Book: Empire Of The Moghul: Ruler Of The World

Author: Alex Rutherford

Hachette

402 pages

Rs495

Akbar is considered the greatest Mughal emperor. But the best men have their flaws. The third installment of the Empire Of The Moghul series, Ruler Of The World, does a great job of portraying both the strengths and weaknesses of Akbar, but falls short of explaining why these flaws existed.

The first half of the book describes Akbar’s early campaigns. From defeating Hemu of the Suri dynasty barely 10 months after ascending the throne at the age of 14, to the quelling of the Shah Daud rebellion in faraway Bengal in, you see how Akbar develops as a warrior, a strategist and an emperor. And then those very qualities draw him apart from his eldest son, Salim (Jehangir).

For example, Akbar starts participating in war councils when he is barely a teenager. His experiences make him a decisive leader. He expects his son to be the same. On one occasion, when he has invited Jesuit priests to his court, he asks the young Salim what he thinks of them.

When Salim fumbles, Akbar responds, “You must have some opinion... After all, why did you come to see the priests?” His father’s legacy weighs heavily upon Salim and Akbar’s high expectation only makes him more awkward.

The second half of the book deals entirely with the father-son relationship, and is written from Salim’s point-of-view. Akbar comes across as a father who underestimates his son’s capabilities.

For instance, Akbar grasps the importance of Babur’s words: ‘War and booty keep men true... Be generous to your supporters. If they know they have more to gain from you than from anyone else they will stay loyal.”

Yet, he denies his son the same opportunity when he refuses to let him participate in war councils and denies him governorship of provinces. His unilateral decision to bring up Salim’s youngest son Khurram (who later takes the title ‘Shah Jahan’) plants a doubt in Salim’s mind that his father might choose his grandsons over him as emperor.

While narrating the story from Salim’s point-of-view does turn the focus on the mistakes Akbar made, it does little to explain why a great emperor would alienate his successor and put the future of the empire in jeopardy. This makes an otherwise great book less than satisfying.

Salim is the hero of the second half. While his actions do insult and hurt Akbar — sleeping with Anarkali, Akbar’s favourite concubine, drinking opium, or killing Abu Fazl, Akbar’s confidante — you empathise with Salim, who, despite everything else, continues to love his father. Akbar finally does choose Salim as his successor.

But his actions have planted the seed of ambition in his grandson, Salim’s first son, Khusrau, who rebels soon after Akbar’s death. It’s a racy end and sets the stage for the fourth book of this series.

![submenu-img]() Viral video: Python escapes unscathed after fierce assault by aggressive mongoose gang, watch

Viral video: Python escapes unscathed after fierce assault by aggressive mongoose gang, watch![submenu-img]() Google banned over 2200000 apps from Play Store, removed 333000 bad accounts for…

Google banned over 2200000 apps from Play Store, removed 333000 bad accounts for…![submenu-img]() Once one of Bollywood's top heroines, this actress was slammed for kissing King Charles, ran from home, now she...

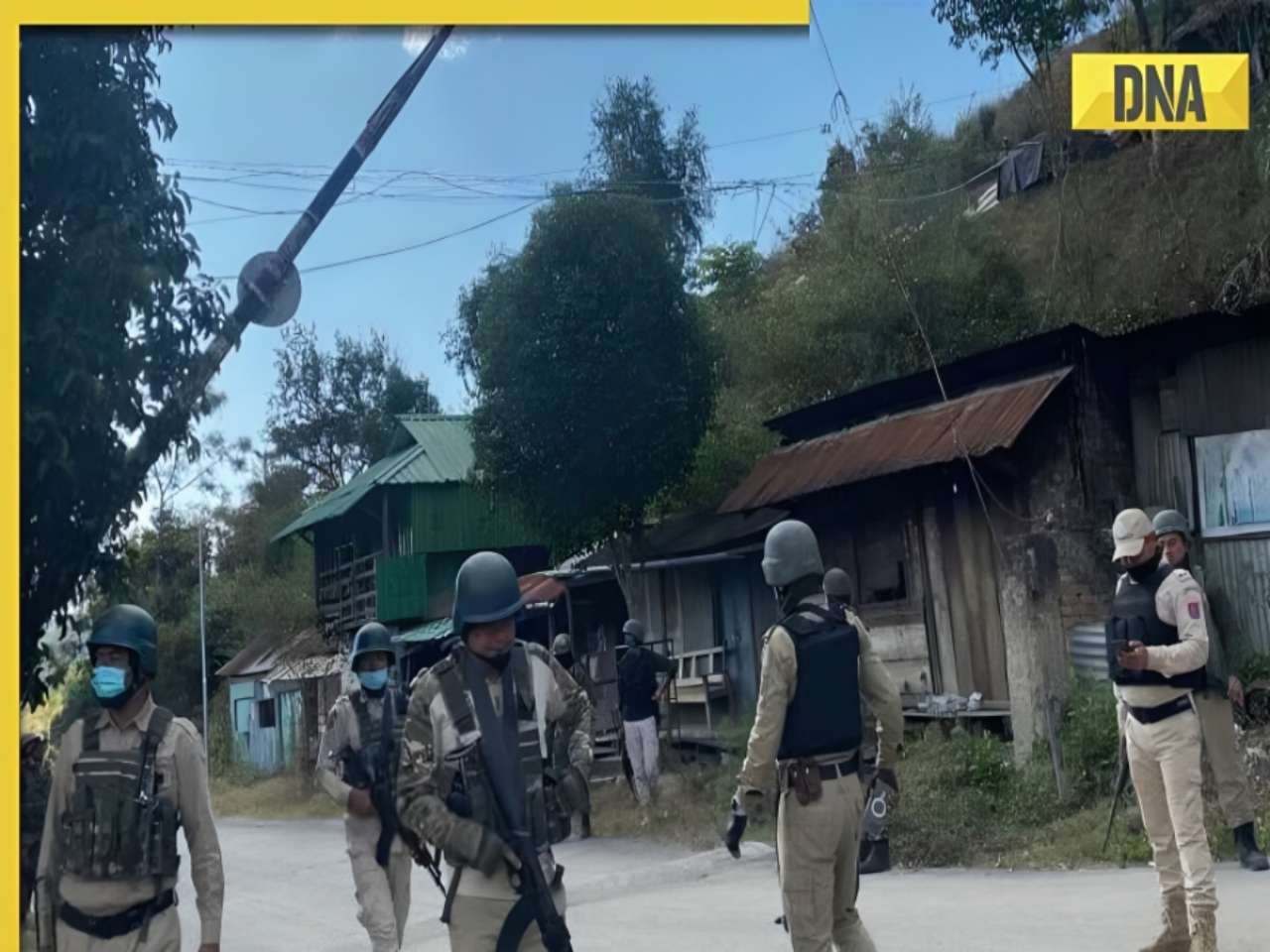

Once one of Bollywood's top heroines, this actress was slammed for kissing King Charles, ran from home, now she...![submenu-img]() Manipur Police personnel drove 2 Kuki women to mob that paraded them naked: CBI charge sheet

Manipur Police personnel drove 2 Kuki women to mob that paraded them naked: CBI charge sheet ![submenu-img]() Makarand Deshpande reveals reason behind Monkey Man’s delayed India release: ‘I feel because of…’

Makarand Deshpande reveals reason behind Monkey Man’s delayed India release: ‘I feel because of…’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Once one of Bollywood's top heroines, this actress was slammed for kissing King Charles, ran from home, now she...

Once one of Bollywood's top heroines, this actress was slammed for kissing King Charles, ran from home, now she...![submenu-img]() Makarand Deshpande reveals reason behind Monkey Man’s delayed India release: ‘I feel because of…’

Makarand Deshpande reveals reason behind Monkey Man’s delayed India release: ‘I feel because of…’![submenu-img]() Meet actor, beaten up in school, failed police entrance exam, lived in garage, worked as driver, now worth Rs 650 crore

Meet actor, beaten up in school, failed police entrance exam, lived in garage, worked as driver, now worth Rs 650 crore![submenu-img]() Harman Baweja and wife Sasha Ramchandani blessed with a baby girl: Report

Harman Baweja and wife Sasha Ramchandani blessed with a baby girl: Report![submenu-img]() Parineeti Chopra says she didn't even know if Raghav Chadha was married, had children when she decided to marry him

Parineeti Chopra says she didn't even know if Raghav Chadha was married, had children when she decided to marry him![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians

IPL 2024: Marcus Stoinis, Mohsin Khan power Lucknow Super Giants to 4-wicket win over Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() 'Horrifying, hope he keeps...': KKR co-owner Shahrukh Khan on Rishabh Pant's life-threatening car accident

'Horrifying, hope he keeps...': KKR co-owner Shahrukh Khan on Rishabh Pant's life-threatening car accident![submenu-img]() CSK vs PBKS, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs PBKS, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() CSK vs PBKS IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Chennai Super Kings vs Punjab Kings

CSK vs PBKS IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Chennai Super Kings vs Punjab Kings![submenu-img]() KKR's Harshit Rana fined 100 per cent of his match fees, handed 1-match ban for....

KKR's Harshit Rana fined 100 per cent of his match fees, handed 1-match ban for....![submenu-img]() Viral video: Python escapes unscathed after fierce assault by aggressive mongoose gang, watch

Viral video: Python escapes unscathed after fierce assault by aggressive mongoose gang, watch![submenu-img]() Where is the East India Company, which ruled India for 200 years, now?

Where is the East India Company, which ruled India for 200 years, now?![submenu-img]() Russian woman alleges Delhi airport official wrote his phone number on her ticket, video goes viral

Russian woman alleges Delhi airport official wrote his phone number on her ticket, video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: School teachers build artificial pool in classroom for students, internet loves it

Viral video: School teachers build artificial pool in classroom for students, internet loves it![submenu-img]() Viral video: Wife and 11-year-old son of Bengaluru businessman become Jain monks, details inside

Viral video: Wife and 11-year-old son of Bengaluru businessman become Jain monks, details inside

)

)

)

)

)

)