Sectors such as manufacturing, infrastructure and real estate show symptoms of asphyxiation by Fx.

Sumit Sapra is a member of that ambitious, impatient generation of young Indians who rode the crest of the global economy. In five years, he changed jobs three times, quadrupling his salary along the way.

Even when satisfied with his position, he kept his resume posted on job sites, in case better offers came along. And he splurged. In three years, he bought three cars, moving up a notch in luxury each time. For weekend jaunts, he bought a motorcycle.

Sapra’s last and best-paying job was at the Indian headquarters of the financial services arm of General Electric, investing western money in Indian energy projects. But last December, foreign money dried up and Sapra, with a prestigious degree, was laid off.

“Earlier it was money chasing a few projects,” Sapra, 30, said of the change that seemed to come virtually overnight. “Now it’s the other way around.”

Not long ago, Indian leaders confidently predicted this country would emerge largely unscathed from the global economic crisis. It is now becoming clear that that view was too optimistic, nowhere more so than in this city south of New Delhi that

was once the symbol of India’s economic boom.

A few short years ago, construction sites here buzzed 24 hours a day, crews working through the night, cramming down food from onsite trucks during breaks in the twilight. Now real estate sites lie fallow. The once-booming art market has slowed to a crawl. And charmed professionals with coveted degrees, like Sumit Sapra, are unemployed or taking pay cuts to hold on to their jobs.

India’s phenomenal growth of the last five years was powered in large part by huge injections of cash and investment. Investment accounted for about 39% of the country’s gross domestic product in the 2008 fiscal, up from 25% five years ago. At its peak, more than a third of investment came from abroad, according to Credit Suisse.

But in the last three months of last year, foreign loans and direct investment fell by nearly a third, to their lowest level in more than two years.

In a recent report, the International Monetary Fund said Indian companies were among the world’s most vulnerable, after American firms, because they borrowed aggressively during the boom. Using data from Moody’s, the credit rating firm, the IMF estimated in a recent report that defaults among non-financial South Asian firms could climb to 20% in the coming year, up from an expectation of 4.2% a year earlier. American firms, in comparison, are expected to default on loans at a rate of 23%.

The decline in foreign investment has taken a big toll on sectors like real estate, manufacturing, infrastructure and even art, which was bolstered by demand from globalisation’s nouveau riche here and abroad.

In the last quarter of 2008, the economy’s growth rate plummeted to about 5.3%, the lowest in five years. While consumer demand, particularly in the countryside, has kept the economy growing, the sudden slowing in the flow of foreign funds will make it harder for the country to grow fast enough to pull hundreds of millions of people out of stifling poverty.

“If India wants to go back to the 8-9% growth rate, private investment and low cost of capital is essential,” said Jahangir Aziz, the chief economist for India at JPMorgan Chase.

Indian policymakers say they believe the country will grow at 6% in the coming year, but the IMF forecasts growth of 4.5%.

To help fill the gap left by foreign investment, the government is spending more on infrastructure and social programs. The Reserve Bank of India, India’s central bank, has slashed its benchmark interest rates, but the cost of private loans has not fallen by as much.

After a wrenching 58% drop in the Indian stock market last year, the market is up 42% since its March low and some foreign money has started to flow into equities. But economists like Aziz say the government needs to do a lot more, though few expect bigger interventions until the current elections end and a new government takes power in late May or early June.

![submenu-img]() Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'

Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'![submenu-img]() Weather updates: IMD issues severe heatwave condition in these states; check forecast here

Weather updates: IMD issues severe heatwave condition in these states; check forecast here![submenu-img]() Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case

Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case![submenu-img]() Bank Holidays in May 2024: Branches to remain closed for 10 days this month, check full list

Bank Holidays in May 2024: Branches to remain closed for 10 days this month, check full list![submenu-img]() Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'

Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'

Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'![submenu-img]() Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case

Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case![submenu-img]() Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'

Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan recalls ex-wife Reena Dutta slapping him when she was in labour: 'She even bit my hand'

Aamir Khan recalls ex-wife Reena Dutta slapping him when she was in labour: 'She even bit my hand'![submenu-img]() Britney Spears settles legal dispute with estranged father Jamie Spears over conservatorship, details inside

Britney Spears settles legal dispute with estranged father Jamie Spears over conservatorship, details inside![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Sanju Samson, Dhruv Jurel fifties help Rajasthan Royals take down LSG by 7 wickets in Lucknow

IPL 2024: Sanju Samson, Dhruv Jurel fifties help Rajasthan Royals take down LSG by 7 wickets in Lucknow![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Mumbai Indians by 10 runs

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Mumbai Indians by 10 runs![submenu-img]() CSK vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Rasikh Dar power DC to 10-run win over MI

IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Rasikh Dar power DC to 10-run win over MI![submenu-img]() 'If I don’t get a chance despite...': Shubman Gill makes big statement ahead of T20 World Cup 2024

'If I don’t get a chance despite...': Shubman Gill makes big statement ahead of T20 World Cup 2024![submenu-img]() Viral video: Rediscover childhood bliss with this nostalgic 90s birthday party plate, watch

Viral video: Rediscover childhood bliss with this nostalgic 90s birthday party plate, watch![submenu-img]() Ever seen elephant playing cricket? This viral video will leave you stunned

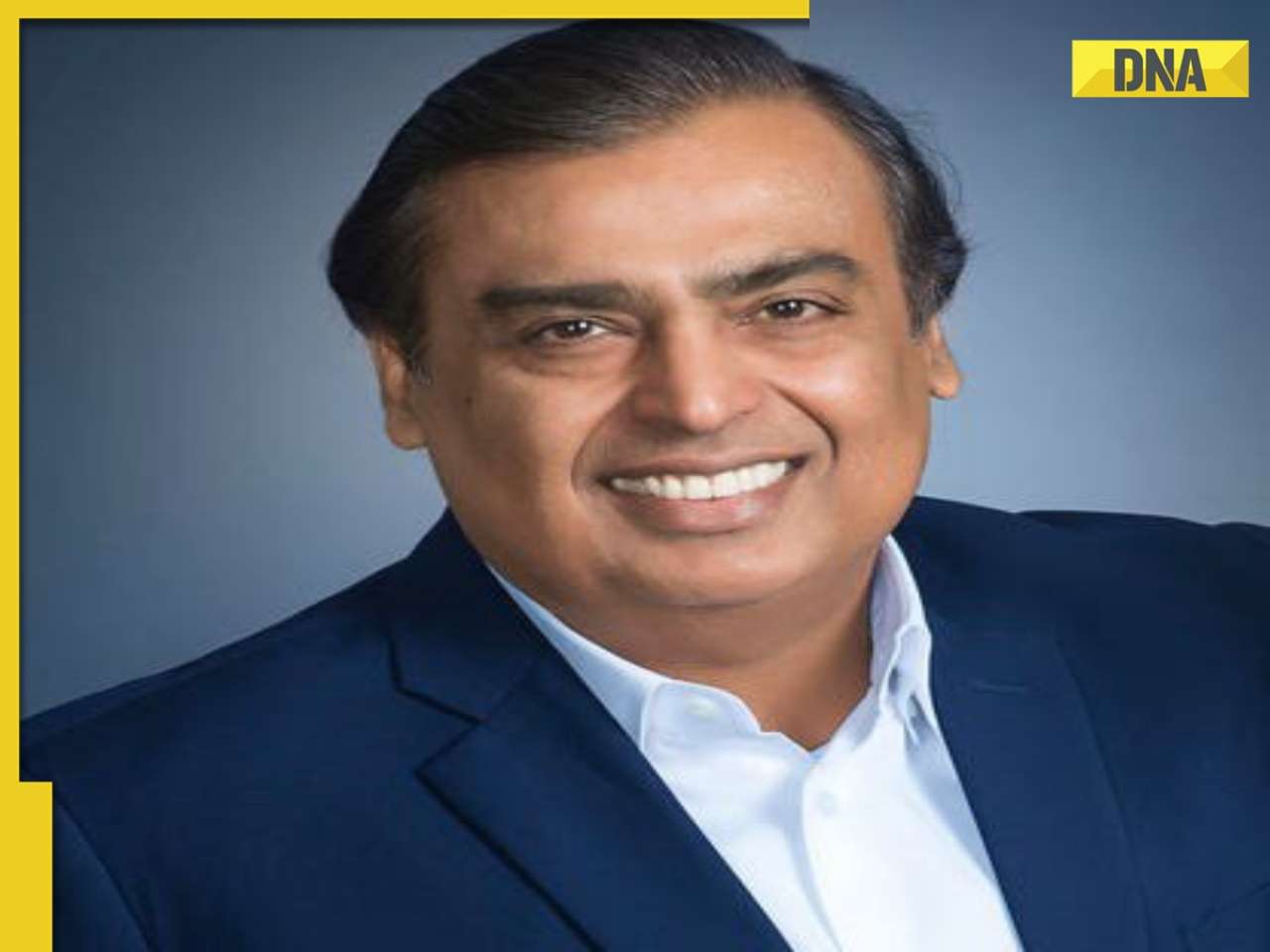

Ever seen elephant playing cricket? This viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani lost 15 kgs without any workout, his secret diet plan includes...

Mukesh Ambani lost 15 kgs without any workout, his secret diet plan includes...![submenu-img]() Viral video: Groom's daring leap during varmala ceremony leaves internet in stitches, watch

Viral video: Groom's daring leap during varmala ceremony leaves internet in stitches, watch![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)