Global markets and economies are like forest fires, trying to micromanage small fires in central banking and fiscal policy can lead to a major disaster.

It was two in the morning, and the boyfriend was fidgeting around, unable to sleep.

“What’s your problem?” I asked. “So jao na!”

“The October heat is just killing this time!” he replied. “And you don’t let me install an AC also.” “Well, AC makes me sneeze badly,” I said.

“Yeah. I know that much about you by now,” he replied.

“So go to sleep!”

“I can’t sleep in this heat. It’s killing me.”

“Go and have a can of Diet Coke, and let me sleep,” I said.

The boyfriend got up, and came back with two cans. “Here you have one,” he said. “Ah. You won’t let me sleep,” I said, and got up.

“You know I was reading in the papers that more efforts are being made to rescue the troubled economies in Europe, especially Greece. Leaders like German chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Nicolas Sarkozy are expected to meet on October 23, 2011, and announce further rescue plans,” he said sipping his can.

“Yes I read that as well.”

“So, the world seems to be moving from one rescue plan to another.”

“Yes it is,” I replied without showing much interest, and sipping on some Coke. “Do you think the rescue efforts will work this time?” he asked. “I wish I knew,” I replied. “But let me talk about something else, nonetheless.”

“Something else?” “Yes, forest fires.” “Now what has that got to do with what we were talking about?”

“Let me explain.”

“Please go ahead.”

“Three researchers, Bruce Malamud, Gleb Morein and Donald Turcotte, at the University of Cornell decided to simulate a forest fire game on the computer."

“First you talked about forest fires, now you are talking about games.”

“Have some patience my dear. So the game is played on a grid.

As Mark Buchanan writes in Ubiquity - The Physics of Complex Systems, “At each time step, the computer plants a tree on a random square. As time runs on, the number of trees grows as they sprout up at random all over the forest. Every so often, after a certain number of trees have been planted, the computer drops a match on a random square. So, we have trees popping up at a uniform rate, one each step, and matches falling on squares at a smaller rate-say, one match for every 200 or 400 trees that sprout. When a match falls, it does nothing if it lands on an open square (that does not have a tree). If it hits a tree, that tree catches fire. The final rule in the game is that, once a tree catches fire, it will at the next step light to any trees that happen to occupy one of the four squares next to it.”

“Interesting.”

“So these researchers tried out various ways and came up with some interesting results. In some cases they dropped a match after 100 trees were planted, and in other cases they dropped a match only after let’s say 2000 trees were planted.”

“And then what happened?” he asked.

“Well, in cases were matches were dropped more frequently, obviously there were many fires. In second cases there was lesser number of fires.”

“Oh, but isn’t that obvious.”

“Yes it is. But here is the interesting part. ‘When 2000 trees were planted for every match dropped...the game typically filled up the entire grid with trees before sparking a single fire. When it finally did, the result was as catastrophic as it was inevitable - a single tree torched a fire that spread across the entire forest. In other words, when the fire starting frequency was very low, the game showed a marked tendency to be catastrophic, all-consuming disasters,’ writes Buchanan.”

“So?” he asked.

“The researchers called this observation the ‘Yellowstone effect’ on the Yellowstone National Park, the first national park in the world, which gets regular forest fires, and some of them have been very big fires.”

“Where are we headed, dear?”

“Have some patience. From 1890, the US Forest Service has had a zero file tolerance policy and so have tried to put out every fire, even those starting due to natural causes. As Buchanan points out ‘This is the real-world equivalent of dropping matches far less frequently in the forest-fire game, and it appears to have similar consequences’.”

“Which means what?”

“When you keep putting out all the fires, it leads to a situation where forests age. ‘Old trees were not replaced by younger trees and the natural evolution of the forest’s materials changed. Dead wood, grass and twigs, brush, bark and leaves accumulated, and as a result, the forests moved away from the natural critical state.

The trouble is that fires are an indispensable component of the natural dynamics that keep forests in that state. So by suppressing them, the forests have instead been driven into an even more unstable state...with a high density of burnable material everywhere...a single lightening strike or cigarette butt can explode into mass fire,’ writes Buchanan.”

“Okay. I get this. But what is the point?” he asked, while sipping on Coke and burping at the same time.

“Now, let me give you another analogy explained in Endgame—The End of the Debt Supercycle and How it Changes Everything, written by John Mauldin and Jonathan Tepper. The authors point out to the example of the states of California in the US and Baja California in Mexico,” I explained.

“What do these guys say?”

“They point out that ‘Global markets and economies are like forest fires. California and Baja California both have very similar forests and vegetation but have different fire control policies. In California, small fires are put out regularly by firefighters. In Baja California, they are not. Paradoxically, this means that Baja California has many more small fires and almost no major fires, while California has very limited small fires and occasional major, catastrophic fires...Without small fires to clear the brush, enrich the soil, and unlock pine seeds, nature aren’t in balance. Avoiding small problems create greater systemic problems when brush between the trees build up.’”

“So?”

“The policy till now, when it comes to all the problems or small fires that the financial crisis is throwing up, is to douse them in various ways. This of course does not solve the problem but just postpones it, and on a later day it manifests into a bigger problem. As Mauldin and Tepper write, ‘Trying to micromanage small fires in central banking and fiscal policy leads to growing confidence by risk takers, so you get fewer small fires and paradoxically a greater chance of a major catastrophic fire’.”

“That’s a different point of view, for sure.”

“As economist Bill Bonner wrote in a recent column, ‘Give disaster a chance to show its stuff. Let calamity have a go at the problem. Let’s all put our hands together and welcome catastrophe. It’s coming, whether we like it or not. So why not like it? Look, who really cares if a few big banks go broke? Who cares if Greece, Portugal and Spain - if it comes to that - are forced out of the EU? Who cares if the bankers don’t get their bonuses…or the speculators don’t get their pay-offs…or pompous officials don’t get to claim they ‘saved the world economy’?’” I explained, sipping the last drop of Coke.

![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?![submenu-img]() 1 dead, many injured after London-Singapore flight hit by severe...

1 dead, many injured after London-Singapore flight hit by severe...![submenu-img]() This film was based on iconic love story, actors and director died midway, was released incomplete 23 years later

This film was based on iconic love story, actors and director died midway, was released incomplete 23 years later![submenu-img]() Meet man who used to go medicine factory in childhood, now runs Rs 109000 crore pharma company, his net worth is...

Meet man who used to go medicine factory in childhood, now runs Rs 109000 crore pharma company, his net worth is...![submenu-img]() Akshay Kumar 'accidently' collided with RTO officer's bike in Bangkok, shares what happened next: 'I immediately...'

Akshay Kumar 'accidently' collided with RTO officer's bike in Bangkok, shares what happened next: 'I immediately...' ![submenu-img]() Maharashtra HSC 12th 2024: Result declared, know how to check

Maharashtra HSC 12th 2024: Result declared, know how to check![submenu-img]() Meet man who topped IIT-JEE, studied at IIT Bombay, then went to MIT, now is...

Meet man who topped IIT-JEE, studied at IIT Bombay, then went to MIT, now is...![submenu-img]() Meet man who once used to sell newspapers at 9, cracked UPSC exam, he is now…

Meet man who once used to sell newspapers at 9, cracked UPSC exam, he is now…![submenu-img]() Meet woman who secured high-paying job, not from IIT, IIM, VIT, her record-breaking package is...

Meet woman who secured high-paying job, not from IIT, IIM, VIT, her record-breaking package is...![submenu-img]() Maharashtra HSC Result 2024: Class 12th result to be released today, know time, steps to check

Maharashtra HSC Result 2024: Class 12th result to be released today, know time, steps to check![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() AI models show bikini style for perfect beach holiday this summer

AI models show bikini style for perfect beach holiday this summer![submenu-img]() Laapataa Ladies actress Chhaya Kadam ditches designer clothes, wears late mother's saree, nose ring on Cannes red carpet

Laapataa Ladies actress Chhaya Kadam ditches designer clothes, wears late mother's saree, nose ring on Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024

Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'

Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'![submenu-img]() Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024

Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?

DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?![submenu-img]() Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?

Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() This film was based on iconic love story, actors and director died midway, was released incomplete 23 years later

This film was based on iconic love story, actors and director died midway, was released incomplete 23 years later![submenu-img]() Akshay Kumar 'accidently' collided with RTO officer's bike in Bangkok, shares what happened next: 'I immediately...'

Akshay Kumar 'accidently' collided with RTO officer's bike in Bangkok, shares what happened next: 'I immediately...' ![submenu-img]() Meet man, his grandfather founded political party, uncle was CM, he ditched it for Bollywood, worked for Bhansali, now..

Meet man, his grandfather founded political party, uncle was CM, he ditched it for Bollywood, worked for Bhansali, now..![submenu-img]() Meet actor who worked with SRK, Salman, Sushmita, gave many flop films, quit acting, married granddaughter of CM..

Meet actor who worked with SRK, Salman, Sushmita, gave many flop films, quit acting, married granddaughter of CM..![submenu-img]() 'Pregnant for sure': Katrina Kaif, Vicky Kaushal's viral video from London sparks pregnancy speculations

'Pregnant for sure': Katrina Kaif, Vicky Kaushal's viral video from London sparks pregnancy speculations ![submenu-img]() Viral video: Bride makes dramatic entrance from giant ice cube at snowy Alpine wedding in Switzerland

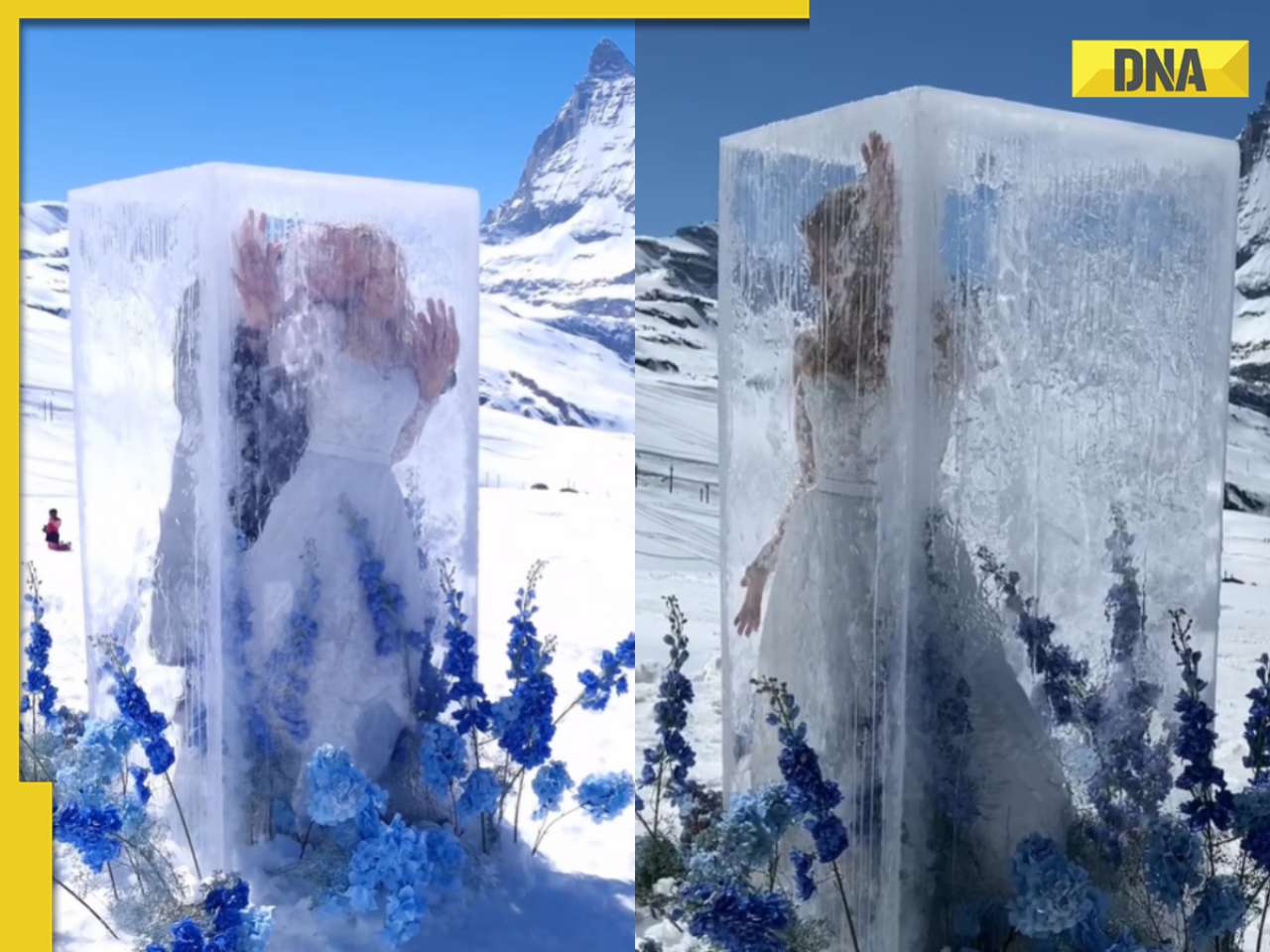

Viral video: Bride makes dramatic entrance from giant ice cube at snowy Alpine wedding in Switzerland![submenu-img]() Elephant lifts safari truck with tourists in shocking viral video, watch

Elephant lifts safari truck with tourists in shocking viral video, watch![submenu-img]() In another gaffe, Joe Biden says he was US 'Vice President' during COVID-19 pandemic, watch viral video

In another gaffe, Joe Biden says he was US 'Vice President' during COVID-19 pandemic, watch viral video![submenu-img]() Meet Nihar Thackeray, lesser-known nephew of Uddhav Thackeray, he is Eknath Shinde's...

Meet Nihar Thackeray, lesser-known nephew of Uddhav Thackeray, he is Eknath Shinde's...![submenu-img]() Heroic buffalo herd rescues one of their own from lion ambush, video is viral

Heroic buffalo herd rescues one of their own from lion ambush, video is viral

)

)

)

)

)

)