from wearing black, received death threats; later became India's most...![submenu-img]() Karan Johar slams comic for mocking him, bashes reality show for 'disrespecting' him: 'When your own industry...'

Karan Johar slams comic for mocking him, bashes reality show for 'disrespecting' him: 'When your own industry...'![submenu-img]() Kapoor family's forgotten hero, highest paid actor, gave more hits than Raj Kapoor, Ranbir, never called star because...

Kapoor family's forgotten hero, highest paid actor, gave more hits than Raj Kapoor, Ranbir, never called star because...![submenu-img]() Meet actress who lost stardom after getting pregnant at 15, husband cheated on her, she sold candles for living, now...

Meet actress who lost stardom after getting pregnant at 15, husband cheated on her, she sold candles for living, now...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Kolkata Knight Riders take top spot after 98 runs win over Lucknow Super Giants

IPL 2024: Kolkata Knight Riders take top spot after 98 runs win over Lucknow Super Giants![submenu-img]() ICC Women’s T20 World Cup 2024 schedule announced; India to face Pakistan on....

ICC Women’s T20 World Cup 2024 schedule announced; India to face Pakistan on....![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Bowlers dominate as CSK beat PBKS by 28 runs

IPL 2024: Bowlers dominate as CSK beat PBKS by 28 runs![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Big blow to CSK as star pacer returns home due to...

IPL 2024: Big blow to CSK as star pacer returns home due to...![submenu-img]() SRH vs MI IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

SRH vs MI IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Job applicant offers to pay Rs 40000 to Bengaluru startup founder, here's what happened next

Job applicant offers to pay Rs 40000 to Bengaluru startup founder, here's what happened next![submenu-img]() Viral video: Family fearlessly conducts puja with live black cobra, internet reacts

Viral video: Family fearlessly conducts puja with live black cobra, internet reacts![submenu-img]() Woman demands Rs 50 lakh after receiving chicken instead of paneer

Woman demands Rs 50 lakh after receiving chicken instead of paneer![submenu-img]() Who is Manahel al-Otaibi, Saudi women's rights activist jailed for 11 years over clothing choices?

Who is Manahel al-Otaibi, Saudi women's rights activist jailed for 11 years over clothing choices?![submenu-img]() In candid rapid fire, Rahul Gandhi reveals why white T-shirts are his signature attire, watch

In candid rapid fire, Rahul Gandhi reveals why white T-shirts are his signature attire, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)