Will a new bat make cricket even more of a slam-bam affair or will it be a passing fancy? DNA finds out what the excitement is all about as Mathew Hayden unleashes his secret mongoose

It has already elicited a dozen odd monikers, the least funny of which are ‘a toothpick’, ‘a mace’, and ‘a half-brick on a stick’. They all allude to the new weapon in a batsman’s armoury, the MMi3, which is the smaller, deadlier version of the mongoose bat.

When Matthew Hayden strode out to bat on Friday, apart from the usual excitement over seeing this hard-hitting batsman, viewers were more curious about his bat. Would this be the day when he unleashes his MMi3? In the previous two matches, the little while that Hayden batted, he only used the regular mongoose and not the MMi3. He had said that he would only use the MMi3 at a strategic point, after he had already got his eye in with equipment he’s more familiar with. Well, on Friday, on the hard, new Ferozeshah Kotla wicket, the mongoose with the long handle and short, bottom-heavy blade came out after the first four overs, and it was immediately apparent that this was going to be a game-changer.

Wielding the long handle

But first, the specs of the MMi3. Its blade is one-third shorter than that of a regular bat, while its handle is nearly one-and-a-half times the normal length. So, when it’s time to wield the long handle, which is pretty much all the time in a T20 game once a batsman has got his eye in, the bat’s bottom-weight, faster swing and golf-club kind of torque are designed to send the ball out of the park with minimal effort — provided of course it connects with the ball. (Remember the top third of the blade is missing.)

It probably needed an intelligent cricketer to show us how to use this bat to maximum effect and they don’t come any smarter than Hayden. It isn’t as if he couldn’t have hit the match-winning 93 off 43 balls with a regular bat, which also looks like a toothpick in his hands. But the speed with which even short-arm pulls and wristy flicks flew into the stands made it clear that the mongoose had expanded the range of balls that Hayden could choose to hit for fours and sixes. He only had to remember to use the bottom half of the bat when he pushed for singles, since this bat is not designed for defence. It made things a little simpler for him that Delhi mostly dished out yorkers, medium-pace and spin, without really testing him with short pitch stuff at his body, which the mongoose can’t block.

We’ll see how the mongoose goes against that when Chennai takes on Bangalore next. The mongoose may also be tricky on a sticky wicket where a batsman will have to alternate between attack and defence, treating the ball on merit — but then you hardly expect that kind of a wicket for a T20 game, and in any case Hayden can always opt for the regular-sized bat in such circumstances. As Hayden explains, the bat is innovative, but “the advantage for a batsman should come through the mind rather than other things”.

Bangladeshi cricketer Mohammad Ashraful, who has also been trying out the short-bladed mongoose in domestic matches, provides more insight into its hitting power. “Almost the entire blade of the bat is the sweet spot. So all you need to do is to connect, and the ball literally flies.” It’s also bottom-heavy, with the toe being two inches or more in thickness, which could mean more batsmen will send yorkers for sixes and fours the way Dhoni does.

The changing cricket bat

The mongoose is not the first innovation with a cricket bat, although it may turn out to be the most radical one. David Warner has used a double-sided bat (helpful in reverse-sweeping or switch-hitting) and Ricky Ponting kicked up a row by using a graphite-plated bat packing more punch, which was outlawed by the ICC. But if you thought using graphite-backed bats was unfair, think of how English captain Mike Brearley must have felt when Dennis Lillee walked out into the middle holding an aluminium bat at the WACA in Perth in 1979.

The cricket bat as we know it today only came into existence in the 1770s, when rectangular bats were used for the first time as bowlers were now being allowed to loop the ball up in the air, despite having to bowl it underarm. Before that bats were more like hockey sticks, used horizontally. The bats themselves were made from the heartwood of the English Willow and thus were heavy, as the timber is very dense. It was only in the 1890s that the sapwood of the English Willow came into favour as they made for lighter bats. Batting techniques also reflected these slim, light bats with very thin edges and relatively straight profiles, as batsmen relied more on touch instead of power, and cricketing shots like leg glances and glides gained currency.

Then again, gradually over the years, batsmen started using heavier bats, like the Australian Bill Ponsford in the late 1920s, whose famed “Big Bertha” weighed an ungodly 2 pounds 9 ounces. Later, in the 1960s, players like Graeme Pollock and Clive Lloyd were also adept with heavy bats.

Bat-making technology also improved, with the makers being able to pack in a lot of timber in bats to increase their ‘sweet spots’ and power, and yet keeping the weight manageable.

When batting wasn’t as easy Anshuman Gaekwad, who played Test cricket in the 1970s and 1980s and later became a national coach, eyes the modern bats with envy. “All I remember of my father’s bat (DK Gaekwad played for India in 11 test matches in the 1950s) is how light it used to be. But when I see the kind of bats my son Shatrunjay Gaekwad (First Class cricketer) uses, the comparison is almost shocking. When the ball hit the bat in my playing days, we would feel vibrations. These days, the connection is effortless. My bat used to get a curve only after playing for a season. The curve now comes straight from the manufacturers. Even defensive nudges now go for fours.”

As for the mongoose, Gaekwad is not fully convinced. “I don’t know if batsmen can get accustomed to the changed size and bat speed,” he said.

For Ajit Wadekar, the coming of the mongoose bat only highlights the rapid change that the game is currently undergoing with the advent of T20. “It’s all about entertainment. So a bat like this, only meant for hitting, will find its place.”

Gaekwad was more direct. He felt such equipment for power-hitting will allow less talented batsmen to look as good as the masters. But Marcus Codrington Fernandez, director, Mongoose Cricket and inventor of the bat, was quick to counter that: “With this bat, talented batsman with less brute force will be able to hit sixes more often, not just the physically strong batsmen.”

Doubts will persist, however, until the bat’s uses are proven, or until batsmen learn to exploit it effectively. Ashraful himself doesn’t see anyone opening their innings with the mongoose against fast bowlers. “Imagine facing Steve Harmison or Ishant Sharma with this bat when you are looking to settle in.”

Gaekwad also points to the difficulty in connecting with the ball consistently. “With greater bat speed, players might be inclined to be early into the shot.”

Yusuf Pathan, somebody who you might have thought would grab the Mongoose so that he never again gets caught out on the boundary, is also a sceptic. “Kitna bhi accha bat lekar aao, it will be of no consequence if the bat doesn’t hit the ball. So it’s better to concentrate on the basics,” he told the media. But that was before Hayden’s knock.

Fernandez is not worried about people who think the bat he created may be gimmicky. “Just imagine a set batsman in a T20 situation where he is only looking for big runs. Just imagine the batsman to be Hayden. And then give him the mongoose,” he smiles.

![submenu-img]() Bigg Boss OTT 3: Anil Kapoor confirmed as new host, says 'jhakaas nahi kuch khaas karte hai', leaves netizens divided

Bigg Boss OTT 3: Anil Kapoor confirmed as new host, says 'jhakaas nahi kuch khaas karte hai', leaves netizens divided![submenu-img]() Felony charges and political ambitions: Donald Trump at the legal and electoral crossroads

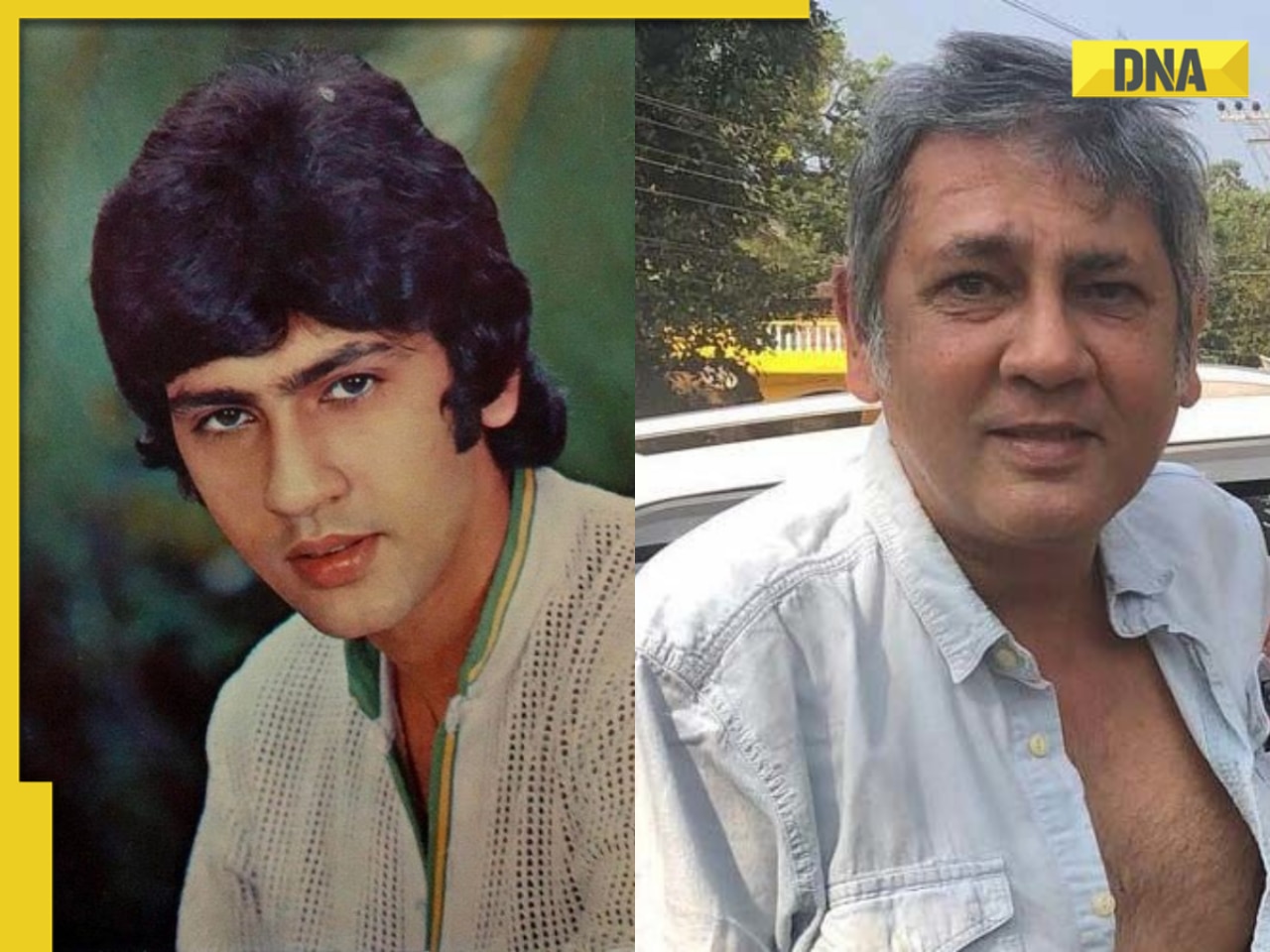

Felony charges and political ambitions: Donald Trump at the legal and electoral crossroads![submenu-img]() This actor left UPSC dreams for Bollywood, was launched by Amitabh, fought Shah Rukh, then disappeared for years, now...

This actor left UPSC dreams for Bollywood, was launched by Amitabh, fought Shah Rukh, then disappeared for years, now...![submenu-img]() Data-Driven Decision Making: Leveraging KPI Metrics for Strategic Insight

Data-Driven Decision Making: Leveraging KPI Metrics for Strategic Insight![submenu-img]() Exploring transformative potential of application modernisation for sustainable solutions in future

Exploring transformative potential of application modernisation for sustainable solutions in future![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who won National Spelling Bee contest in US at age 12, he is from…

Meet Indian genius who won National Spelling Bee contest in US at age 12, he is from…![submenu-img]() Meet man who became IIT Bombay professor at just 22, got sacked from IIT after some years because..

Meet man who became IIT Bombay professor at just 22, got sacked from IIT after some years because..![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius, son of constable, worked with IIT, NASA, then went missing, was found after years in...

Meet Indian genius, son of constable, worked with IIT, NASA, then went missing, was found after years in...![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer who was victim of domestic violence, mother of two, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt, she's posted in

Meet IAS officer who was victim of domestic violence, mother of two, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt, she's posted in![submenu-img]() RBSE Class 5th, 8th Result 2024 Date, Time: Rajasthan board to announce results today, get direct link here

RBSE Class 5th, 8th Result 2024 Date, Time: Rajasthan board to announce results today, get direct link here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did Kangana Ranaut party with gangster Abu Salem? Actress reveals who's with her in viral photo

DNA Verified: Did Kangana Ranaut party with gangster Abu Salem? Actress reveals who's with her in viral photo![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: New Delhi Railway Station to be closed for 4 years? Know the truth here

DNA Verified: New Delhi Railway Station to be closed for 4 years? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here

DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Panchayat season 3, Swatantrya Veer Savarkar, Illegal season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Panchayat season 3, Swatantrya Veer Savarkar, Illegal season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Avneet Kaur shines in navy blue gown with shimmery trail at Cannes 2024, fans say 'she is unstoppable now'

Avneet Kaur shines in navy blue gown with shimmery trail at Cannes 2024, fans say 'she is unstoppable now'![submenu-img]() Assamese actress Aimee Baruah wins hearts as she represents her culture in saree with 200-year-old motif at Cannes

Assamese actress Aimee Baruah wins hearts as she represents her culture in saree with 200-year-old motif at Cannes ![submenu-img]() Aditi Rao Hydari's monochrome gown at Cannes Film Festival divides social media: 'We love her but not the dress'

Aditi Rao Hydari's monochrome gown at Cannes Film Festival divides social media: 'We love her but not the dress'![submenu-img]() AI models play volley ball on beach in bikini

AI models play volley ball on beach in bikini![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, killed in helicopter crash, regarded as ‘Butcher of Tehran’?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?

DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?![submenu-img]() Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?

Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() Bigg Boss OTT 3: Anil Kapoor confirmed as new host, says 'jhakaas nahi kuch khaas karte hai', leaves netizens divided

Bigg Boss OTT 3: Anil Kapoor confirmed as new host, says 'jhakaas nahi kuch khaas karte hai', leaves netizens divided![submenu-img]() This actor left UPSC dreams for Bollywood, was launched by Amitabh, fought Shah Rukh, then disappeared for years, now...

This actor left UPSC dreams for Bollywood, was launched by Amitabh, fought Shah Rukh, then disappeared for years, now...![submenu-img]() Bujii and Bhairava review: Prabhas' futuristic Baahubali-type Kalki 2898 prelude AD is fun, AI Keerthy steals the show

Bujii and Bhairava review: Prabhas' futuristic Baahubali-type Kalki 2898 prelude AD is fun, AI Keerthy steals the show![submenu-img]() This actress gave no hits in 9 years, no Bollywood releases in 5 years, charges Rs 40 crore per film, net worth is..

This actress gave no hits in 9 years, no Bollywood releases in 5 years, charges Rs 40 crore per film, net worth is..![submenu-img]() Mr & Mrs Mahi review: Janhvi, Rajkummar's earnest performances can't save film that doesn't really get cricket or women

Mr & Mrs Mahi review: Janhvi, Rajkummar's earnest performances can't save film that doesn't really get cricket or women![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl’s adorable dance to 'Ruki Sukhi Roti' will melt your heart, watch

Viral video: Little girl’s adorable dance to 'Ruki Sukhi Roti' will melt your heart, watch![submenu-img]() Groom jumps off stage for impromptu dance with friends, viral video leaves netizens in splits

Groom jumps off stage for impromptu dance with friends, viral video leaves netizens in splits![submenu-img]() Viral video: Chinese man stuns internet by balancing sewing machine on glass bottles, watch

Viral video: Chinese man stuns internet by balancing sewing machine on glass bottles, watch![submenu-img]() Watch: First video of Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani-Radhika Merchant's 2nd pre-wedding bash goes viral

Watch: First video of Mukesh Ambani's son Anant Ambani-Radhika Merchant's 2nd pre-wedding bash goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Outrage over woman's dance at Mumbai airport sparks calls for action, watch

Viral video: Outrage over woman's dance at Mumbai airport sparks calls for action, watch

)

)

)

)

)

)