Most people believe an organ transplant means a fresh lease of life. But few are aware of the struggle that ensues with the body’s immune system.

I’m sorry we don’t allow visitors,” Inderjeet politely but firmly declines any requests to meet her family. That’s because she has been keeping her son, Kamaljeet, 4, in something of a bubble.

When he was about one, doctors discovered the toddler had nephritic syndrome, which damaged his kidneys. He recently had a transplant and is currently on a battery of drugs that ‘suppress’ his immune system to make sure his body does not have an adverse reaction to the new organ. But this has left the youngster so vulnerable, even the slightest infection can be fatal.

The family has stopped going out, except to the doctor’s and the neighbourhood gurdwara; Kamaljeet has been pulled out of his play school to stay home, and his parents’ social life is shot. The toddler spends all his time indoors, and can’t even go out to play. “But he’s very good about it,” says Inderjeet, “Except for his medication-induced mood swings, and crabbiness at being cooped up and having 12-15 medicines a day, he doesn’t complain at all.”

Sadly, the youngster’s life may continue this way for many, many years. He will always live in the shadow of rejection — a medical term for the response of a person’s immune system to any foreign substance, such as the transplanted organ, which it tries to kill, just as it is programmed to do with germs in general.

Kamaljeet may have to take immunosuppressive medication for the rest of his life to keep his new kidney, but this may, in turn, open him up to a host of ailments and infections if he’s not careful.

Vulnerable to infection“Immunosuppressive drugs are the price you pay for accepting an organ,” says nephrologist Umesh Khanna. “In people who are on these drugs, even the slightest illness can become life-threatening. A common cold could turn into pneumonia; a touch of TB of the lungs could spread to the whole body, and an ordinary pani puri-induced gastric irritation could become full-blown septicaemia. Fungal growth, otherwise kept in check naturally by the body, can lead to fungal infections in the brain, lungs and liver.”

Adds Dr Bhupendra Gandhi of Breach Candy Hospital: “A person on immunosuppressives has to be extremely careful for the rest of his life. He can’t eat or drink outside. He has to have well-cooked food at all times. No raw salads or sandwiches.”

Imagine, then, the plight of a person who hopes a transplant — of a heart, kidney, liver, cornea or even skin — will give him a new lease of life, only to discover that the medicines, tests and the post-operative care can make his life almost as restrictive as before.

“You hope that with a new organ, your quality of life will improve and you will be fine for many years,” says Dr Gandhi. “But then, your body doesn’t take to it. I have seen people get extremely depressed about rejection, go back to some form of treatment, but keep hoping they can have another transplant.”

Twice rejectedVikram Philip, 51, is certainly waiting for that. The lawyer has undergone two kidney transplants since 1993, and as many rejections. (The second time, in 2005, he fell so sick because of the immunosuppressive drugs that he had to be taken off them, immediately endangering his newly-acquired kidney.)

“A few years after the transplant, I was travelling again, playing golf everyday and being careful about infections,” he says. “I thought life was back to normal, and that’s where I slipped up. I got pneumonia, septicaemia and a deadly stomach infection, and I’ve spent the last three years in and out of hospitals, never knowing if I’ll make it.”

His family has also changed their ways to accommodate Philip’s delicate state. They eat only leached food, try not to have salads in front of him and “never put spinach and fruits, which I love, on the table”, says Philip. His wife organises her chores around his thrice-weekly visit to the hospital for dialysis. “If I can’t do what I want, I’d rather not have a transplant,” says Philip. “But I’m still hoping to be third time lucky someday.”

Each case is differentRejection, it seems, is inevitable. “It’s the body’s knee-jerk response to something foreign, because that’s how our immune systems are created,” says Dr Bharat V Shah of Lilavati Hospital.

“Otherwise we would be destroyed by germs around us.” And every patient reacts differently to rejection. Some show signs of it while on the operating table (called hyper-acute rejection, usually following an ‘unrelated’ transplant, where the donor and patient’s tissues may be a ‘poor match’); while in others it may show up a few years (acute rejection) or even a decade or more later (chronic rejection). In fact, even the best match cannot guarantee a life without rejection.

When Delhi resident Satish Bakshi opted for a kidney transplant, the organ donated by his sibling was a perfect, 100 per cent match, and should have been totally compatible with his body. But a few years ago, after Bakshi was advised to stop taking the immunosuppressives he was on (a common practice), his body reacted. By the time rejection was detected, it had done irreparable damage.

“Doctors say if they had found out earlier, they could have saved my kidney,” says the 59-year-old businessman. “Now, the only solution is yet another organ transplant.”

A balancing actIndeed, if not detected early, rejection is irreversible. It also forces all doctors dealing with transplants, to tread a fine line. While too little of immunosuppressive drugs causes rejection, too much can lead to toxicity and infection in the body.

“The body is much more tolerant of the liver than the kidney,” says Dr Samir Shah, hepatologist with Jaslok Hospital, adding that of late, he has seen only 10 per cent cases of liver rejection, as opposed to 30 per cent in the case of kidneys. “So we sometimes allow for a mild rejection, rather than pump in more immunosuppressives. But this is a risky step, and we have to keep a close watch.”

The Institute of Transplantation Sciences, Ahmedabad, is working on transplant tolerance. Director HL Trivedi says the idea is to inject stem cells from the donor into the recipient, and when the latter’s immune system gets ready to fight the new cells, to kill the watchdog cells, minimising rejection. “But this is yet to become common practice,” says Dr Shah. “You may have no choice. You can get on dialysis with renal failure. But if you have a bad liver, you have no way out except a transplant.”

![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani’s daughter Isha Ambani’s firm launches new brand, Reliance’s Rs 8200000000000 company to…

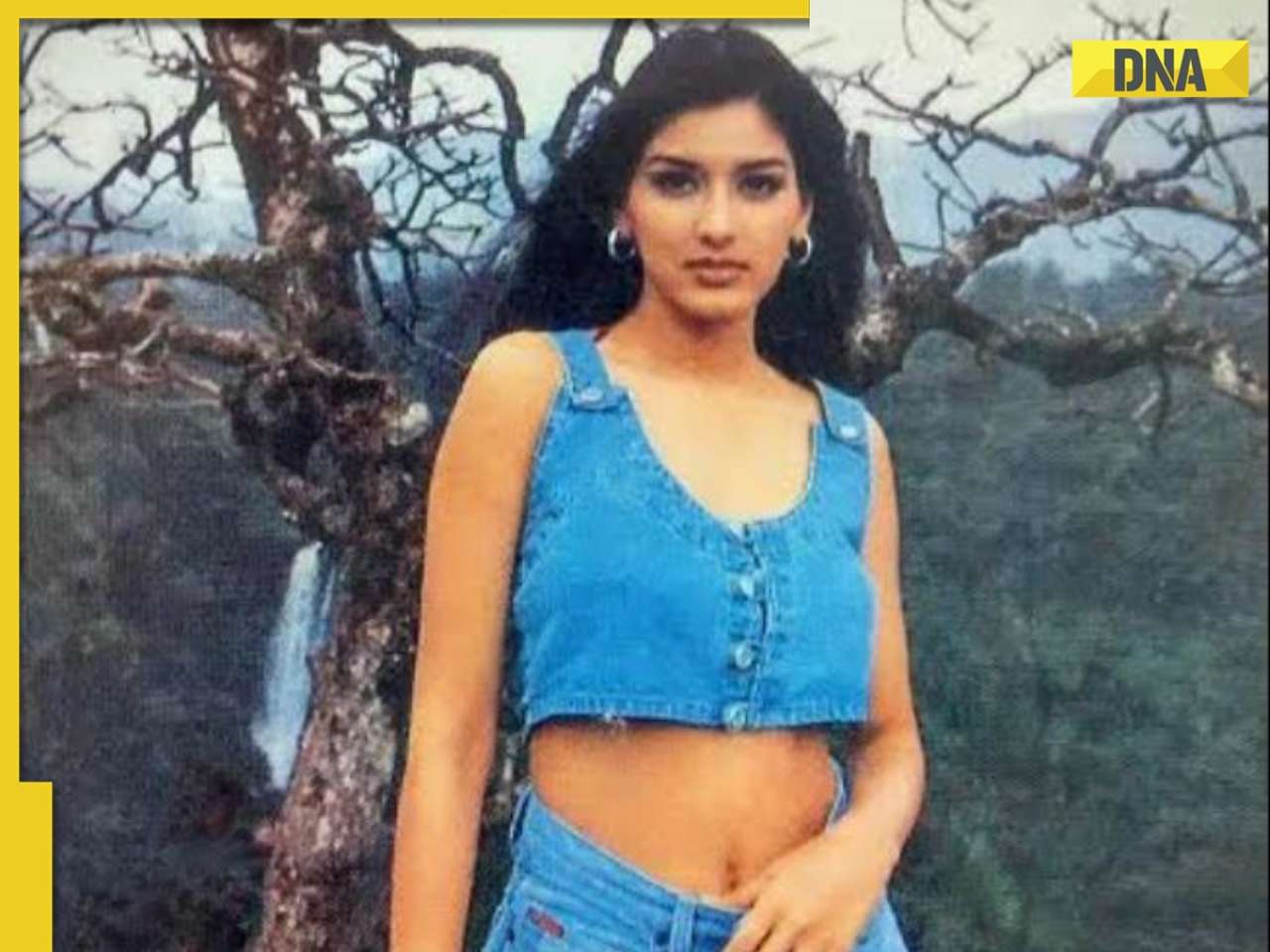

Mukesh Ambani’s daughter Isha Ambani’s firm launches new brand, Reliance’s Rs 8200000000000 company to…![submenu-img]() Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'

Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'![submenu-img]() Heavy rains in UAE again: Dubai flights cancelled, schools and offices shut

Heavy rains in UAE again: Dubai flights cancelled, schools and offices shut![submenu-img]() When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid

When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid![submenu-img]() Gautam Adani’s firm gets Rs 33350000000 from five banks, to use money for…

Gautam Adani’s firm gets Rs 33350000000 from five banks, to use money for…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'

Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'![submenu-img]() When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid

When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid![submenu-img]() Salman Khan house firing case: Family of deceased accused claims police 'murdered' him, says ‘He was not the kind…’

Salman Khan house firing case: Family of deceased accused claims police 'murdered' him, says ‘He was not the kind…’![submenu-img]() Meet actor banned by entire Bollywood, was sent to jail for years, fought cancer, earned Rs 3000 crore on comeback

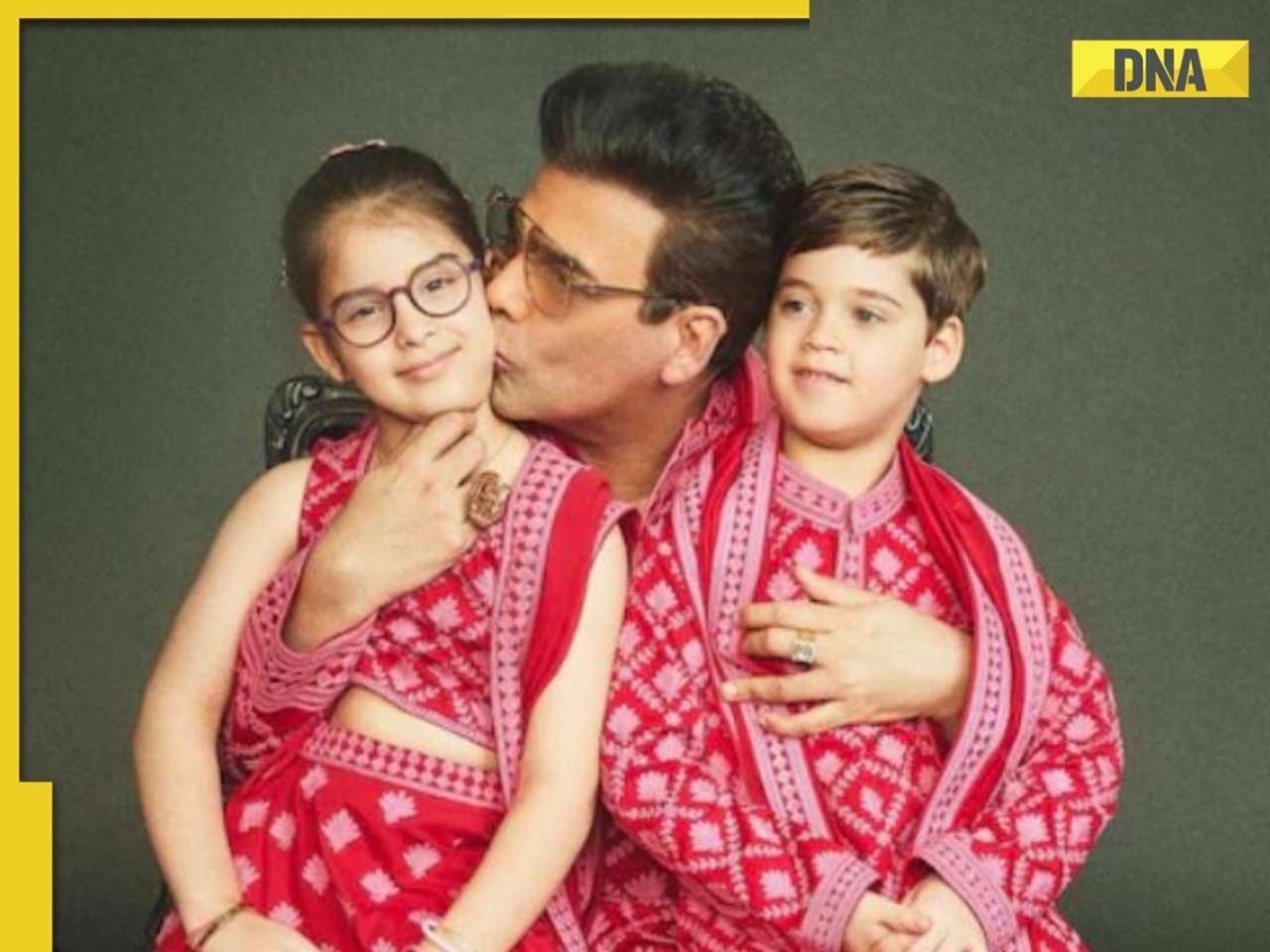

Meet actor banned by entire Bollywood, was sent to jail for years, fought cancer, earned Rs 3000 crore on comeback ![submenu-img]() Karan Johar wants to ‘disinherit’ son Yash after his ‘you don’t deserve anything’ remark: ‘Roohi will…’

Karan Johar wants to ‘disinherit’ son Yash after his ‘you don’t deserve anything’ remark: ‘Roohi will…’![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Bhuvneshwar Kumar's last ball wicket power SRH to 1-run win against RR

IPL 2024: Bhuvneshwar Kumar's last ball wicket power SRH to 1-run win against RR![submenu-img]() BCCI reacts to Rinku Singh’s exclusion from India T20 World Cup 2024 squad, says ‘he has done…’

BCCI reacts to Rinku Singh’s exclusion from India T20 World Cup 2024 squad, says ‘he has done…’![submenu-img]() MI vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

MI vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB and MI still qualify for playoffs?

IPL 2024: How can RCB and MI still qualify for playoffs?![submenu-img]() MI vs KKR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders

MI vs KKR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders ![submenu-img]() '25 virgin girls' are part of Kim Jong un's 'pleasure squad', some for sex, some for dancing, some for...

'25 virgin girls' are part of Kim Jong un's 'pleasure squad', some for sex, some for dancing, some for...![submenu-img]() Man dances with horse carrying groom in viral video, internet loves it

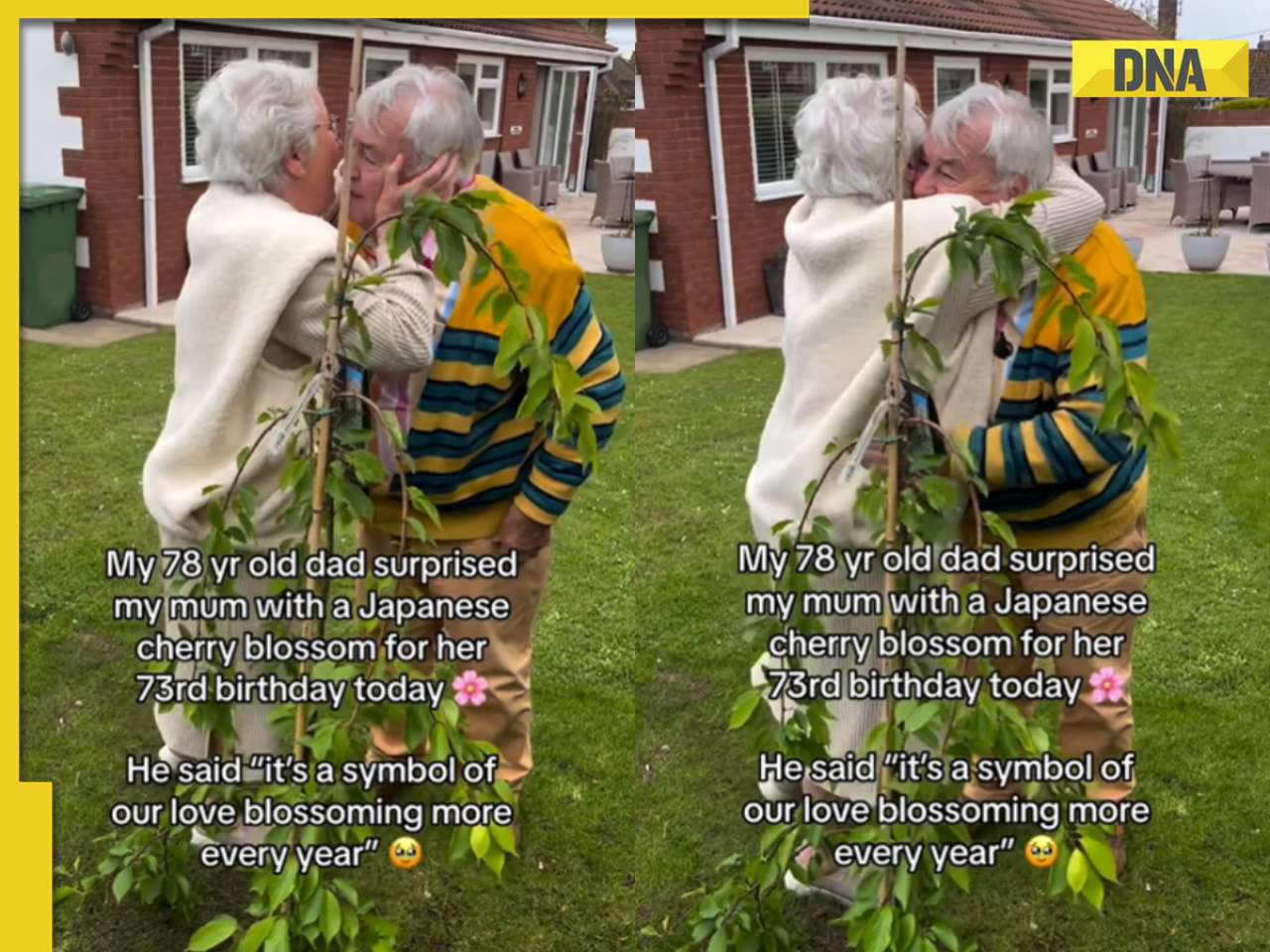

Man dances with horse carrying groom in viral video, internet loves it ![submenu-img]() Viral video: 78-year-old man's heartwarming surprise for wife sparks tears of joy

Viral video: 78-year-old man's heartwarming surprise for wife sparks tears of joy![submenu-img]() Man offers water to thirsty camel in scorching desert, viral video wins hearts

Man offers water to thirsty camel in scorching desert, viral video wins hearts![submenu-img]() Pakistani groom gifts framed picture of former PM Imran Khan to bride, her reaction is now a viral video

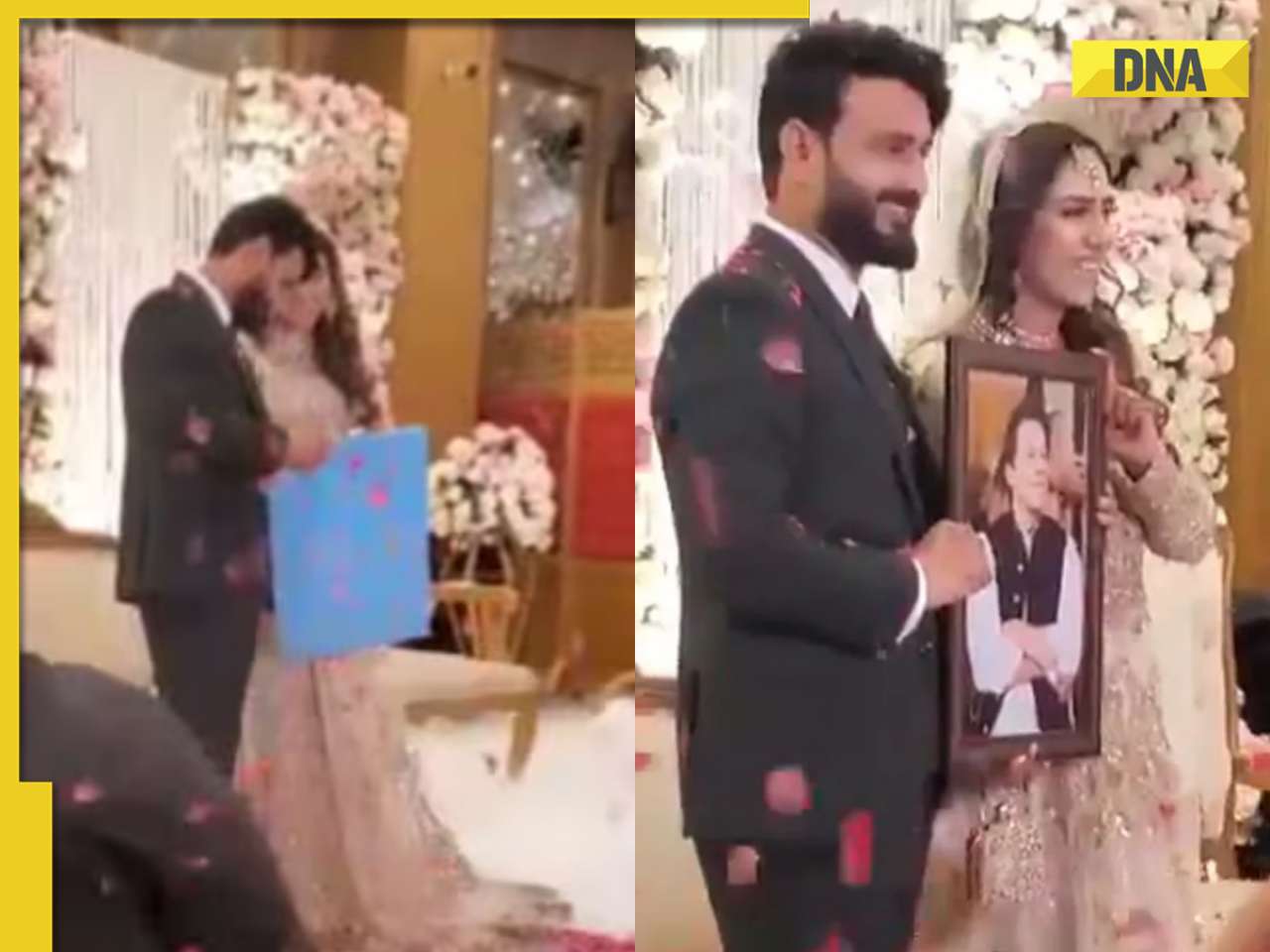

Pakistani groom gifts framed picture of former PM Imran Khan to bride, her reaction is now a viral video

)

)

)

)

)

)