When the earthquake struck, at 2.46pm on March 11, 2011, Sasaki Hideharu knew exactly what to do. But things took a turn for the worse...

When the earthquake struck, at 2.46pm on March 11, 2011, Sasaki Hideharu knew exactly what to do.

The reserved but capable 39-year-old waited for the ground to stop shaking, and the glass to stop falling, and then dashed up the wide staircase outside his workplace, the sports centre in the sleepy town of Rikuzentakata. The cream, two-storey, octagonal building had been designated as one of the town's tsunami evacuation centres and Sasaki knew that a wave was on its way, and that people would soon start filing in from the houses nearby.

"I was looking for a radio, so I could find out how big the tsunami would be," he said. "When I found one, the reports said Miyagi would be struck by a six-metre (20ft) wave, so I thought it would be the same here."

Actually the tsunami was 46ft high when it washed into Rikuzentakata, up to the roof of the sports centre.

That mistake cost the lives of everyone he helped to usher into the building, between 80 and 100 people, he estimates. He has lived for the past year with the knowledge that, despite following procedure, he was unable to save his friends and colleagues. Only four people, including him, managed to survive.

On Sunday, as Rikuzentakata gathers to remember the disaster, he will not be attending. "I want to visit the families of my friends who died. But I am not sure if that would be the right thing to do."

Standing outside the wrecked sports centre, he said the fear "never entered" his mind that it would not be a safe place to shelter.

Today the centre is a desolate sight, one of the few buildings in a plain where houses once stood. Its face has been ripped off, leaving girders and wires dangling.

Inside, there is sand on every surface. The back wall was punched through by the force of the tsunami and there is still an upturned car in the middle of the wooden floor.

"As the people made their way here, I told them all to go up the outside staircase to the second floor. We had about half an hour from the earthquake to get everyone up. I was at the top of the staircase helping the disabled, people in wheelchairs, the older people," he said.

Then he looked up at the sea. Rikuzentakata sits in a bay about two miles wide, its flat plain surrounded by a horseshoe of hills. The town farms oysters in the shallow waters. The sports centre is about a third of a mile from the sea.

"First I saw the water coming through a line of pine trees near the bay. Then I saw it reach the houses. Then I saw the houses moving towards us," he said. "It was not an angry wave, it looked quite unthreatening. It just slowly crept up. And then suddenly it was there, an enormous mass of water. When I saw the houses being swept towards us, I realised suddenly we might not be safe. Then people started to panic and to run away from the water, towards the back of the hall where there are lavatories. But I knew we would be trapped. I knew this was not the place we needed to be."

It took just one minute for the water to rise from the floor of the sports centre to the second-floor gallery. By the time that Sasaki realised the evacuees had made a mistake, the water was up to his knees.

"I reached the lavatories at the back and turned around. I saw the huge plate glass window at the front of the hall shatter and a wave of water rush in," he said. Then, in a split second, his head was under water. "I gasped, and inhaled a mouthful of seawater. I started to choke, to panic, and immediately I thought this was the end. But then, as images of my three children flashed before me, I became determined I would not die that day."

He bit down on his sleeve to stop himself from breathing in any more water, and scrabbled to get a grip. Finally, as his body rose, he managed to hold on to a pipe.

"I could feel other hands brushing my body. There were people all around. I grabbed one hand and tugged hard, trying to bring it up with me, but it slipped out of my grip."

As the water rose, he was able to find an air pocket at the top and craned his neck to take two breaths. For the next 10 minutes, he rose and fell, searching for mouthfuls of oxygen. Finally the water began to fall, little by little.

After he finally fell to the floor, he went in the semidarkness to search for a child's voice he had heard crying out. It turned out to be a woman, Yoshida Chikako, who had been shouting out for her husband as he slipped away from her. Together with a third survivor, they waited out the first night, shivering in wet clothes, in the winter cold, in the twisted wreckage.

"In the other bathroom, there were about 10 bodies. In the hall, people had got caught in the beams, and their bodies hung down limply. As I looked at the wave retreating, I will never forget the sound of all the wood floors snapping, cracking and warping."

Sasaki said he had tried to exorcise his demons by throwing himself into emergency work, delivering aid to the people left homeless, and by seeking out and visiting some 20 families of victims who died in the sports centre.

"We had enough time to escape, to get to higher ground," he said. "If the radio had said the wave would be 10 metres, instead of six, I am sure that someone would have suggested we move everyone elsewhere. Maybe I would have suggested it."

![submenu-img]() Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'

Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'![submenu-img]() Weather updates: IMD issues severe heatwave condition in these states; check forecast here

Weather updates: IMD issues severe heatwave condition in these states; check forecast here![submenu-img]() Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case

Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case![submenu-img]() Bank Holidays in May 2024: Branches to remain closed for 10 days this month, check full list

Bank Holidays in May 2024: Branches to remain closed for 10 days this month, check full list![submenu-img]() Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'

Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'

Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'![submenu-img]() Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case

Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case![submenu-img]() Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'

Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan recalls ex-wife Reena Dutta slapping him when she was in labour: 'She even bit my hand'

Aamir Khan recalls ex-wife Reena Dutta slapping him when she was in labour: 'She even bit my hand'![submenu-img]() Britney Spears settles legal dispute with estranged father Jamie Spears over conservatorship, details inside

Britney Spears settles legal dispute with estranged father Jamie Spears over conservatorship, details inside![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Sanju Samson, Dhruv Jurel fifties help Rajasthan Royals take down LSG by 7 wickets in Lucknow

IPL 2024: Sanju Samson, Dhruv Jurel fifties help Rajasthan Royals take down LSG by 7 wickets in Lucknow![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Mumbai Indians by 10 runs

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Mumbai Indians by 10 runs![submenu-img]() CSK vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Rasikh Dar power DC to 10-run win over MI

IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Rasikh Dar power DC to 10-run win over MI![submenu-img]() 'If I don’t get a chance despite...': Shubman Gill makes big statement ahead of T20 World Cup 2024

'If I don’t get a chance despite...': Shubman Gill makes big statement ahead of T20 World Cup 2024![submenu-img]() Viral video: Rediscover childhood bliss with this nostalgic 90s birthday party plate, watch

Viral video: Rediscover childhood bliss with this nostalgic 90s birthday party plate, watch![submenu-img]() Ever seen elephant playing cricket? This viral video will leave you stunned

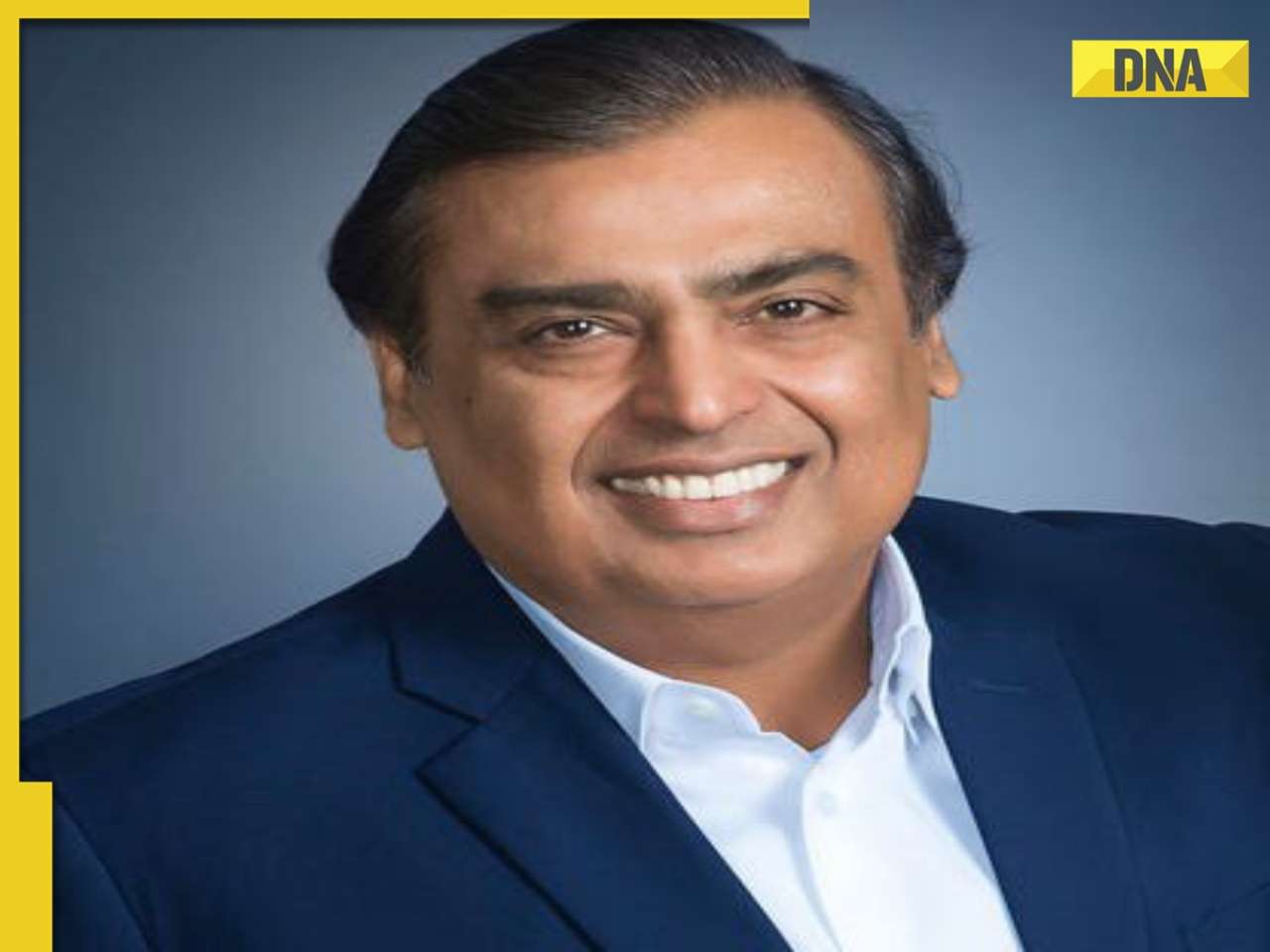

Ever seen elephant playing cricket? This viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani lost 15 kgs without any workout, his secret diet plan includes...

Mukesh Ambani lost 15 kgs without any workout, his secret diet plan includes...![submenu-img]() Viral video: Groom's daring leap during varmala ceremony leaves internet in stitches, watch

Viral video: Groom's daring leap during varmala ceremony leaves internet in stitches, watch![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)