Subuhi Jiwani casts off middle-class propriety to go and watch the Bhojpuri mythological, Behula, at Sheetal theatre in Kurla, and comes away with a holistic cinematic experience no multiplex can ever offer.

Subuhi Jiwani casts off middle-class propriety to go and watch the Bhojpuri mythological, Behula, at Sheetal theatre in Kurla, and comes away with a holistic cinematic experience no multiplex can ever offer.

Dress modestly, he said. We were going to see Behula, a Bhojpuri mythological, at Sheetal theatre in Kurla. I had translated ‘modestly’ as a traditional, covering garment and landed up in a crisp cotton salwar kameez. He had meant, “wear old clothes, faded ones.”

When we arrived, all the colours were faded — the theatre’s outer facade, the shirts of the men, their faces — and my bright green and white made me a badly done superimposition. Colour discordance was only a symptom of class discordance; this was undoubtedly a form of tourism. I refused to be swallowed up by my middle class guilt, however.

A sizable crowd of young men had lined up to get into the theatre. I stepped towards the counter; a path cleared like it does in the general compartment of a local. I was ‘ladies’ and had privileges like cutting the line. I did with only a twinge of guilt.

We walked up the stairs through the bland, gray interiors, towards the balcony. We had stepped into Bombay of the 1970s, said my friend. More than a period piece, here was an image of a place ‘good girls’ didn’t visit — with or without male friends. But I’d wanted to leave behind middle class propriety. It was time to live and breathe, however momentarily, a working class space, to sit amidst a ‘lumpen audience’, to see another Bombay.

An olfactory attack awaited us on the mezzanine. The smell of spat out paan hung over the balcony with the vengeance of an itch that can’t be scratched. The air sat thick and metal snakes with dysfunctional AC vents crawled up the sides of the theatre. Three fans tried desperately to offer relief when none was in sight. The heat was inescapable, our kismat.

The seats may have been cramped and hard but you could fling your feet over the row in front of you. Shuffling in your seat sometimes meant that the seats themselves shuffled. I tried not to think of the diverse array of creatures living their entire lives in these seats.

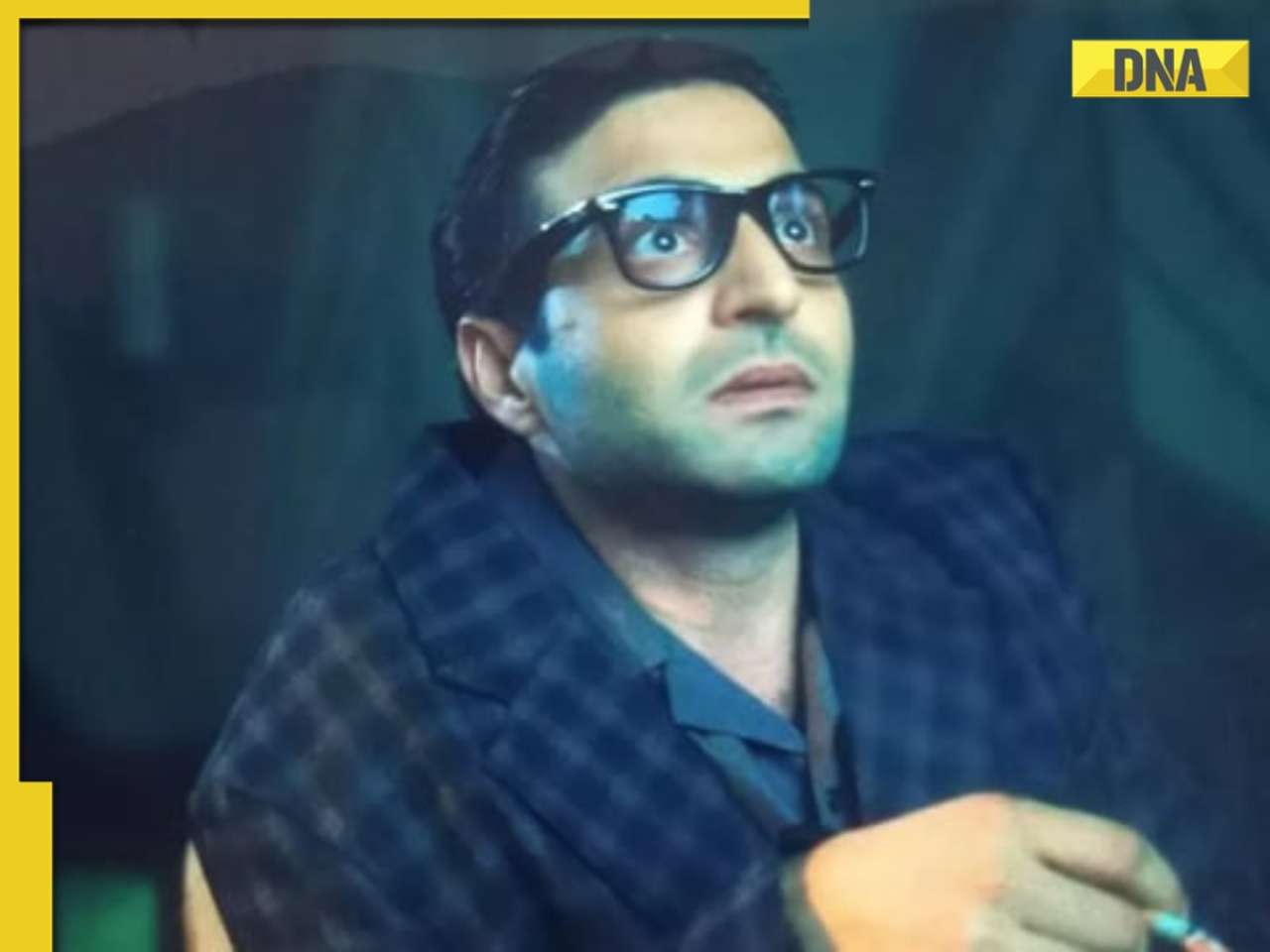

We settled in, my dupatta a temporary fan, and to our pleasure, the projectionist skipped the national anthem, going straight for the feature. The theatre lights still on, a dim image of blue-faced Hema Malini appeared; the shadow of a ceiling fan fell across the image. When miffed spectators in the stalls let out guttural shouts of dissatisfaction, the lights dimmed, only to reveal a projector with a weak lamp.

“Purane jamane ka projector hai,” said my friend. A projector of older times and a print that had lived a long life. Scratches ran across the length of the film but we weren’t the only ones complaining. Come a night shot, the scratches stood out against the black of night and the same shouts arose from the stalls. The narrative in popular film may be all-consuming, but the audience demands good form too.

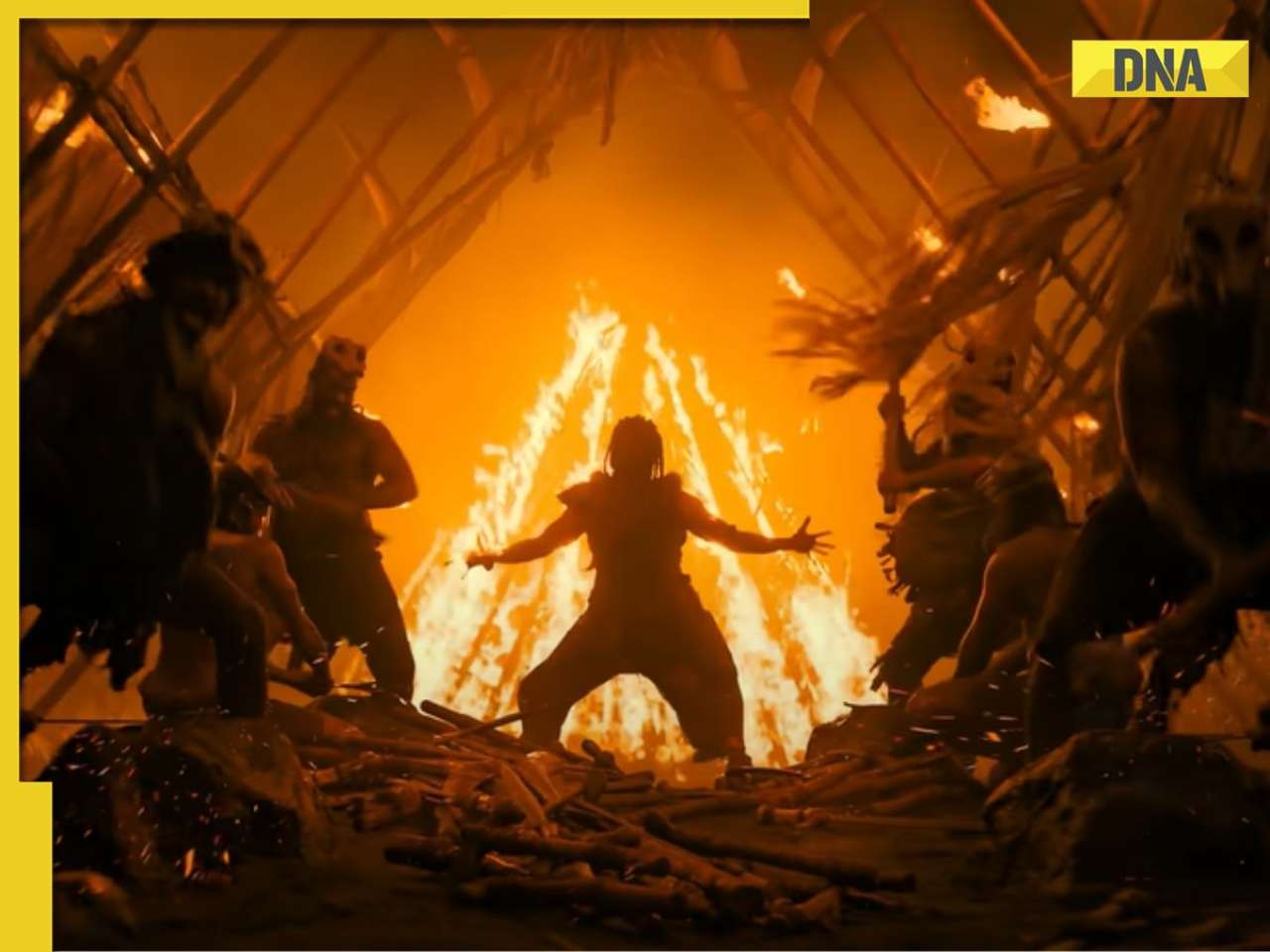

Yet, all-consuming it was. Kali stomped the earth during the opening credits, her shivering palm and outstretched fingers dashed towards us like lightning. Maa was telling us who was in charge and we were doing her darshan. Then began the story within the story within the story, one segueing into another through flashbacks.

The kernel revolved around the appeasement of goddess Mansa, who has the power to cure infectious diseases and reverse the venomous impact of snakebite. Originally an adivasi goddess, Mansa had to fight to become a part of the Hindu pantheon. On putting this desire before her father Shiva, she was asked by him to convince King Chand of Anga to worship her. She did, after much tribulation.

Behula takes up this mythic tale and weaves into it a human dimension: tantriks, occult kings, and suffering, dutiful wives eager to rescue their husbands from disability and death. In a final scene that seals Maa’s powers and Mansa’s ascendence, a sutradharini prays to the goddess at a temple, the bells moving frantically, the beats hectic. Her husband, who she has pulled on a hand-drawn cart all through the film, now begins to walk. Maa ka ashirvaad hai. A popular film, even a mythological, is perhaps incomplete without an item number. When it came on, there was the expected hooting and hollering from the aisles in response to suggestive lower-lip-biting on screen. It was more subdued than I had imagined and the film, less bawdy.

I’ll remember Behula not for its spectacular narrative or intermeshing of the real and the mythological, but for an aroused sensorium. The shockingly loud ring tones heard and the even louder conversations had. Stale popcorn sold in orange packets, which we’d relished as children and ate again here with nostalgia. The film’s idiosyncratic switch from Super 35mm to video and back, the colours jumping wildly across the spectrum.

The lights switching on before the film was over. And the stubborn insistence on sitting through what Phalke had called ‘pardyacha natak’, theatre on the curtain, and around it.

All this despite the heat, the sweat, the smell.

![submenu-img]() This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...

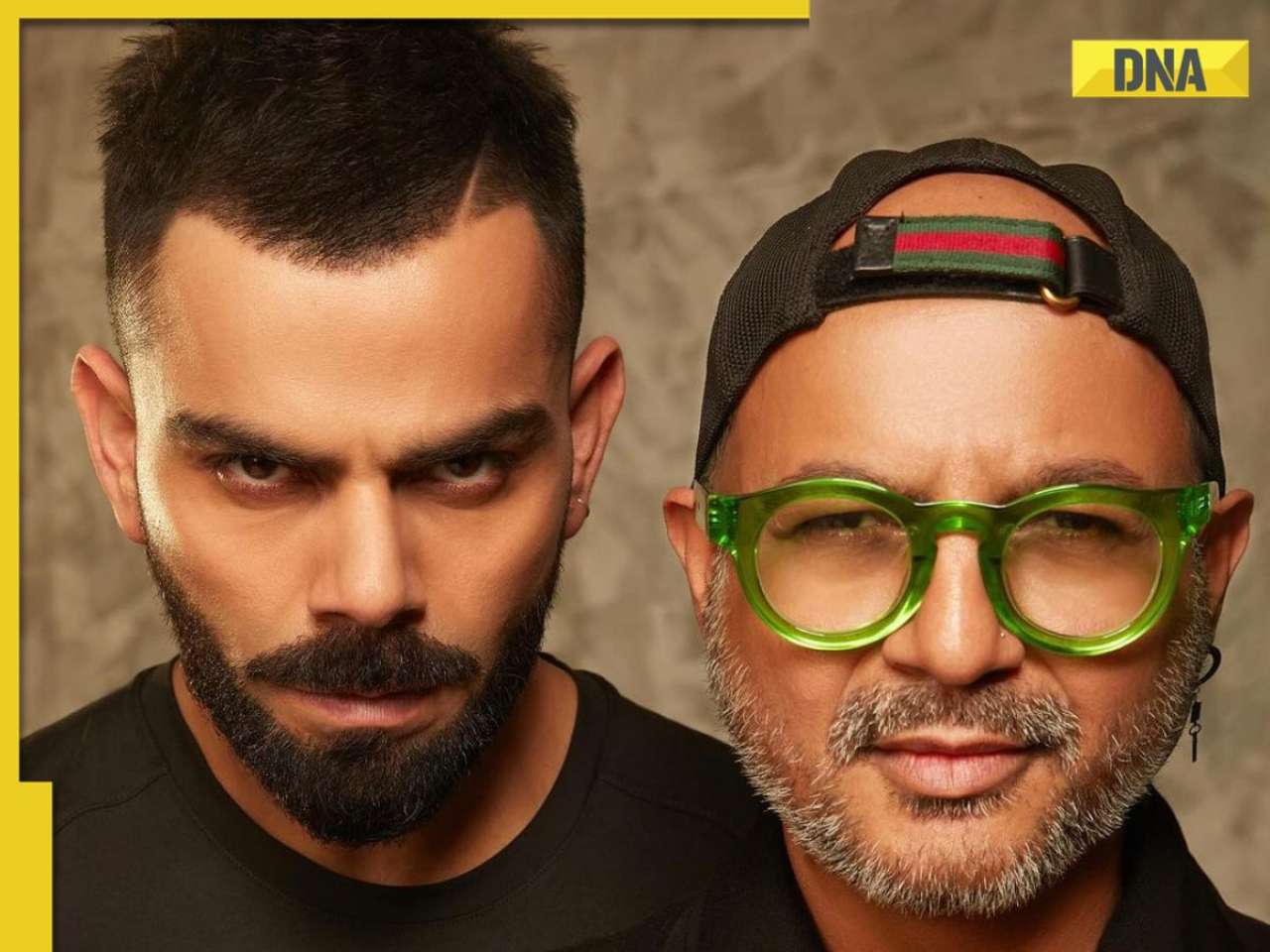

This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...![submenu-img]() Virat Kohli’s new haircut ahead of RCB vs CSK IPL 2024 showdown sets internet on fire, see here

Virat Kohli’s new haircut ahead of RCB vs CSK IPL 2024 showdown sets internet on fire, see here![submenu-img]() BCCI bans Mumbai Indians skipper Hardik Pandya, slaps INR 30 lakh fine for....

BCCI bans Mumbai Indians skipper Hardik Pandya, slaps INR 30 lakh fine for....![submenu-img]() 'Justice must prevail': Former PM HD Deve Gowda breaks silence in Prajwal Revanna case

'Justice must prevail': Former PM HD Deve Gowda breaks silence in Prajwal Revanna case![submenu-img]() India urges students in Kyrgyzstan to stay indoors amid violent protests in Bishkek

India urges students in Kyrgyzstan to stay indoors amid violent protests in Bishkek![submenu-img]() Meet IIT graduates, three friends who were featured in Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia list, built AI startup, now…

Meet IIT graduates, three friends who were featured in Forbes 30 Under 30 Asia list, built AI startup, now…![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC in fourth attempt to become IAS officer, secured AIR...

Meet woman who cracked UPSC in fourth attempt to become IAS officer, secured AIR...![submenu-img]() Meet IIT JEE 2024 all-India girls topper who scored 100 percentile; her rank is…

Meet IIT JEE 2024 all-India girls topper who scored 100 percentile; her rank is…![submenu-img]() Meet PhD wife of IIT graduate hired at Rs 100 crore salary package, was fired within a year, he is now…

Meet PhD wife of IIT graduate hired at Rs 100 crore salary package, was fired within a year, he is now…![submenu-img]() Meet woman not from IIT, IIM or NIT, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt with AIR...

Meet woman not from IIT, IIM or NIT, cracked UPSC exam in first attempt with AIR...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera

Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera![submenu-img]() Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’

Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Madgaon Express, Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, Bridgerton season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Madgaon Express, Zara Hatke Zara Bachke, Bridgerton season 3, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Sunanda Sharma exudes royalty as she debuts at Cannes Film Festival in anarkali, calls it ‘Punjabi community's victory’

Sunanda Sharma exudes royalty as she debuts at Cannes Film Festival in anarkali, calls it ‘Punjabi community's victory’![submenu-img]() Aishwarya Rai walks Cannes red carpet in bizarre gown made of confetti, fans say 'is this the Met Gala'

Aishwarya Rai walks Cannes red carpet in bizarre gown made of confetti, fans say 'is this the Met Gala'![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...

This singer helped BCCI when it had no money to award 1983 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team, raised 20 lakh by...![submenu-img]() This film had 3 superstars, was unofficial remake of Hollywood classic, was box office flop, later became hit on...

This film had 3 superstars, was unofficial remake of Hollywood classic, was box office flop, later became hit on...![submenu-img]() Meet Nancy Tyagi, Indian influencer who wore self-stitched gown weighing over 20 kg to Cannes red carpet

Meet Nancy Tyagi, Indian influencer who wore self-stitched gown weighing over 20 kg to Cannes red carpet![submenu-img]() Telugu actor Chandrakanth found dead days after rumoured girlfriend Pavithra Jayaram's death in car accident

Telugu actor Chandrakanth found dead days after rumoured girlfriend Pavithra Jayaram's death in car accident![submenu-img]() Meet superstar who faced casting couch at young age, worked in B-grade films, was once highest-paid actress, now..

Meet superstar who faced casting couch at young age, worked in B-grade films, was once highest-paid actress, now..![submenu-img]() Viral video: Flood-rescued dog comforts stranded pooch with heartfelt hug, internet hearts it

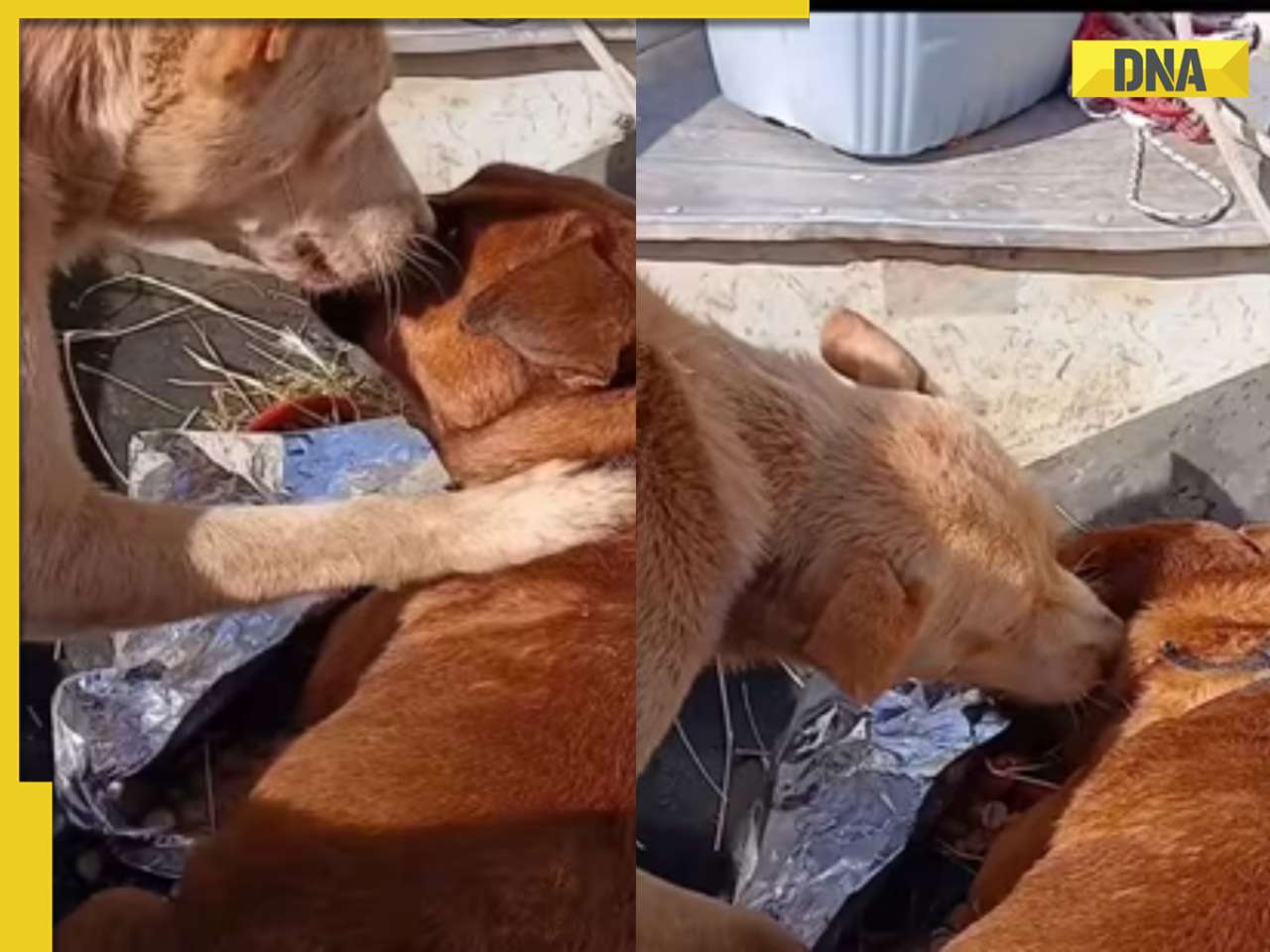

Viral video: Flood-rescued dog comforts stranded pooch with heartfelt hug, internet hearts it![submenu-img]() Dubai ruler captured walking hand-in-hand with grandson in viral video, internet can't help but go aww

Dubai ruler captured walking hand-in-hand with grandson in viral video, internet can't help but go aww![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Virat Kohli drops massive hint on MS Dhoni’s retirement plan ahead of RCB vs CSK clash

IPL 2024: Virat Kohli drops massive hint on MS Dhoni’s retirement plan ahead of RCB vs CSK clash![submenu-img]() Do you know which God Parsis worship? Find out here

Do you know which God Parsis worship? Find out here![submenu-img]() This white marble structure in Agra, competing with Taj Mahal, took 104 years to complete

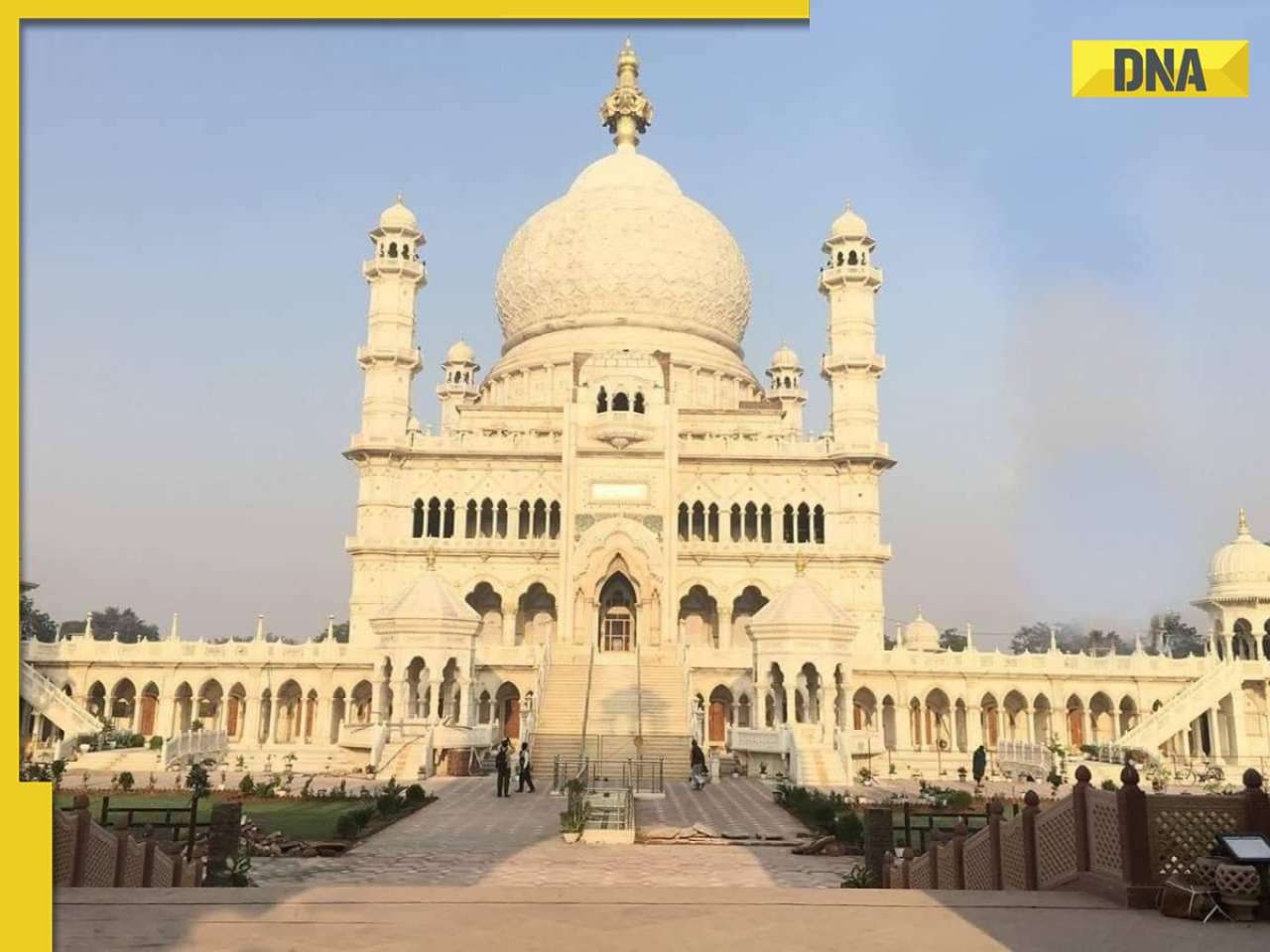

This white marble structure in Agra, competing with Taj Mahal, took 104 years to complete

)

)

)

)

)

)