Raja Rao, who turns 97 this week, will always be remembered for his rigorously philosophical novels, writes Makarand Paranjape

I am not sure I’ll see Raja Rao again. Rao, who turns 97 on Tuesday, is not the man he once was.

The last time I met him, in America, he could not remember the names of his own books, among them such acclaimed works as Kanthapura (1938) and The Serpent And The Rope (1960), which brought him international renown years ago.

His short-term memory was almost gone. He thought I was a literary agent who had come to take a look at his unpublished work.

His third wife, Susan, many years younger to him, is an American woman who has tended to him more devotedly than any Indian wife possibly could. She made us some excellent pumpkin soup.

Her kitchen, in Raja Rao’s small apartment on Pearl Street, Austin, Texas, always smelled of herbs. Everything served at her table was organically grown and, of course, vegetarian.

I had, as a matter of fact, come to look at Raja Rao’s unpublished manuscripts. There were dozens of them, with scribbles in Raja Rao’s own hand in the margins. The manuscripts included two volumes of the Chessmaster trilogy.

Only the first volume, The Chessmaster And His Moves, had been published in 1988. It had won Rao the Neustadt Prize, often called the ‘alternative Nobel’. Now I’m not sure if these works will ever be published. Who else but Raja Rao can approve and oversee their final versions?

Raja Rao has always been small and frail. Yet, there is nothing small or frail about his life. If his story were to be told in celluloid, it would be a 70mm film, with an international star cast. It would show a handsome young Brahmin arriving in Paris in the late 1920s, marrying a French professor much older than him, giving up his PhD to pursue a writing career.

Later, the marriage would break up and Raja Rao would return to India to look for a guru. After a decisive event in which, as he put it, he prostrated before Ramana Maharshi in Tiruvannamalai in Tamil Nadu, weeping till the floor was bathed in his tears, Raja Rao finally turned further southwards, to the ashram of Atmananda Guru in Kerala.

Raja Rao wrote The Cat And Shakespeare (1965) based on his ashram experiences and returned to America. He taught philosophy at the University of Texas. His classes were very popular. He was known to walk into the lecture theatre filled with 250 young, inquisitive minds and say, “You may ask me any question you like.”

After an unsuccessful marriage with Catherine Jones, a dancer and an actress, from which a son, Christopher Rama, was born, Raja Rao met Susan, once again in his guru’s ashram.

Living in semi-retirement in his modest apartment in Austin, Raja Rao continued to write. One of his last published books was The Meaning of India (1998).

What makes Raja Rao’s fiction unique is not just the highly innovative, experimental, and dynamic English prose style that he developed much before Salman Rushdie, but the deeply spiritual content of his works. His spirituality is not of a New Age feel good kind, but philosophically rigorous.

He is a novelist of ideas, but the idea is always suggestive of something beyond itself, pointing, ultimately, to the Absolute.

Kanthapura was a lyrical tale that depicted the impact of Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent revolution on a small village in Karnataka.

From there Raja Rao shifted to the Upanishadic, even Sanskritic style and tone of The Serpent And The Rope. The title refers to the advaita analogy of how, because of delusion, the rope appears as the serpent. The book is about the quest for self-knowledge, but weaved into it is a love story, modelled on Raja Rao’s own life.

The metaphysical terrain of The Serpent… is reiterated more elaborately in The Chessmaster And His Moves. This voluminous work ponders on the universal sorrow and the human condition. The solution is not so much the realisation of the self, but its dissolution, the sheer vertical plunge into the Absolute rather than the painstaking, slow, accumulative, and maybe impossible quest for infinity.

Raja Rao considered his writing a sadhana, a spiritual discipline. Reading him is also a sadhana. Like the great Russian writers Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, his fiction elevates the spirit, taking the reader to a higher plane of consciousness.

‘The word seems to come first as an impulsion from the nowhere...’

I am a man of silence. And words emerge from that silence with light, of light, and light is sacred. One wonders that there is the world at all—Sabda—and one asks oneself, where did it come from? How does it arise? I have asked this question for many, many years. I’ve asked it of linguists, I’ve asked it of poets, I’ve asked it of scholars.

The word seems to come first as an impulsion from the nowhere, and then as a prehension, and it becomes less and less esoteric — till it begins to be concrete. And the concrete becoming ever more earthy, and the earthy communicated, as the common word, alas seems to possess least of that original light.

From Raja Rao’s Neustadt Prize acceptance speech.

The writer has edited The Best of Raja Rao (Katha)

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

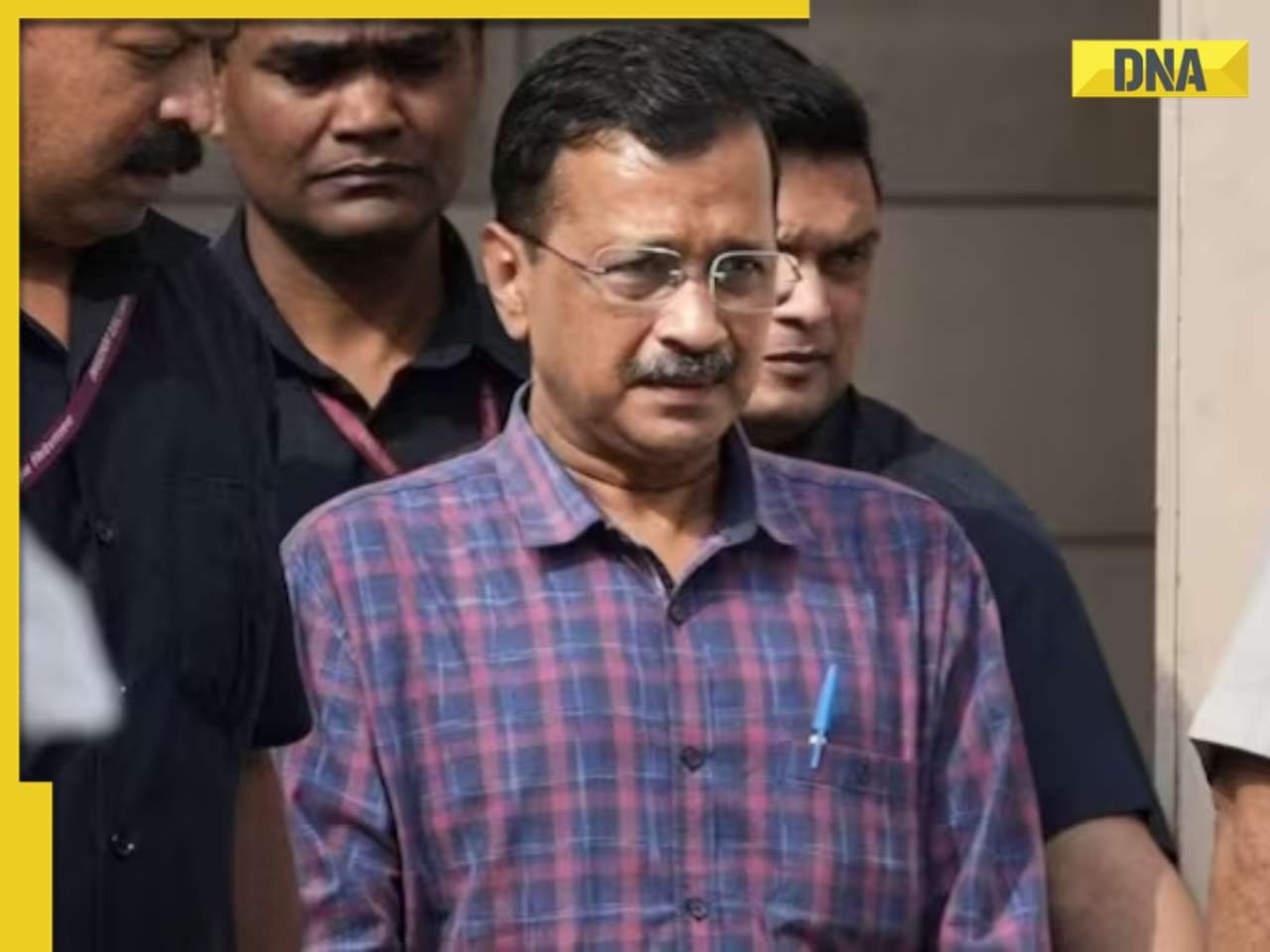

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

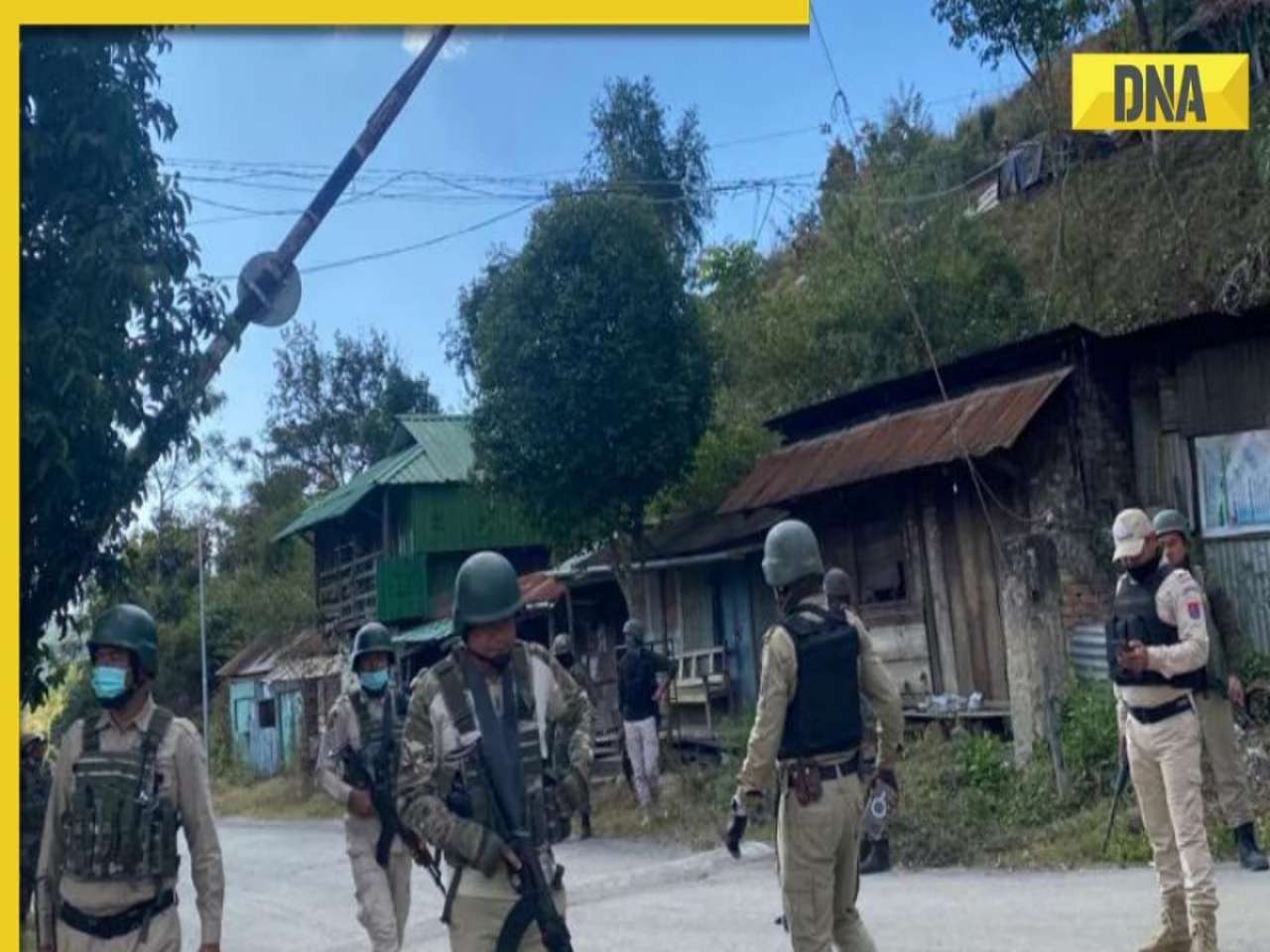

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)