Behind the glamour and the glycerine of daily soaps is a parallel universe of gruelling schedules, sleepless nights and punishing deadlines.

Behind the glamour and the glycerine of daily soaps is a parallel universe of gruelling schedules, sleepless nights and punishing deadlines. Taran N Khan discovers the dark side of Mumbai’s glittering television industry.

Aniruddha Sharma, 26 and heavy-eyed, sits slumped on his chair, chain smoking and glaring at a monitor, which, at the moment, is showing a bright yellow wall. “Your work is never done in this field,” says the director, who has helmed three major daily soaps. “I once spent five hours shooting a sequence where the female lead is suffering her in-laws’ taunts silently. It was gruelling and back- breaking, but we finally made it to the last shot.” That was when he got a phone call from his office, asking him to re-shoot the entire scene since “someone had decided that instead of being docile the character would now be aggressive and hard, take on a Durga ka roop. I didn’t even argue. There is no choice—everybody works like this. In television,” he says, lighting another cigarette, “you are always on the edge.”

Nine years after India’s first daily soap went on air, Mumbai’s television industry has morphed into a place where a 12- hour shift counts as an easy day, directors refer to themselves as ‘daily labour’ and a month has 45 working days, counting night shifts. “People consider films to be the most disorganised industry,” says Sunil Bohra, producer. “Multiply that chaos by a thousand and you get television today.” Much of the mayhem, he says, is in the area of daily soaps. “We exist in a parallel universe, with its own time zone and logic,” says Ram Kumar, executive producer. “We exist like these mobile phones,” cuts in his colleague Sandeep Paswan, waving his own slim handset. “We keep working until the battery is drained out.”

“It’s not just that the hours are long,” says Waseem Sabir, director, “but that they fluctuate between any time of day or night.” Unlike other jobs, he adds, you never know when your shift will end. “If you get off at 3am, you get no recovery time,” he adds. “It’s back to work at 7am.” Part of the reason for these killing schedules is tied into the logic of producing a daily, says Kumar. “There are too many variables squeezed into too little time, which makes things go crazy,” he says. The real problem, contends Amit De, editor, is the insecurity over TRPs. “We never get into a show with adequate planning or a bank of episodes,” he says, “because the channel is too busy looking over its shoulder at what clicks on other networks to approve screenplays too far in advance.” The result is an industry where crews shoot during the day for the evening’s broadcast, and scripts are faxed to the location.

“The pressure starts right at the top and trickles down,” says Shraddha Nigam, actress. The established star dropped out of daily soaps since she couldn’t handle the pressure. Rajiv Khandelwal, one of the biggest names on TV, insists on doing “just one show at a time, because I love myself too much.” He recently started carrying a mixer and a bag of fruits to the sets “so I can have fresh juices as I wait.” Sometimes, he says, it would be nice if producers realised that actors are different from props, “but given the rates stars charge, it is justified that they should work hard.” Adds Nigam, “It’s where the big bucks are, but I get too scared of committing all my time to one project. It’s too much like marriage. You have to be excited about it to make it work.”

“Sleep is an issue,” says Ratna Sheshadri, actress, with a note of longing in her voice. It is past midnight and she has been on the set since 7am, sitting under the blazing lights of the eternal daytime of studios. “The waiting is the hardest part,” she says, idly fingering her iPod. “I have been in costume and makeup for the past six hours because I don’t know when I may be needed.” Sheshadri recently took on a minor role in a second soap, a step up professionally. “You must be seen for the public to know you, to do better,” she gushes. But the non-stop churning is taking a toll. Recently, in the whirl of similar looking sets, heavy costumes and fake jewellery, she admits to having blanked out. “I lost track of who I was playing and even where I was,” she admits. Despite this, she is eager to continue. “I am just beginning, and everything seems glamourous and desirable to me right now,” she smiles.

“Behind the glamour and the pretty faces is the pressure we deal with every day,” says Bohra. “You’re hard at work and the next thing you know you are a picture on the wall with a garland around you. That’s the kind of tension we’re talking about.” For Adil Imam, assistant director, the death of his colleague from sheer exhaustion was a reality check. “One of my friends suffered a head on collision while riding his bike from Andheri to Mira Road after a 30 hour shoot,” he says. “We’ll never know for sure, but the chances are that he fell asleep while driving.” In the three years he worked for a production house, Imam would routinely carry an extra shirt and a toothbrush to office. While he was young enough to enjoy the buzz, most of his bosses “were either divorced or on the verge of a breakup,” he says. “The rest of your life recedes into the background,” explains Rahib Siddiqui, director. “It’s just shoot, go home, sleep and then repeat. Nothing matters above delivering that tape on time.”

Trying to break out from this system, says De, is impossible in an insecure and competitive industry. “If a director refuses to shoot 10 scenes a day, there will be many more ready to do 14,” he says.”There is no shortage of human resource in this field. You can see them standing outside production houses everyday, hoping to get in.” “When someone sits at home unemployed for a year, no one asks him how he is coping,” says Siddiqui. “So when there are projects going, you take all you can get, even if it ruins your life and health.”

“You say you do it for passion,” says Kumar, “but you really do it for money.” The regularity of payments and higher rates than films have made it a “get-rich-quick-scheme for many,” says Bohra. “Even though they curse this line they keep at it because where else will they get such money?” he asks.

Adds Siddiqui, “Everybody in this industry is out to build a name and is ready to do whatever it takes. There is a certain grind you go through. Once you are ‘somebody’, you get to do things your way. Right now,” he says, gesturing at the cardboard walls and harsh lights around him, “I am doing the grind.”

Some names have been changed on request

![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here

DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() Hassan horror: Sex scandal Prajwal Revanna breaks silence, to appear before SIT on...

Hassan horror: Sex scandal Prajwal Revanna breaks silence, to appear before SIT on...![submenu-img]() Shakira likely to perform at Anant Ambani-Radhika Merchant’s 2nd pre-wedding bash; she will charge…

Shakira likely to perform at Anant Ambani-Radhika Merchant’s 2nd pre-wedding bash; she will charge…![submenu-img]() Divya Agarwal sparks divorce rumours with Apurva Padgaonkar three months after marriage, deletes...

Divya Agarwal sparks divorce rumours with Apurva Padgaonkar three months after marriage, deletes...![submenu-img]() Noida news: IRS officer arrested for allegedly killing woman whom he met on dating app

Noida news: IRS officer arrested for allegedly killing woman whom he met on dating app![submenu-img]() Meet man who was hired for record-breaking pay package, not from IIT or IIM, his salary is…

Meet man who was hired for record-breaking pay package, not from IIT or IIM, his salary is…![submenu-img]() IIT graduate got job with Rs 100 crore salary, fired within a year, replaced by woman with Rs 33 crore pay, she is...

IIT graduate got job with Rs 100 crore salary, fired within a year, replaced by woman with Rs 33 crore pay, she is...![submenu-img]() Meet youngest IAS officer of her batch, who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...

Meet youngest IAS officer of her batch, who cracked UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Maharashtra SSC Result 2024: MSBSHSE Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here

Maharashtra SSC Result 2024: MSBSHSE Class 10 results to be out today; check time, direct link here![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer, son of grocery store owner, who left Rs 25 lakh job to crack UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR..

Meet IAS officer, son of grocery store owner, who left Rs 25 lakh job to crack UPSC exam in first attempt, secured AIR..![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here

DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() Avneet Kaur shines in navy blue gown with shimmery trail at Cannes 2024, fans say 'she is unstoppable now'

Avneet Kaur shines in navy blue gown with shimmery trail at Cannes 2024, fans say 'she is unstoppable now'![submenu-img]() Assamese actress Aimee Baruah wins hearts as she represents her culture in saree with 200-year-old motif at Cannes

Assamese actress Aimee Baruah wins hearts as she represents her culture in saree with 200-year-old motif at Cannes ![submenu-img]() Aditi Rao Hydari's monochrome gown at Cannes Film Festival divides social media: 'We love her but not the dress'

Aditi Rao Hydari's monochrome gown at Cannes Film Festival divides social media: 'We love her but not the dress'![submenu-img]() AI models play volley ball on beach in bikini

AI models play volley ball on beach in bikini![submenu-img]() AI models set goals for pool parties in sizzling bikinis this summer

AI models set goals for pool parties in sizzling bikinis this summer![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?

DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?![submenu-img]() Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?

Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() Divya Agarwal sparks divorce rumours with Apurva Padgaonkar three months after marriage, deletes...

Divya Agarwal sparks divorce rumours with Apurva Padgaonkar three months after marriage, deletes...![submenu-img]() 'Felt bad for...': Amitabh Bachchan reacts to 'most touching' moment from IPL 2024 KKR vs SRH final

'Felt bad for...': Amitabh Bachchan reacts to 'most touching' moment from IPL 2024 KKR vs SRH final![submenu-img]() Karan V Grover talks about playing Suryapratap in Dhruv Tara, says he enjoys challenging roles | Exclusive

Karan V Grover talks about playing Suryapratap in Dhruv Tara, says he enjoys challenging roles | Exclusive![submenu-img]() Dhadak 2: Karan Johar announces sequel, reveals cast; film to release on...

Dhadak 2: Karan Johar announces sequel, reveals cast; film to release on...![submenu-img]() Munawar Faruqui gets married for second time? Viral inside photo from ceremony has fans puzzled

Munawar Faruqui gets married for second time? Viral inside photo from ceremony has fans puzzled![submenu-img]() Shakira likely to perform at Anant Ambani-Radhika Merchant’s 2nd pre-wedding bash; she will charge…

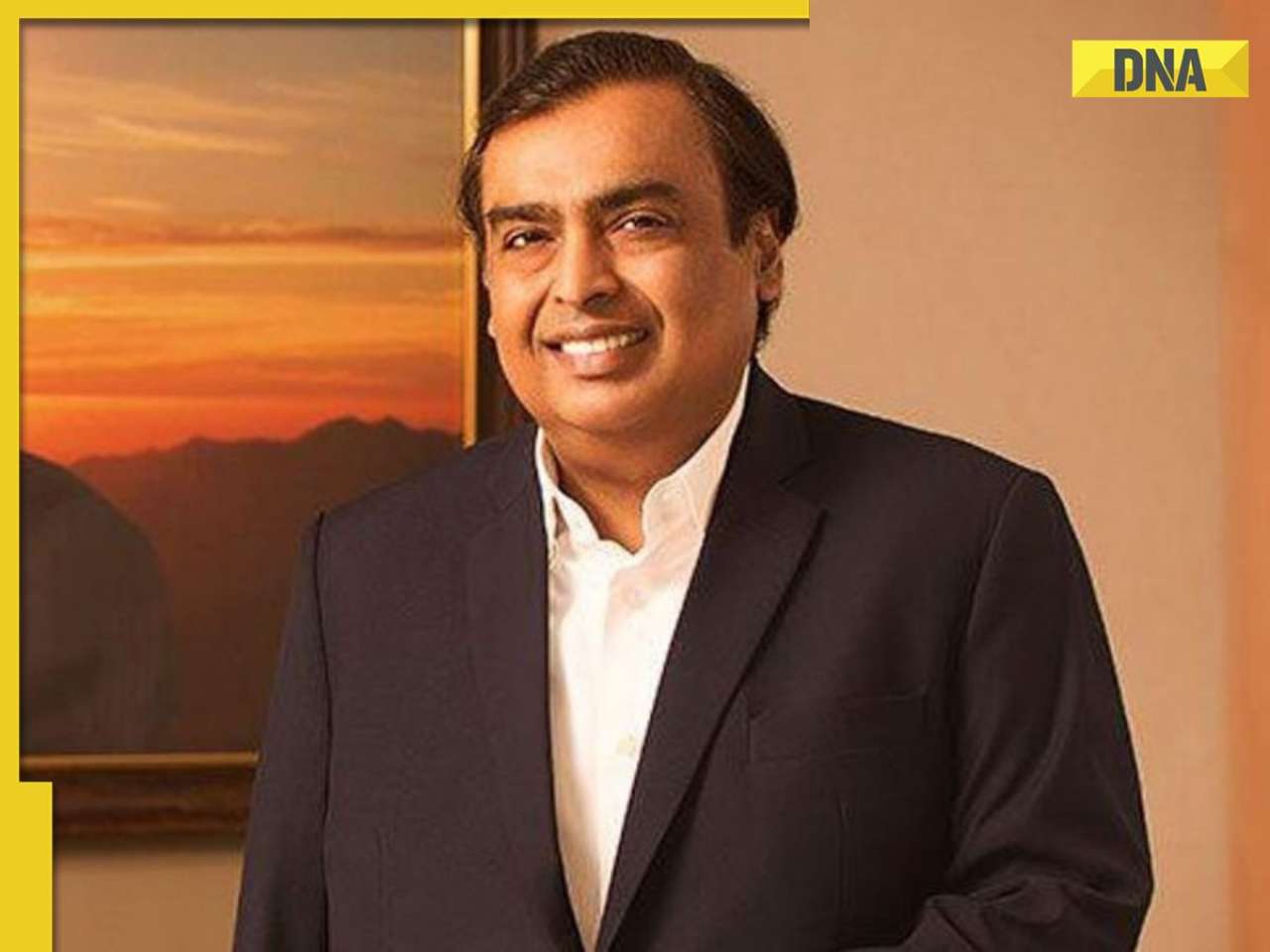

Shakira likely to perform at Anant Ambani-Radhika Merchant’s 2nd pre-wedding bash; she will charge…![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani hosting massive birthday party on cruise for Akash Ambani’s daughter, to be followed by Cannes...

Mukesh Ambani hosting massive birthday party on cruise for Akash Ambani’s daughter, to be followed by Cannes...![submenu-img]() This island has more cats than humans, it is located in...

This island has more cats than humans, it is located in...![submenu-img]() Rapper bets big on Shah Rukh Khan’s KKR, wins over Rs 35000000 after easy IPL 2024 final win

Rapper bets big on Shah Rukh Khan’s KKR, wins over Rs 35000000 after easy IPL 2024 final win![submenu-img]() Hijab, beard is banned in this country with 96% Muslim population

Hijab, beard is banned in this country with 96% Muslim population

)

)

)

)

)

)

)