Reeta Prajapati says that her struggle to adopt a child can make enduring labour pains look easy.

I hated children’s birthday parties.

The cakes, the celebrations, the gifts, children giggling and running all around - everything reminded me of only one thing, that I was 40 and I had no baby. Worse, I may never have one.

I was losing time. No baby was on the way. What if no baby would come? What was the matter with me? Women around me easily got pregnant. My younger sister did five years ago. I stayed with her during her pregnancy, held her hand when she delivered a handsome baby boy. And I saw her world change overnight. My parents pampered my nephew, relatives swarmed around, as did I, to spoil the new member. I could see my sister felt like a whole new person. She was a mother and the world saw her differently. I, too, longed for that transition.

After I turned 30 in 2000, I switched 10 gynaecologists over the next 8 years. I lost count of the number and the types of treatments I underwent. Most promised definite results, but I got none.

In November 2008, I decided to give IVF a shot. I was aware of the severe side effects and its low success rate, but I had made up my mind. Doctors told me I needed a lot of rest throughout the treatment. I quit my job of 15 years — a job that had shaped my identity — pooled in all our savings and fixed an appointment.

The dream of having a child takes a toll on you alright. IVF is an expensive procedure, takes up all your time, and most of all, it’s emotionally wrenching. It gives you some hope, but the inevitable desperation and fear drains you, too. It starts with a surgery, followed by daily doses of injections for 15 days, regular visits to the hospital and heavy drugs with side effects that may last you a life time. My back still hurts a year after the treatment.

Then comes the wait for the results. On March 15, 2009, my report was out — it was negative. It made me dizzy. I couldn’t resume my job. For six months, I sat around, as if I was waiting for something to come along miraculously and fix everything. I would sit by the window for hours, numb, and cry myself to sleep every night. My husband had made peace with our childlessness. He said he could live with it. But I couldn’t.

After a few months, I decided I was ready to adopt. I called up a counsellor, completed the formalities and waited yet again. But this was different, I was more patient. I read up everything about adoption and called up the organisation every few weeks. They always said the same thing: “There is a long waiting list. No baby is available yet.” I found that difficult to believe. How could there be no baby “available”? Unfortunately, children are abandoned everyday. Week after week, I read stories about new-born babies thrown in gutters or left naked in garbage bins. My head throbbed at the reality. I once read about a baby who died in a dustbin on the day of the elections because the police were too busy guarding polling booths. The place was only a few kilometres from my home. I couldn’t take it.

I remember sitting alone by the window on the last day of Ganapati Visarjan. It was pouring heavily when I got the call. There was a baby girl in a remote village five hours from Bhubaneshwar.

“She is a few months old. Do you want her?” asked the counsellor.

I called up my husband and we booked tickets to Bhubaneshwar.

Two days later, along with a representative from the adoption agency, we were off to a village called Kendrapada in Orissa. It was a remote place and the roads were rocky. Electricity was a luxury. When we reached there, a woman from the ashram met us with a coarse, soiled bundle in her hands. The baby girl wrapped inside was weak and hadn’t been bathed for days. I took her in my arms and she smiled. That moment, I knew that I couldn’t leave that place without her.

My husband took care of the formalities, but it wasn’t easy. We couldn’t speak their language and they didn’t speak ours. We had all our official documents in place, but they demanded a hefty “donation”, too. Fights broke out and they simply refused to let us leave without the money. I was terrified and held on to the baby. After seven hours of haggling, we paid them and left with our daughter.

I wanted to leave that place as soon we could. What if they called us back and said that we couldn’t have her? We drove back to Bhubaneshwar and brought her home two days later. Only when I reached Mumbai did I feel that I could take on anything. Our daughter seemed to realise that, too. She looked all around as we reached the city.

We named her Riddhi (a combination of our names, Reeta and Dinesh) and she has been with us for six months now. She is healthier and her grandparents can’t get enough of her. A few official formalities lay pending and Riddhi is not legally ours yet.

We are waiting for a date from the court. I cannot stop thinking that the Orissa organisation can still take her away if they want to.

I tell people my daughter is going to be a linguist. I am a Sindhi and talk to her in Sindhi, my husband in Gujarati and my maid in Telegu. She is very sharp and understands all of us.

She turns one on April 29. I have grand plans — a small birthday party with family members, a big cake, probably, with chocolate frosting and cherries on top, like all those children’s parties I used to attend...

Reeta Prajapati spoke to Radhika Raj

![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani’s daughter Isha Ambani’s firm launches new brand, Reliance’s Rs 8200000000000 company to…

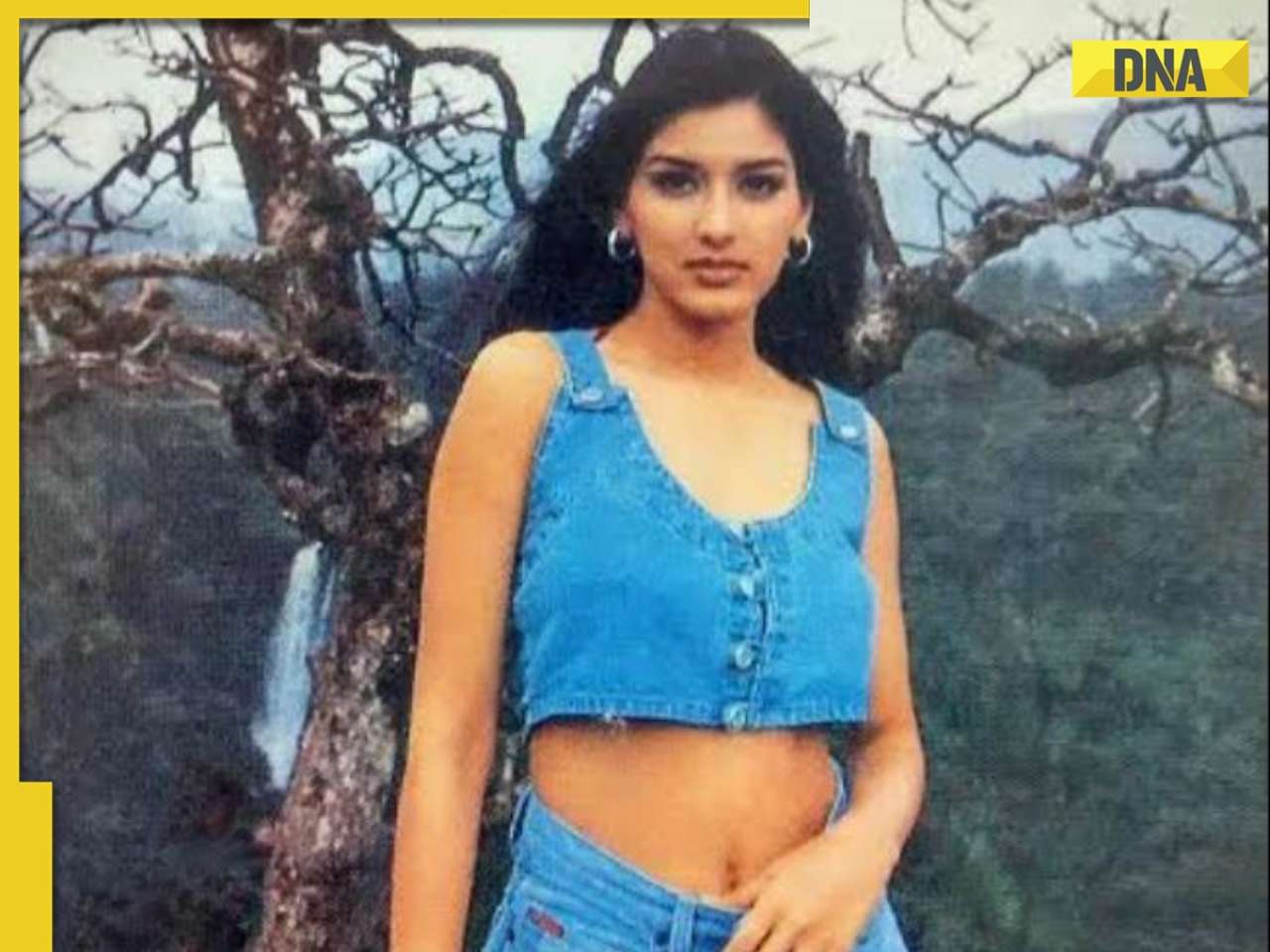

Mukesh Ambani’s daughter Isha Ambani’s firm launches new brand, Reliance’s Rs 8200000000000 company to…![submenu-img]() Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'

Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'![submenu-img]() Heavy rains in UAE again: Dubai flights cancelled, schools and offices shut

Heavy rains in UAE again: Dubai flights cancelled, schools and offices shut![submenu-img]() When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid

When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid![submenu-img]() Gautam Adani’s firm gets Rs 33350000000 from five banks, to use money for…

Gautam Adani’s firm gets Rs 33350000000 from five banks, to use money for…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years

Remember Ayesha Kapur? Michelle from Black, here's how actress, nutrition coach, entrepreneur looks after 19 years![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'

Sonali Bendre says producers called her 'too thin', tried to ‘fatten her up' during the 90s: ‘They'd just tell me...'![submenu-img]() When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid

When 3 Bollywood films with same story released together, two even had same hero, all were hits, one launched star kid![submenu-img]() Salman Khan house firing case: Family of deceased accused claims police 'murdered' him, says ‘He was not the kind…’

Salman Khan house firing case: Family of deceased accused claims police 'murdered' him, says ‘He was not the kind…’![submenu-img]() Meet actor banned by entire Bollywood, was sent to jail for years, fought cancer, earned Rs 3000 crore on comeback

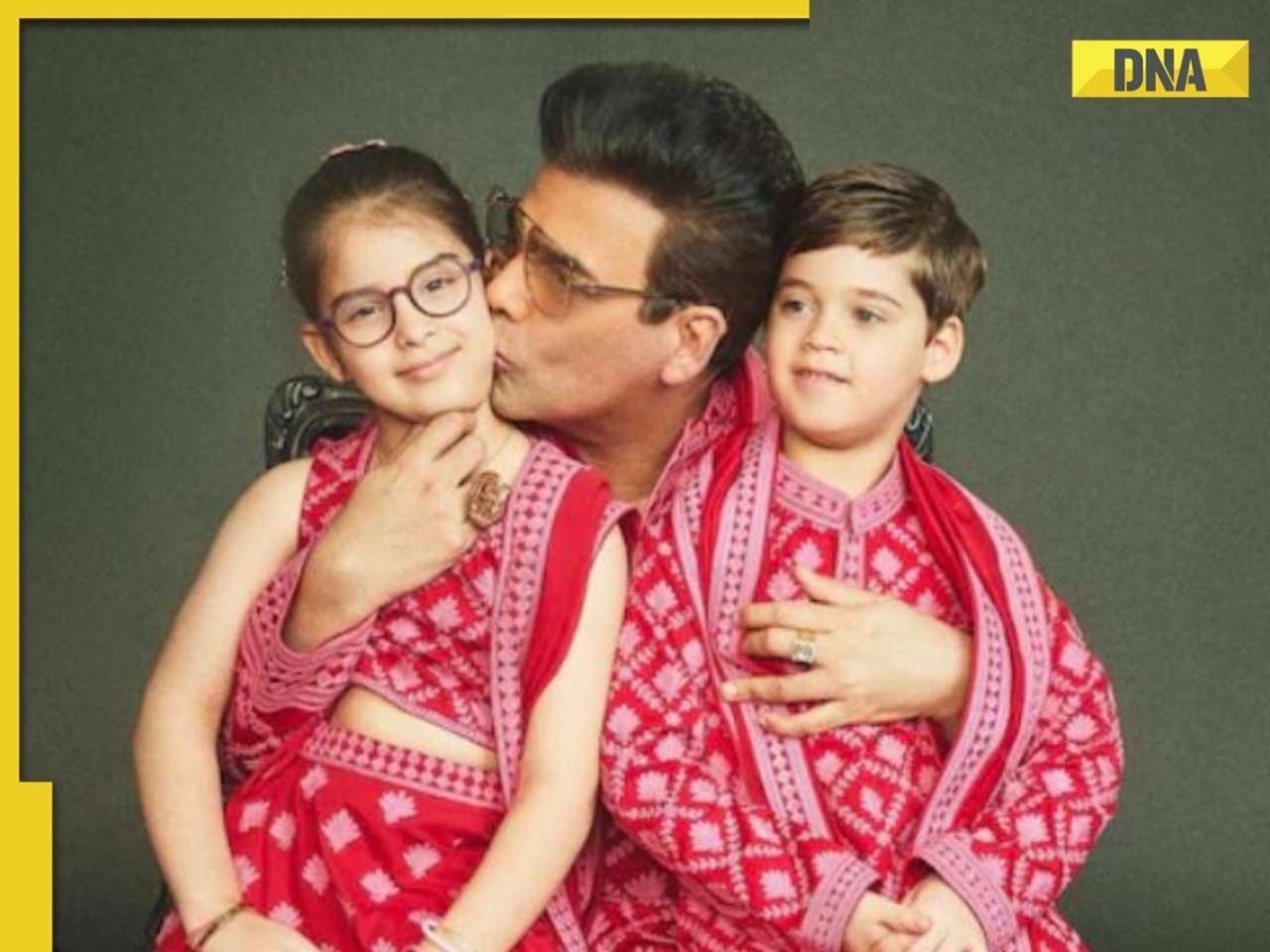

Meet actor banned by entire Bollywood, was sent to jail for years, fought cancer, earned Rs 3000 crore on comeback ![submenu-img]() Karan Johar wants to ‘disinherit’ son Yash after his ‘you don’t deserve anything’ remark: ‘Roohi will…’

Karan Johar wants to ‘disinherit’ son Yash after his ‘you don’t deserve anything’ remark: ‘Roohi will…’![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Bhuvneshwar Kumar's last ball wicket power SRH to 1-run win against RR

IPL 2024: Bhuvneshwar Kumar's last ball wicket power SRH to 1-run win against RR![submenu-img]() BCCI reacts to Rinku Singh’s exclusion from India T20 World Cup 2024 squad, says ‘he has done…’

BCCI reacts to Rinku Singh’s exclusion from India T20 World Cup 2024 squad, says ‘he has done…’![submenu-img]() MI vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

MI vs KKR, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: How can RCB and MI still qualify for playoffs?

IPL 2024: How can RCB and MI still qualify for playoffs?![submenu-img]() MI vs KKR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders

MI vs KKR IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders ![submenu-img]() '25 virgin girls' are part of Kim Jong un's 'pleasure squad', some for sex, some for dancing, some for...

'25 virgin girls' are part of Kim Jong un's 'pleasure squad', some for sex, some for dancing, some for...![submenu-img]() Man dances with horse carrying groom in viral video, internet loves it

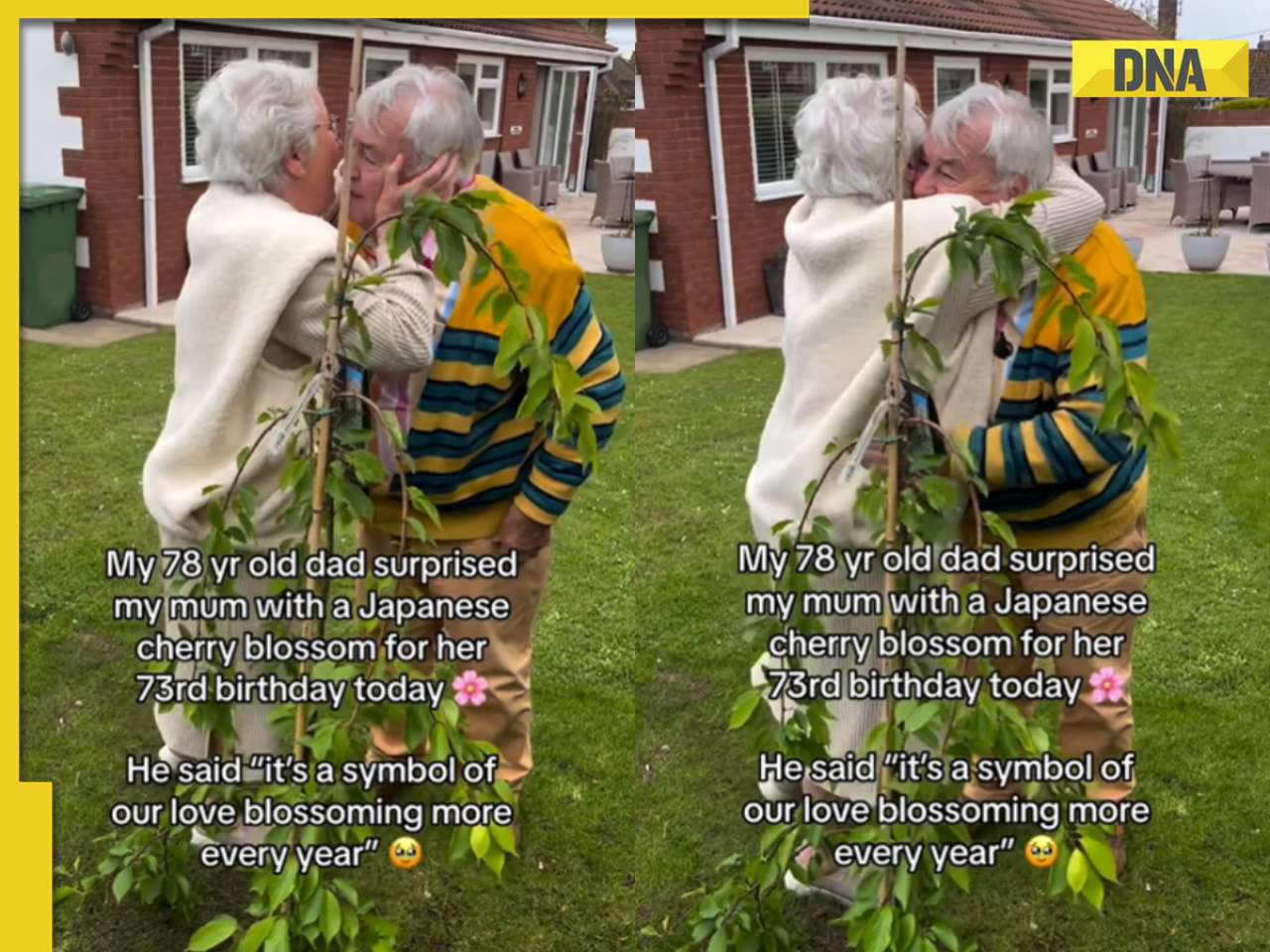

Man dances with horse carrying groom in viral video, internet loves it ![submenu-img]() Viral video: 78-year-old man's heartwarming surprise for wife sparks tears of joy

Viral video: 78-year-old man's heartwarming surprise for wife sparks tears of joy![submenu-img]() Man offers water to thirsty camel in scorching desert, viral video wins hearts

Man offers water to thirsty camel in scorching desert, viral video wins hearts![submenu-img]() Pakistani groom gifts framed picture of former PM Imran Khan to bride, her reaction is now a viral video

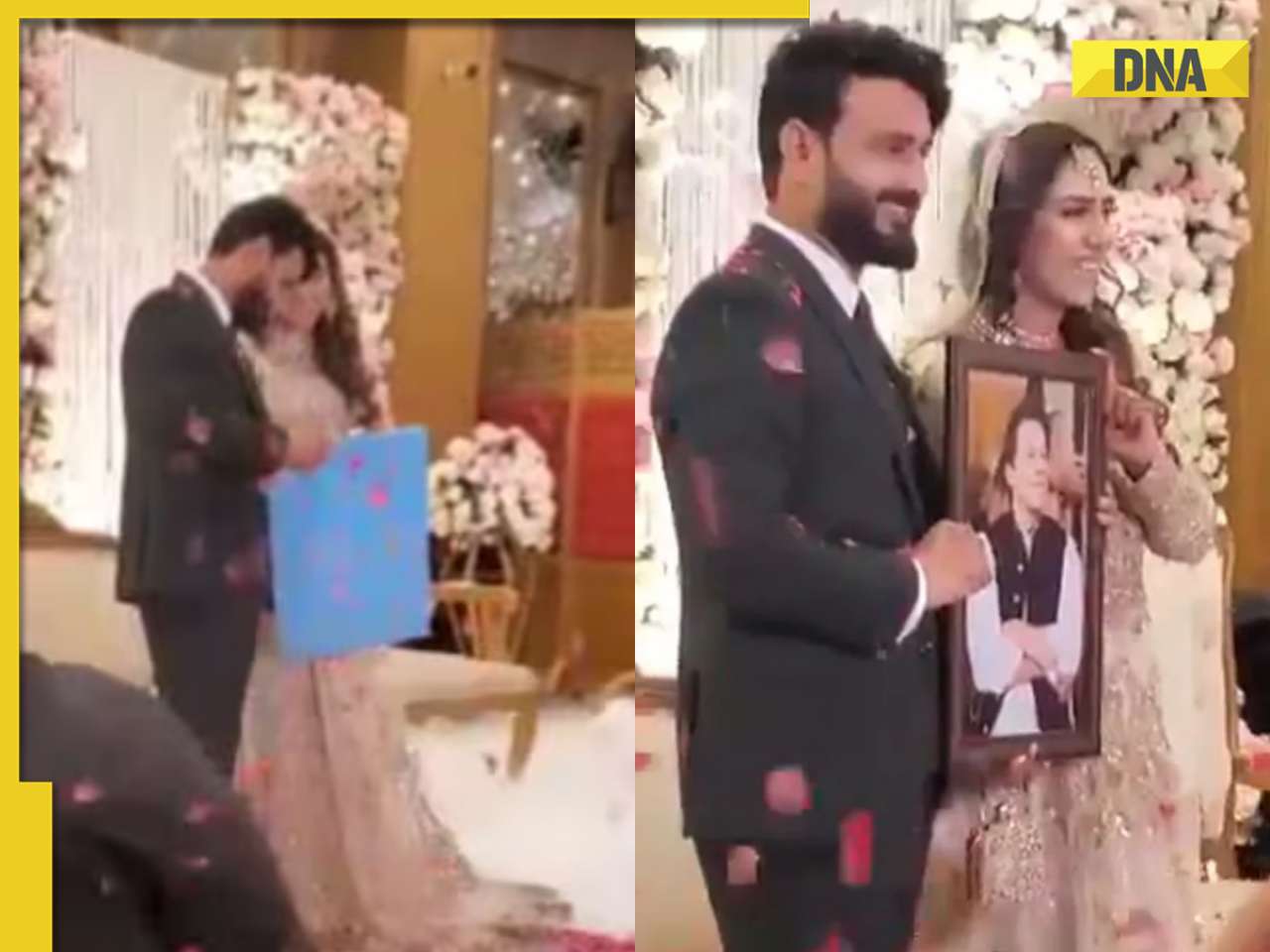

Pakistani groom gifts framed picture of former PM Imran Khan to bride, her reaction is now a viral video

)

)

)

)

)

)