Percy Mistry, author of the expert report on making Mumbai an international financial centre, talks about the report and the controversies surrounding it.

Though he left the country some 44 years ago, a lengthy tenure at the World Bank had brought Percy Mistry in close touch India’s economic whizkids. Among them: Rakesh Mohan, currently deputy governor of the Reserve Bank, and Montek Singh Ahluwalia, deputy chairman of the Planning Commission..

That’s why, when old friend Rakesh Mohan ( then secretary in the department of economic affairs) called - he was enjoying a quiet breakfast with his wife in Italy- he agreed to head the “high-powered expert committee (HPEC)” on making Mumbai an international financial centre.

Unfortunately, the Percy Mistry report has hit the headlines for all the wrong reasons. Not for what it said, but for what was left out of the final report, which Mistry declined to sign.

Among the committee’s major recommendations were to reduce the total public debt to GDP ratio by 75% by the end of fiscal 2007 and shift the burden of future infrastructure financing from public to public-private partnerships (PPPs). It also called on the government of Maharashtra and the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation ( BMC) to appoint a city manager who would be fully accountable for the running of the city, immediate elimination of the 10% limit on corporate ownership of banks, opening up the Indian markets to hedge funds, and a reduction of government holdings in all types of public financial institutions.

All these remain in the final report, but Mistry’s complaint is that half the reasoning is gone. The arguments to support the recommendations were “mangled and diluted to such an extent that Mistry resigned before it was submitted to the ministry of finance. He also denies that he referred to public sector banks as” zombie banks”, as has been reported in segments of the press. All he did was explain the concept with reference to some Japanese banks, but some of committee members obviously personalised the reference.

He still believes the report is a job well done, but is clearly upset by the behaviour of some top functionaries of public financial institutions who were members of the committee. After he tendered his resignation, the report was submitted to the ministry of finance in three days.

Mistry, 60, made his mark in the financial sector quite early. At 26, he was part of the World Bank team that carved out the assets and liabilities of the newly-created Bangladesh, from Pakistan. A Percy Mistry report on how a country could get out of the debt crisis became useful at the time of the south-east Asian debt crisis. Mistry, for a while, led a Hong Kong-based bank that was eventually acquired by Morgan Stanley. When the World Bank called him back, he joined them for 5% of his then salary. Excerpts from an interview with Satish John:

On the reasons for resigning from the committee.

The original arguments and reasoning for the recommendations were provided in a fairly forthright language. This was diluted to a point of senselessness by an extraordinary sense of overdone political sensitivity by a few members. It was not by any means a unanimous view of the committee to dilute the report. It was the view of just a few members. They represented mainly the public sector institutions, and perhaps believed that they were coming in for some unfair criticism for the state the Indian financial system found itself in.

Any notable contribution from any member

It won’t be fair to comment on individual members. You can say that CB Bhave (NSDL) and Ravi Narain (NSE) represented institutions, that were, at one point, public institutions. Their contributions were invaluable. I thought Aditya Puri’s (HDFC bank) contribution was very pragmatic. I think we were five or six members who made a very useful contribution.

Who should take credit for the report as it stands?

Ajay Shah was the leader of my core research team. He and I can claim responsibility for the report. I hate to use the word credit, but certain members of the committee can claim credit for omissions which I believe should not have been made.

What was missing from the final report?

Some comments we had made about the impact of state ownership of financial institutions and what that did in terms of perfectly understandable losses of efficiency and cost-effectiveness, lack of imagination, lack of innovation, lack of competition.

Explanations of those, which were extremely hard hitting, were either diluted or excised.

There were certain things we had to say about the government in Mumbai and political compulsions. Such intrusions which were divisive and communal have diminished the city, and made Bombay less tolerant than it used to be. All that was taken out.

I think it needed to have been said in a forthright fashion. After all, we were not a committee of politicians.

I took the finance minister and chief minister very seriously when they said: “You guys are experts, give us your expert opinion, unvarnished, and we’ll handle the politics.”

After all, we were not writing for the bureaucrats. We were writing for the public.

In hindsight, do you think the trust was misplaced?

I think it’s a fundamental flaw of any committee. My suggestion would be that when a committee is formed, first of all the chairman has to be appointed and he should have a major say on who’s on the committee.

When you put a load of names, either for name recognition or because they are attached to institutions, then you have a problem. They are really not familiar with the content of the subject.

Secondly, I don’t agree that committees such as these should exceed more than seven members. 15 members is just too much.

Thirdly, the notion that the report must be signed by everybody doesn’t lead to democracy. It sometimes leads to blackmail. If one committee member with a particular agenda doesn’t like one sentence, he can hold the whole report to ransom. What really annoyed me was that this report was ready in December 2006. But we were arguing about words. I couldn’t believe that people so senior could be arguing in such a ridiculous fashion. And that’s what led me to take what I call extremely harsh decisive action. If you read the annexe of the report, I resigned on February 7, and the report was passed on February 10. Obviously, it was like a dose of salt.

The resignation wasn’t an impulsive decision on my part. It was very coldly calculated to make sure that the report got to the finance minister in real time. The report was immediately sent. So you can say I resigned for essentially three days.

What went wrong?

Some of the dynamics. When one member who had not attended a single committee meeting decided to take umbrage of some of the language he really didn’t understand - not in English literal terms, but in economic terms what certain expressions meant. I think that sort of created a situation that threatened to unravel the consensus that we had till then. And I really believe that one rule that such committees should apply is that members who never attend a single substantive discussion should never have any say in the final report just because their signatures are supposed to be on them. I am not accustomed to such dealings.

So what happened?

Until the last meeting, I sensed there was complete consensus and we had excellent discussions. But somehow, the meeting in December, seemed to have derailed the process.

Did words such as “zombie banks,” used to describe our financial institutions, cause the problem?

That’s totally untrue by the way. That proves the point that when a lie is repeated often enough, it becomes the truth. “Zombie banks” was not used by me. The only thing that appeared was when we were describing in an explanatory context what happens when you are having a transition from a command control state-dominated economy to a market economy.

As a result of which the state puts in just enough to keep them alive, but not enough to make them thrive. But yet what it puts in, does not let the markets work the way it should that they don’t meet the test of competition and eventually they die.

The term ‘zombie firms’ was coined by a professor at Boston University. He was describing Japan of the 1990s when the country hit a point of stagnation. We were only explaining that. One of the members simply seized on this cap and decided to wear it himself. To me normal committee etiquette will require that if you are a newcomer and that’s his first meeting even though it was the last meeting of the committee then one waits to listen to what others have to say.

It was a canard that came out of a conversation which should never have hit the press. We had taken a self-denying ordinance that except through the convener, no member should talk to the media before the report was published.

It was some PSU bankers who decided to call themselves zombie banks and then stick it on me. (laughs).

I suppose this was a genuine misunderstanding. But a member who doesn’t attend any of the substantial discussions and comes to the last meeting and suddenly takes a shoo at things when he wasn’t a part of the discussion.

But then why did you have to resign?

As an intellectual purist my sensibilities have been offended by having the crux of well made arguments damaged simply by omitting large parts of them which were considered sensitive.

In hindsight do you regret to have been involved in the committee?

None, whatsoever. We have done a job that we should be proud of. My response is that I am not a dreamer. I think my driving force has been to do what’s right and if possible to give other people the credit. In this case, more of the credit belongs to Ajay than to me.

In terms of thinking, content between the two of us, we really did talk this through. He (Ajay) chucked the first draft at me and I chucked the second draft at him. This is how it happened. I think the report must be owned by India and by the ministry of finance. And it’s now up to them to very seriously discuss the report in a variety of fora.

It’s the demand of industry and banks to make Mumbai a financial centre. The regulators may see it as criticism. But our regulators are extremely adept and astute to manage change.

If you have an institution which is omnipotent, omnipresent and omniscient in the financial system, where state-owned banks are its children, in the brave new world, such a system no longer works. I hope to see that the RBI is big enough and far-sighted enough to adapt itself to the kind of change that India needs.

I think it’s one of the greatest institutions in India and the world. I’ve the greatest respect for RBI. Governor YV Reddy, and deputy governor Rakesh Mohan are my personal friends.

I think a lot of people who have grown up in the RBI system need to change.

You can increasingly see monetary authorities becoming increasingly specialised. Even the Federal Reserve is feeling this and focusing exclusively on monetary policy and inflation targeting.

But RBI has transferred its stake in the State Bank to the government. They are doing things now..

At the moment it’s only game play. It’s the state of India which is the owner of both (SBI and RBI). I think we missed a tremendous opportunity. I ask myself if I know what the political economy constraints are. Recently, ICBC of China made a massive floatation in the capital markets. They even allowed a strategic foreign investor. If China could do it, we could do it too and in the process raise a enormous amount of resources. It’s an enormous opportunity missed. ICICI Bank and HDFC Bank are largely owned by foreign institutions. Those foreign institutions don’t interfere in their management.

I would like that thinking to apply to the entire banking system, the entire insurance industry and to the entire asset management industry. In this day and age, the nationality of ownership really doesn’t matter what matters is management control and global competitiveness.

But aren’t the barriers opening up here?

There are constraints to manage foreign funds in India. In this business we could be leading the world ourselves. There’s no excuse, whatever, the legacy issues are. We turned the real sector around in just 12 years. We could change the financial system around in a space of five years.

Can SEZs solve the problem. Can they create an international finance centre?

SEZs will complicate the issue. This approach essentially admits defeat. You can’t change the country as there are too many vested interests, opposing changes in fundamental laws such as labour laws, taxation laws, financial laws. It’s too much of an hassle. Therefore, we’ll create one class where essentially the sovereignty and those laws don’t apply. We have taken an approach which has never been tried anywhere elsewhere. We have taken an approach where we are setting up hundreds SEZs as opposed to what other nations that have earmarked four or five very large areas. The entire state of Goa, city areas of Mumbai, Pune and Nashik, which are contiguous, should be earmarked as an SEZ, so that urban planning is better planned.

Imagine what this kind of a move can do for roads, sewerage systems, irrigation, water supply, power etc. It’s far more intelligent then giving away 500 hectares here and 5,000 hectares there. This whole policy is profoundly and fundamentally misconceived. I think there will be major problems in what I call regulatory arbitrage between the so-called territory of an SEZ and India and we have not conceptualised it right. Look at China; they went ahead to develop whole cities like Macau, Shenzhen. Having 300-400 SEZs will overstretch our administrative capacities. But we have argued powerfully against SEZs. Because India is not like Dubai or Mauritius, or even Singapore. India is more like United States and European Union. We had complete unanimity in the committee that SEZ is not an alternative. The story now is that IIFC should happen.

What’s wrong with the current system?

The structure of financial services industry is so cluttered up with dinosaurs who see ‘a change in direction’ as threatening. This is not conducive for rapid movement down this road. Further, the regulators are chary of the change and they’ll be arguing for gradualism more for the sake of gradualism and not because it’s right for India . There are times when you have to just throw the door open. Opening one inch at a time will not work.

![submenu-img]() This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...

This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...![submenu-img]() Virat Kohli’s new haircut ahead of RCB vs CSK IPL 2024 showdown sets internet on fire, see here

Virat Kohli’s new haircut ahead of RCB vs CSK IPL 2024 showdown sets internet on fire, see here![submenu-img]() BCCI bans Mumbai Indians skipper Hardik Pandya, slaps INR 30 lakh fine for....

BCCI bans Mumbai Indians skipper Hardik Pandya, slaps INR 30 lakh fine for....![submenu-img]() 'Justice must prevail': Former PM HD Deve Gowda breaks silence in Prajwal Revanna case

'Justice must prevail': Former PM HD Deve Gowda breaks silence in Prajwal Revanna case![submenu-img]() India urges students in Kyrgyzstan to stay indoors amid violent protests in Bishkek

India urges students in Kyrgyzstan to stay indoors amid violent protests in Bishkek![submenu-img]() Meet IIT graduates, three friends who were featured in Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia list, built AI startup, now…

Meet IIT graduates, three friends who were featured in Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia list, built AI startup, now…![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC in fourth attempt to become IAS officer, secured AIR...

Meet woman who cracked UPSC in fourth attempt to become IAS officer, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet IIT JEE 2024 all-India girls topper who scored 100 percentile; her rank is…

Meet IIT JEE 2024 all-India girls topper who scored 100 percentile; her rank is…![submenu-img]() Meet PhD wife of IIT graduate hired at Rs 100 crore salary package, was fired within a year, he is now…

Meet PhD wife of IIT graduate hired at Rs 100 crore salary package, was fired within a year, he is now…![submenu-img]() Meet woman not from IIT, IIM or NIT, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt with AIR...

Meet woman not from IIT, IIM or NIT, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt with AIR...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera

Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera![submenu-img]() Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’

Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Madgaon Express, Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, Bridgerton season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Madgaon Express, Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, Bridgerton season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Sunanda Sharma exudes royalty as she debuts at Cannes Film Festival in anarkali, calls it ‘Punjabi community's victory’

Sunanda Sharma exudes royalty as she debuts at Cannes Film Festival in anarkali, calls it ‘Punjabi community's victory’![submenu-img]() Aishwarya Rai walks Cannes red carpet in bizarre gown made of confetti, fans say 'is this the Met Gala'

Aishwarya Rai walks Cannes red carpet in bizarre gown made of confetti, fans say 'is this the Met Gala'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...

This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...![submenu-img]() This film had 3 superstars, was unofficial remake of Hollywood classic, was box office flop, later became hit on...

This film had 3 superstars, was unofficial remake of Hollywood classic, was box office flop, later became hit on...![submenu-img]() Meet Nancy Tyagi, Indian influencer who wore self-stitched gown weighing over 20 kg to Cannes red carpet

Meet Nancy Tyagi, Indian influencer who wore self-stitched gown weighing over 20 kg to Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Telugu actor Chandrakanth found dead days after rumoured girlfriend Pavithra Jayaram's death in car accident

Telugu actor Chandrakanth found dead days after rumoured girlfriend Pavithra Jayaram's death in car accident![submenu-img]() Meet superstar who faced casting couch at young age, worked in B-grade films, was once highest-paid actress, now..

Meet superstar who faced casting couch at young age, worked in B-grade films, was once highest-paid actress, now..![submenu-img]() Viral video: Flood-rescued dog comforts stranded pooch with heartfelt hug, internet hearts it

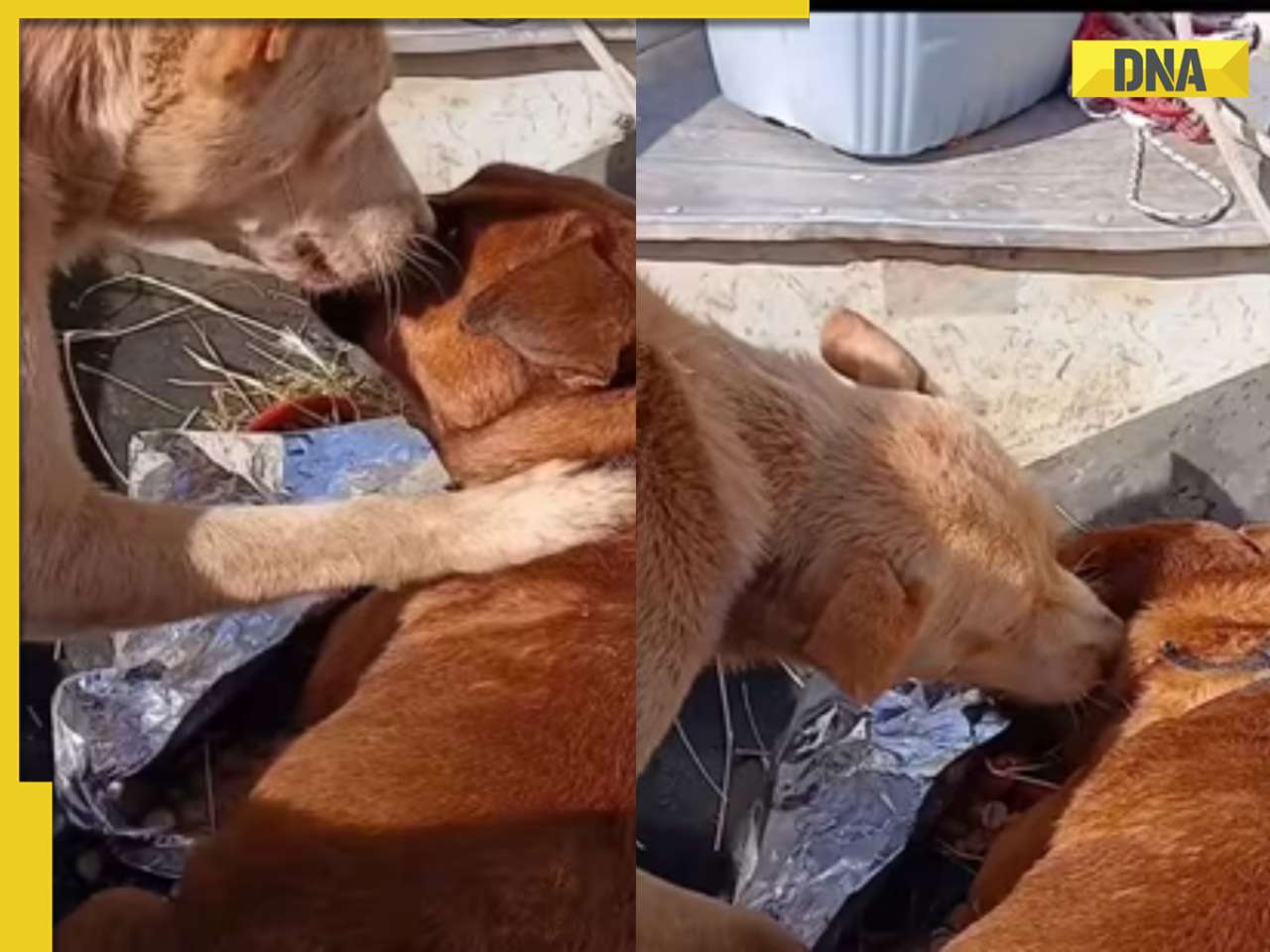

Viral video: Flood-rescued dog comforts stranded pooch with heartfelt hug, internet hearts it![submenu-img]() Dubai ruler captured walking hand-in-hand with grandson in viral video, internet can't help but go aww

Dubai ruler captured walking hand-in-hand with grandson in viral video, internet can't help but go aww![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Virat Kohli drops massive hint on MS Dhoni’s retirement plan ahead of RCB vs CSK clash

IPL 2024: Virat Kohli drops massive hint on MS Dhoni’s retirement plan ahead of RCB vs CSK clash![submenu-img]() Do you know which God Parsis worship? Find out here

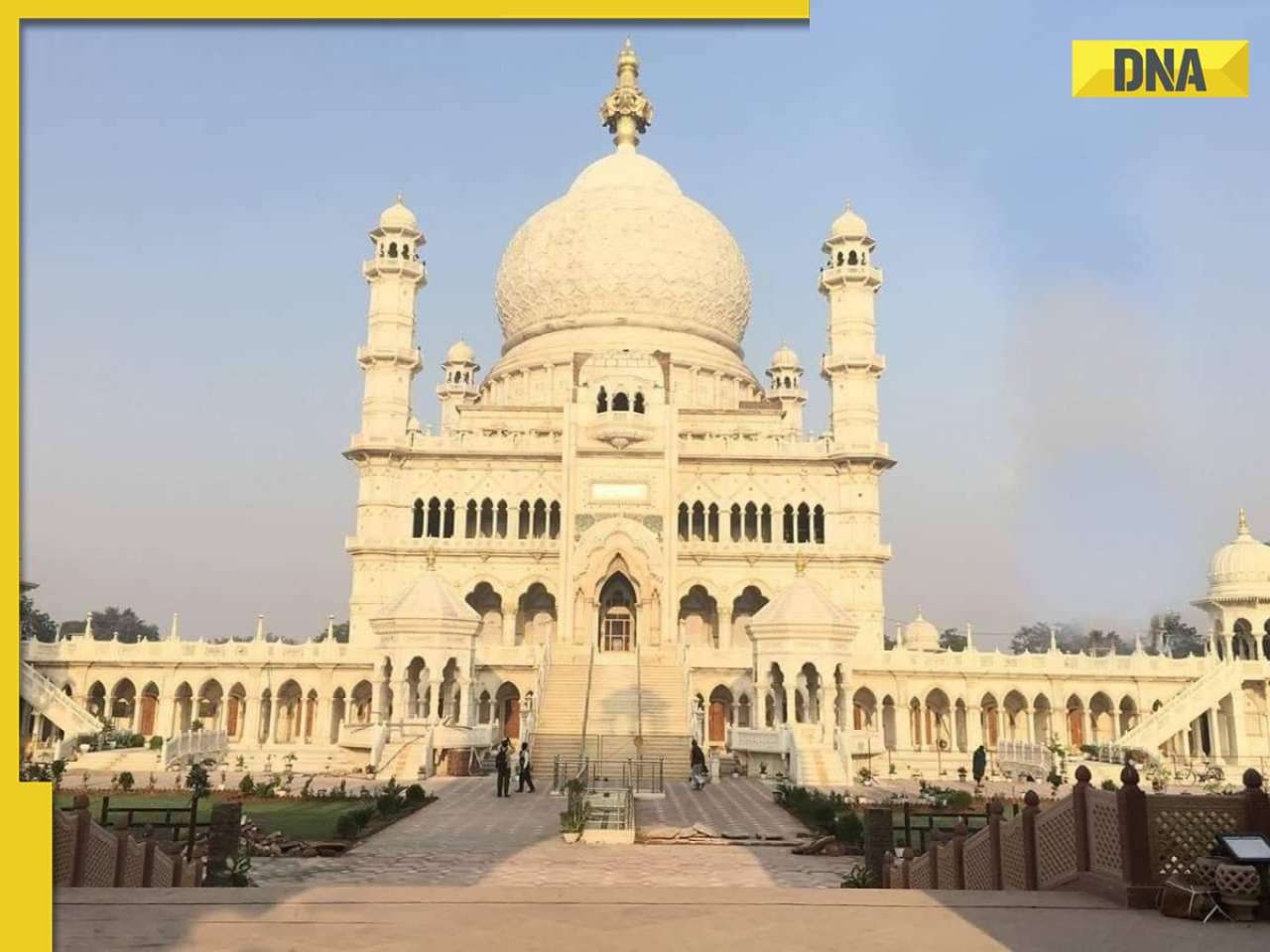

Do you know which God Parsis worship? Find out here![submenu-img]() This white marble structure in Agra, competing with Taj Mahal, took 104 years to complete

This white marble structure in Agra, competing with Taj Mahal, took 104 years to complete

)

)

)

)

)

)

)