Bo was already controversial for thrusting forward "red" Chongqing as a bold alternative model for China.

Bo Xilai received a hint of a gathering storm that would soon topple him and shake China's ruling Communist Party in the form of an oblique warning about the weather. Bo had flown to Beijing from Chongqing, his city power-base in the southwest, for the annual session of the party-run parliament.

He was struggling to subdue an uproar after his police chief took refuge in a US consulate for a day. Telegenic and self-assured in a political elite crowded with wary conformists, Bo was already controversial for thrusting forward "red" Chongqing as a bold alternative model for China.

The astounding antics of his long-time aide, Vice-Mayor Wang Lijun, threatened to spoil parliament's show of unity and Bo's run for a place in the party's innermost circle of power.

The warning came on March 3 from a senior central leader who told Bo and other assembled officials in Chongqing to be careful while attending the parliament session in Beijing.

"The climate in Chongqing is very different from the climate in Beijing," said the official, who several sources have told Reuters was He Guoqiang, the Party's top man for keeping discipline and fighting corruption.

Beijing's political winds indeed turned brutally against Bo.

His removal as party chief of Chongqing was announced last week, stoking uncertainty about how China will manage a tricky handover later this year to a new generation of leaders at the 18th Communist Party Congress.

A reconstruction of the events leading to Wang's flight and Bo's downfall offers insight on how China is run that reaches far beyond their political base in Chongqing, a smoggy city-province of 30 million people on the Yangtze River.

Wang's flight to the US consulate in nearby Chengdu was not the "isolated incident" Chinese officials first described.

In interviews in Beijing and Chongqing, serving officials, retired cadres, Chinese journalists and other sources close to the government called it a climactic outburst of tensions that stretched back a year and involved the top reaches of China's leadership.

The tale involves allegations of corruption and abuse of power by Bo's family, bugging of senior leaders, and growing distrust between Bo and Wang. Above all, Bo's rise and abrupt fall as a hero of leftist supporters exposed ideological rifts that threaten to tear at party unity if the leadership mishandles his departure.

"The loss of Bo Xilai means the whole balance of the 18th Congress succession preparations has been disturbed," said Li Weidong, an editor and commentator in Beijing who has closely followed the unfolding scandal.

"Finding the right equilibrium will be more difficult." Since China's secretive political system discourages people from speaking candidly about contentious news, most of the people interviewed for this report demanded anonymity.

Wang's flight to the US consulate in Chengdu on Feb. 6 was not confirmed until later by the Chinese and US governments.

But the intense security surrounding the consulate prompted an outpouring of Internet speculation that made it impossible for party leaders to hush up the scandal.

"It's like politics in an emperor's court. The politics behind the screen is very secretive until a crisis exposes all the players," said Li, the Beijing commentator. Just days earlier, Bo had removed Wang as public security chief and appointed him vice-mayor for education, science and culture.

It was an abrupt demotion for a career police officer whose campaign against crime overlords in Chongqing had won him and Bo flattering national attention in 2009. Distrust had been mounting between the two, according to a former official who said he has often met Bo and his family.

"Relations between Bo and Wang began to really sour in January, but it was a process deepening over months." Bo "forced Wang Lijun out of his police uniform, which made him fall into even deeper despair and panic about his future. At the very least, it looked dictatorial and arbitrary. It made a bad relationship much worse," the former official said. Days before the demotion, Wang had confronted Bo over a criminal investigation touching on Bo's family, including his wife Gu Kailai, and that a task force had been assembled to handle the case, two former officials said. "It was because of this special case group that relations finally snapped," said the first retired official.

Talk spread among Chongqing officials of furious shouting between Bo and Wang, and even of Bo slapping his long-time ally, a city official said.

"Bo felt Wang Lijun was using this (case) to take him hostage," said an editor in Beijing who said he heard about the episode from central government officials.

"Bo was furious and then he decided to adjust Wang's position to protect himself."

Self-protection and self-promotion came easily to Bo. His upbringing as the "princeling", son of revolutionary leader Bo Yibo, dubbed one of the "Eight Immortals", had imbued him with ambition, confidence and a sometimes dismissive impatience with subordinates and even superiors, said several people who had dealings with him.

"The red second generation feel that they naturally deserve to be on top, and the current leaders have been too weak," said a former Chongqing official turned businessman. After arriving in Chongqing in 2007, Bo turned it into a bastion of Communist "red" culture and egalitarian growth, winning national attention with the crackdown on organised crime that jailed or even executed officials accused of protecting crime bosses. It was a bold comeback for a sharp-suited and sharp-elbowed politician whose assignment to Chongqing was widely seen as a grimy exile after serving as commerce minister since 2003. The campaign against endemic corruption could not have cast either of his predecessors there in a good light: Wang Yang, now governor of Guangdong and a candidate for a coveted position on the Standing Committee; and He Guoqiang, the disciplinarian. Bo's populist social and economic reform, and crime clean-up won a large following who hoped he could try his policies nationwide as a member of the Communist Party's next generation of central leaders who will emerge in late 2012.

His bald self-promotion and Maoist revivals, however, irked pro-market liberals, as did his courting of left-wing intellectuals who lauded the "Chongqing model". "Bo made a big gamble in Chongqing. He played a card that he could set the direction for the whole country," said Zhu Zhiyong, a former businessman in Chongqing who has been critical of Bo. "It breaks the rules of politics."

Contention over whether Bo would win a place in the Party's next Standing Committee, the inner core of power now with nine members, intensified last year, and added to the tensions that turned Bo and Wang against each other, said several sources close to Chongqing leaders.

"A group in the central leadership has been adamantly opposed to Bo's entry, because he was seen as a trouble-maker who doesn't respect the rules," said the former official, who has often met Bo and other senior leaders. "The most likely possibility is that high-level people didn't want Bo to rise, so they took aim at Wang Lijun." The central leader who played a key role in marshalling accusations against Bo and Wang was He Guoqiang, said the ex-official and several other sources. From 1999 to 2002, He was party chief of Chongqing, watching as his acolytes in government there were sidelined under Bo's campaigns. As head of the party's Central Discipline Inspection Commission, he backed corruption investigations that could damage Bo, said the sources. By last year, He had seen enough, and began driving the initial wedge between Wang and Bo. "He Guoqiang supported investigating Wang Lijun to go after Bo Xilai," said a Chongqing official.

He's gambit, according to this account, worked to perfection. Distrust between the once close allies broke down "and so then Wang Lijun began to turn to blackmail to protect himself", the Chongqing official said

As of late January, Bo was still focused on securing a spot in the Communist Party core leadership. The top job, successor to President Hu Jintao, is almost sure to go to Vice-President Xi Jinping. Bo had been leading the pack of provincial chiefs whose prominence, age and connections made them contenders for spots around Xi. On Jan. 9, the top Party newspaper, the People's Daily, devoted the top of its front-page to effusive praise for Chongqing's successes. Foreign heavyweights, including former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, had flown to Chongqing to meet Bo and admire the steel and glass buildings rising along the steep sides of the Yangtze.

Chongqing claimed to have achieved China's fastest growth rate for any province-level area, 16.4%. Then came Wang's stunning dash to the consulate of China's chief rival. He was worn out and emotionally spent and had taken "vacation-style therapy", the city initially explained.

With the national parliament in session, the central government also tried to play down the incident, with an official scolding the media for speculating about it and praising Chongqing's successes.

"Initially, the central leadership wanted to cool things down during the parliament session, but that failed," said a former Chongqing official. Wang, meanwhile, was in custody, raising the possibility that damaging information about Bo could come out. Two sources said word had spread in government circles that Bo and Wang were suspected of bugging rivals and even central leaders. Bo seized his chance to explain himself at a March 9 news conference at the parliament, and did so in his characteristically brash style. Bo dismissed as "nonsense" reports, circulated on the Chinese internet and backed by diplomats' sightings, that his son, Bo Guagua, whizzed around Beijing in a red Ferrari, and scholarships paid his expensive education at Oxford and Harvard.

"These people who have formed criminal blocs have wide social ties and the ability to shape opinion," Bo said of his critics.

"There are also, for example, people who have poured filth on Chongqing, and poured filth on myself and my family." Central leaders had had enough. They were riled by Bo's decision to brandish contempt for foes, rather than show contrition. They were especially irked by Bo's comment he was confident Hu would visit Chongqing, implicitly claiming the confidence of China's president.

Accounts vary of when the party leadership decided Bo had to go, but most sources said the curtain fell within 72 hours of his combative news conference. At a post-parliament news conference five days after Bo's performance, Premier Wen Jiabao suggested Bo was culpable not only for Wang's flight but also for conjuring up false nostalgia for Mao's era.

China needed political reform, without which "such historical tragedies as the Cultural Revolution may happen again in China", Wen said. "Wen's words revealed the split," said the former Chongqing official.

"It turned this into a line struggle."

The next day, the government announced Bo had been removed as party secretary of Chongqing. China's leaders now appear uncertain about how to deal with the downfall of a popular politician.

"The 18th Congress outcome hasn't been settled yet, and this makes it more difficult, because Bo Xilai represented many left-leaning voices in China," said Wang Wen, a Beijing journalist who has met Bo. A week after his fall, Bo remains out of sight, with unconfirmed speculation he remains in Beijing available for questioning. His abrupt departure has kindled wild rumours, including one this week of a coup attempt.

"The game is not over yet. There's no full-stop on this yet," said the ex-official familiar with Bo.

![submenu-img]() Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'

Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'![submenu-img]() Weather updates: IMD issues severe heatwave condition in these states; check forecast here

Weather updates: IMD issues severe heatwave condition in these states; check forecast here![submenu-img]() Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case

Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case![submenu-img]() Bank Holidays in May 2024: Branches to remain closed for 10 days this month, check full list

Bank Holidays in May 2024: Branches to remain closed for 10 days this month, check full list![submenu-img]() Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'

Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'

Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'![submenu-img]() Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case

Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case![submenu-img]() Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'

Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan recalls ex-wife Reena Dutta slapping him when she was in labour: 'She even bit my hand'

Aamir Khan recalls ex-wife Reena Dutta slapping him when she was in labour: 'She even bit my hand'![submenu-img]() Britney Spears settles legal dispute with estranged father Jamie Spears over conservatorship, details inside

Britney Spears settles legal dispute with estranged father Jamie Spears over conservatorship, details inside![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Sanju Samson, Dhruv Jurel fifties help Rajasthan Royals take down LSG by 7 wickets in Lucknow

IPL 2024: Sanju Samson, Dhruv Jurel fifties help Rajasthan Royals take down LSG by 7 wickets in Lucknow![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Mumbai Indians by 10 runs

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Mumbai Indians by 10 runs![submenu-img]() CSK vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Rasikh Dar power DC to 10-run win over MI

IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Rasikh Dar power DC to 10-run win over MI![submenu-img]() 'If I don’t get a chance despite...': Shubman Gill makes big statement ahead of T20 World Cup 2024

'If I don’t get a chance despite...': Shubman Gill makes big statement ahead of T20 World Cup 2024![submenu-img]() Viral video: Rediscover childhood bliss with this nostalgic 90s birthday party plate, watch

Viral video: Rediscover childhood bliss with this nostalgic 90s birthday party plate, watch![submenu-img]() Ever seen elephant playing cricket? This viral video will leave you stunned

Ever seen elephant playing cricket? This viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani lost 15 kgs without any workout, his secret diet plan includes...

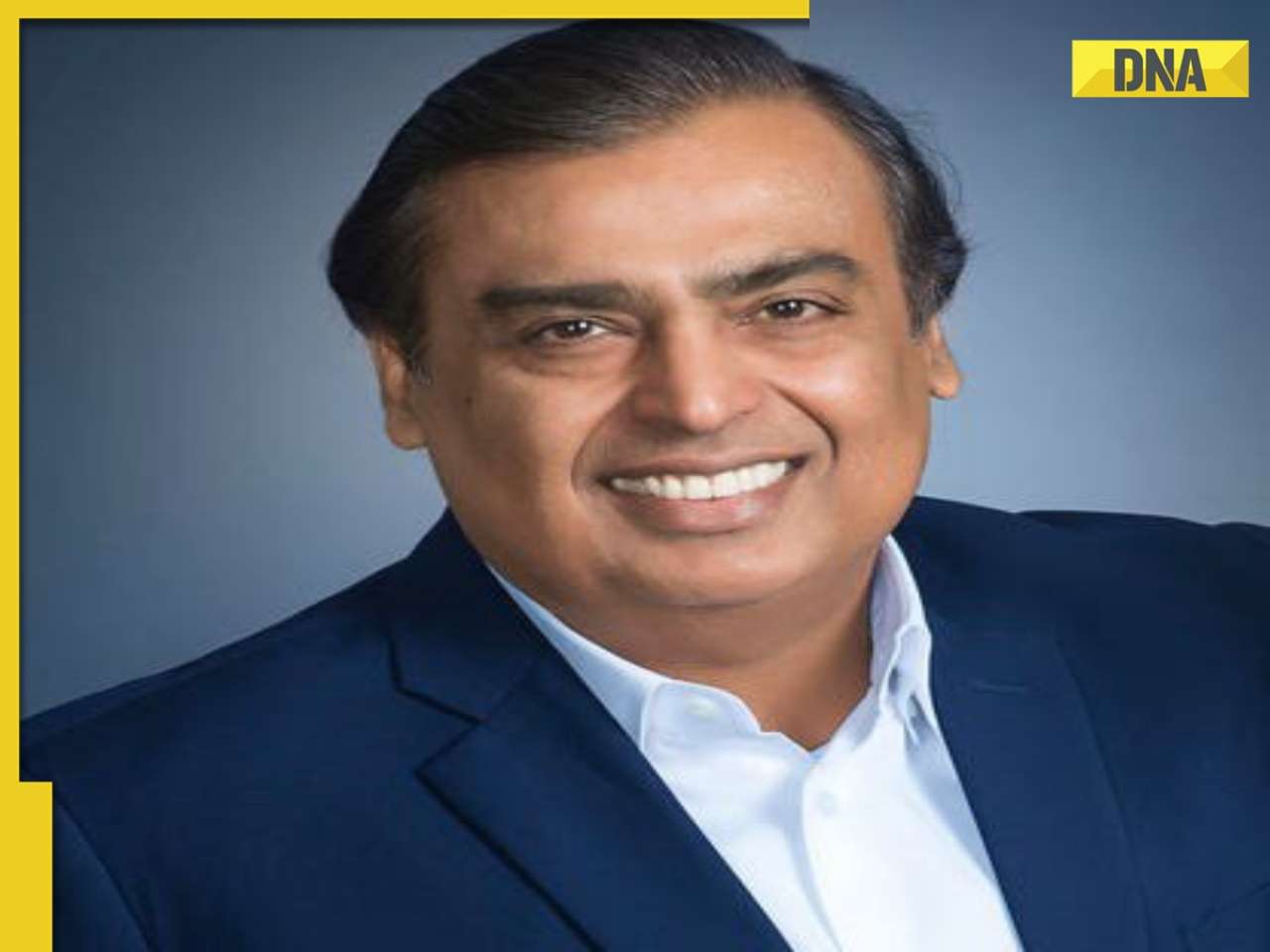

Mukesh Ambani lost 15 kgs without any workout, his secret diet plan includes...![submenu-img]() Viral video: Groom's daring leap during varmala ceremony leaves internet in stitches, watch

Viral video: Groom's daring leap during varmala ceremony leaves internet in stitches, watch![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)