Within days of the start of the uprising in Egypt, political pundits in Washington began to ask why America’s massive intelligence apparatus had not been able to predict it.

Within days of the start of the uprising in Egypt, political pundits in Washington began to ask why America’s massive intelligence apparatus had not been able to predict it.

Their criticism has the empty benefit of hindsight. History has a habit of blindsiding human beings. It did so in St Petersburg in 1917; in Berlin in 1931, in Moscow in 1992. It tends to do so because although the causes of political change can be identified in advance, the change itself is almost always sudden. Anger that has simmered for years, even decades, suddenly bursts forth and spreads like wild fire. Then there is no stopping it.

Strategic analysts have ascribed the near simultaneous explosions of street power in Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan and Yemen to rising income inequalities, a sharp rise in the cost of food and widespread unemployment. But a closer look shows that their single uniting factor is a revolt against governments that have become increasingly unrepresentative with the passage of time.

All the prote-sts and uprisings are taking place against regimes that are firmly aligned with the US and are therefore, tacitly or explicitly, willing to coexist with Israel. Israel’s relentless nibbling at the West Bank throughout the nineties, George Bush’s Iraq war in 2003, Israel’s attack on Lebanon in 2006, and the unending economic blockade of Gaza for the past five years have made it harder and harder for the rulers to justify their policies. This has forced them to rely more and more heavily on repression to stay in power.

But repression cannot be selective: What may have begun as an attempt to suppress Arab radicalism after the assassination of president Anwar Sadaat, and the end of the First Afghan war, has ended by stifling all forms of political dissent. Repression has bred unaccountability and corruption. One needed only to add global recession, food inflation and unemployment to this deadly mix to make the pot boil over.

As I write, Egypt is on the cusp. The government is holding talks with the dissidents; after 45 years the Muslim brotherhood has been allowed to come out of the cold. The chances of an orderly transition to democracy are getting better. Should this happen the credit will belong not only to Egypt’s suddenly empowered civil society but also in good part to president Obama. He understood within hours that siding with repression now would buy short term stability at the cost of long term chaos. He has therefore urged Mubarak to leave the seemingly safe harbour of authoritarian rule, for the heaving seas of democracy.

The change that is taking place in Egypt and has already taken place in Tunisia is reverberating around the world. King Abdullah of Jordan has changed his prime minister; president Saleh in Yemen has called a joint meeting with all parties to craft a reconciliation.

If this upsurge of democratic sentiment continues, the political map of the Arab world will be changed forever. Israel will be the first to feel its effect, for it will have to look for fresh ways to settle the Palestine issue. But Islamist extremism will be the second loser, for it too has fed upon the intransigence of authoritarian regimes and their willingness to tolerate Israel’s incessant resort to force.

But India will not escape the reverberations either. For it too must answer the question that Tahrir square has posed: what can even the most heavily armed state do when its own people repudiate it? This question needs an urgent answer in Kashmir valley, which has been in a virtual lockdown since June. What will Delhi do if lakhs of Kashmiris converge on Lal Chowk and refuse to leave it till the Abdullah government resigns, the anti-terrorist laws are repealed and the army sent back to the barracks? Will it fire on them? Will it deploy water cannon and rubber bullets as the Egyptian police have done but the JK police and the CRPF have not? Will it declare curfews, and try to prevent demonstrators from getting to Lal Chowk? Or will it forestall having to choose between these grim alternatives by giving democracy one more chance in Kashmir.

It is true that the Omar Abdullah government is an elected government. But as more than one opinion poll in the valley has shown, it is also a government that has lost the support of most of the people in the valley. Is it asking too much of a nation that prides itself on its democracy, to give democracy a chance to sort out the mess in Kashmir? As we are seeing in Egypt, the very least this will do is to empower the moderates and weaken the extremists clustered around Geelani and Masrat Alam. All that Delhi has to do is make up its mind. What it can no longer afford is to do nothing. Today it is like a deer caught in the headlights of a speeding train. It has to jump off the tracks , and is rapidly running out of time.

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

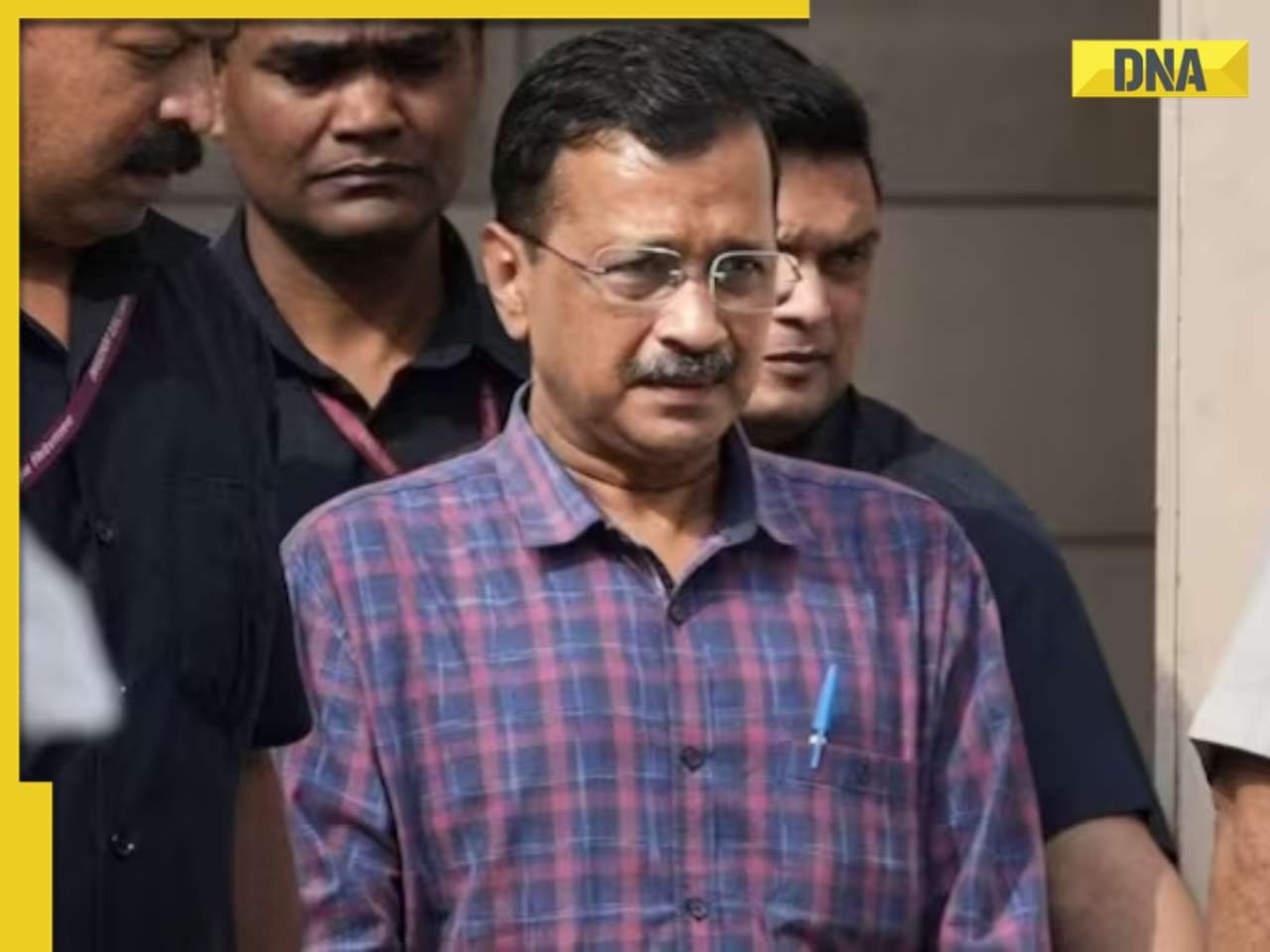

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

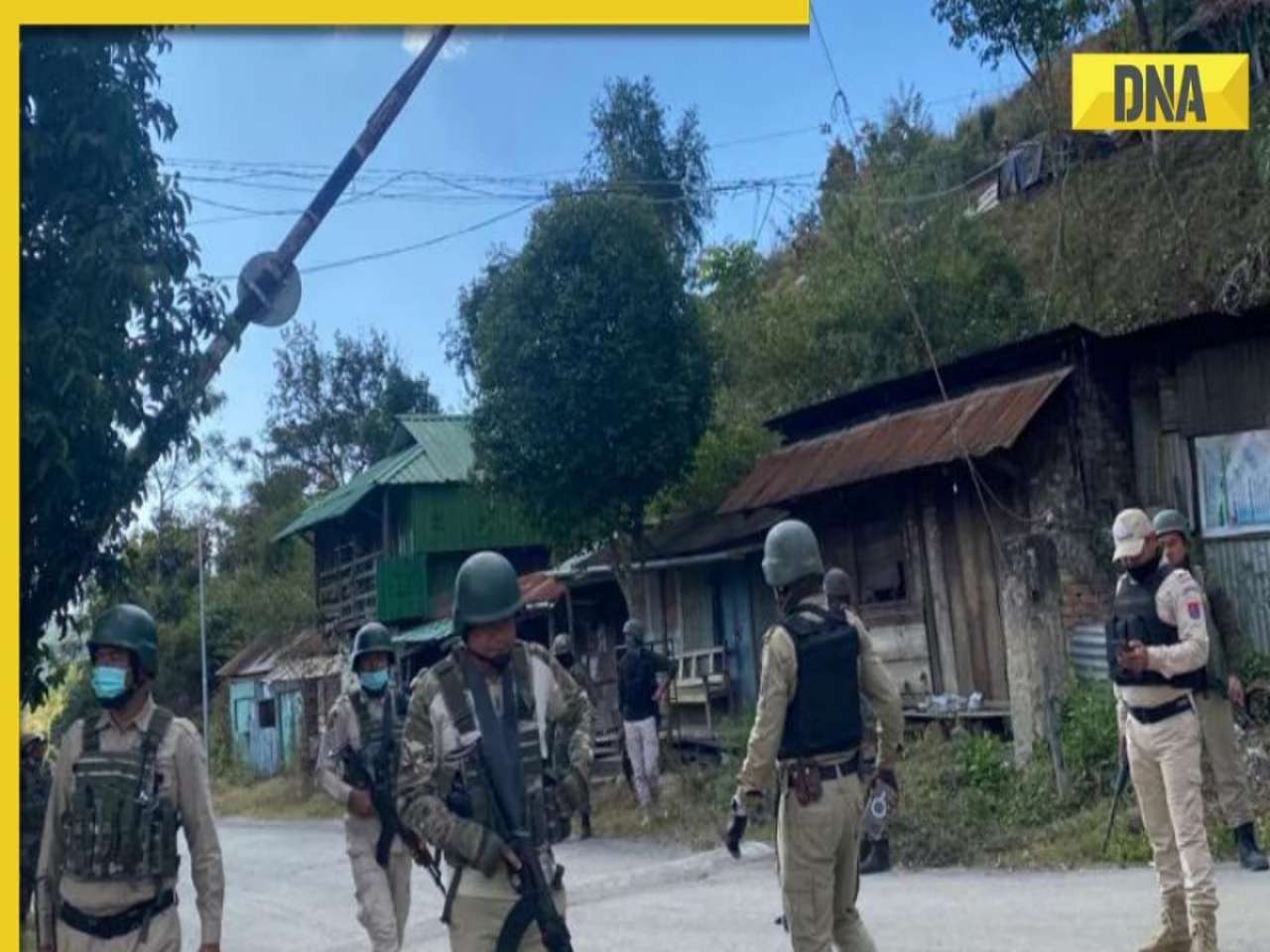

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

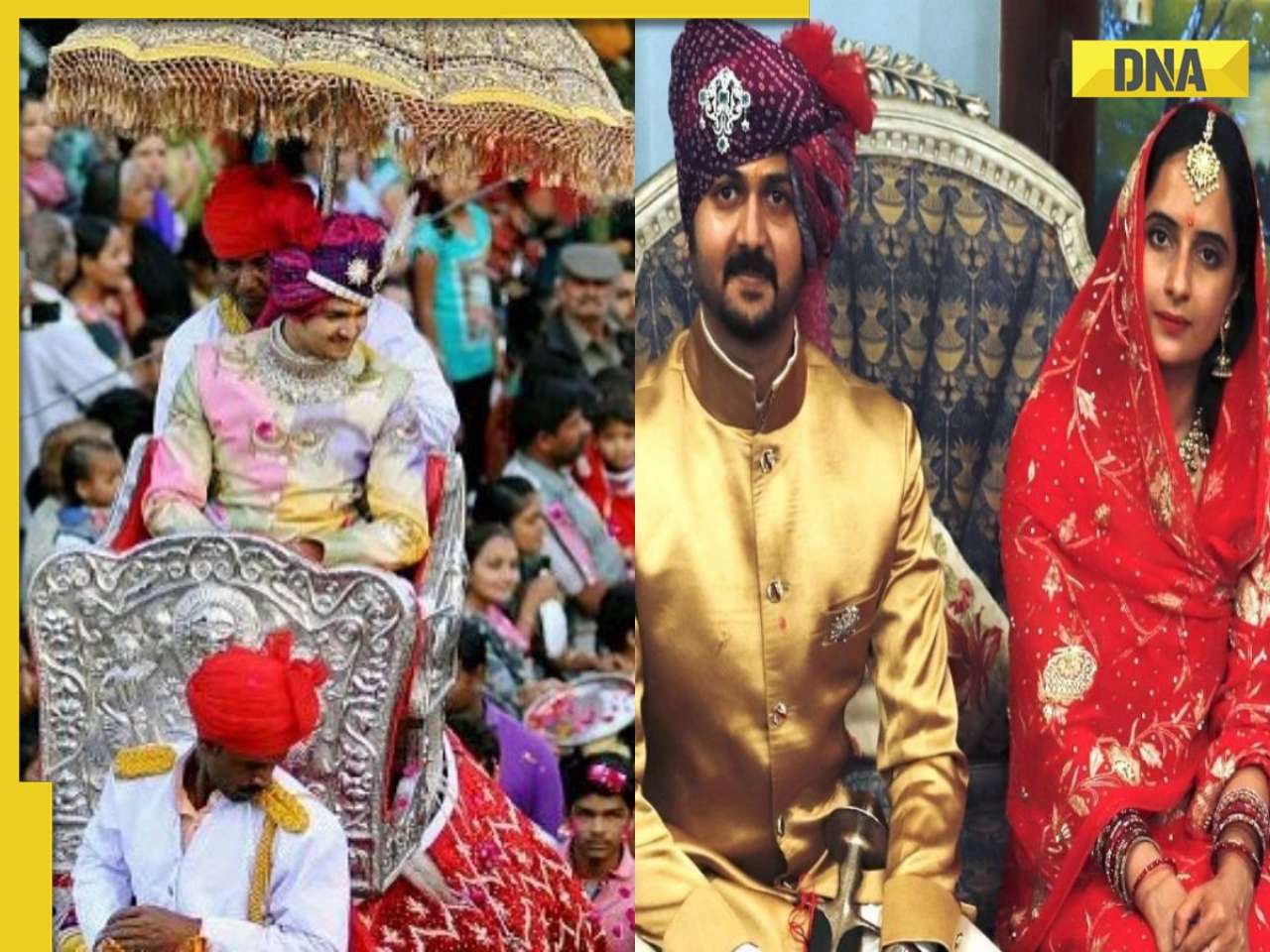

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)