It’s curious the kind of love and hate that

Slumdog inspired in India when it was first released. So many articles, blogs, comments… It spoke to the conscience of the multiplex elite, particularly sensitised after the horrors of late November. But it seemed to annoy those who may have felt that ‘our’ misery was being cashed in on by the west. Or that the chest-thumping Arcelor-buying India was having its dirty laundry washed in front of the world.

Now that ‘we’ have won all these Oscars, the enthusiasm may wash away all traces of the initial indifference the audience showed. Despite the hype,

Slumdog (

millionaire and

crorepati combined) earned approximately 9 crore rupees in the first week of its release; and although 60 per cent of the 350 prints released were in Hindi, only 30 per cent of the collections came from the Hindi version. For some reason, Indian audiences, particularly the Hindi audiences, were not swept away by the film.

There is a small independent film releasing this week that serves as an interesting counterpoint to

Slumdog and may address this question of what

Slumdog missed. Set in Dharavi,

Barah Aana is also about faceless India: a driver, a watchman and a waiter. The people who surround us but whom we may not recognise if we saw them on the street. They are all migrants, fatigued to the bone, but with dreams in their eyes. Not far from

Slumdog, in that they dream big.

But that’s where the parallel ends…

Slumdog is an an outsider’s view of Bombay, the slums, and poverty. It fears poverty, and therefore portrays the slum kids’ lives as unmitigated misery. It’s how we, the privileged, see the lives of the them. Aren’t we lucky to be born where we are? It’s true we are. And we should feel guilty and question the injustice built into the system that affords us our comforts. This is what

Slumdog does so effectively: it appeals to our conscience as the script wends its way around various social ills-from domestic violence to communalism to classism-and it simply doesn’t allow us to turn a blind eye.

Yet, for us to leave our seats satisfied,

Slumdog needs to show the protagonist escape forever the grime and squalor that have turned our insides for the first hour or so. When you leave singing

Jai Ho, you can leave far behind you the kids who are still waiting in line to use that vile toilet.

To be fair to the film, it is a story, and it has a right to a happy ending. It shouldn’t be forced to carry the burden of societal problems that persist. Without its happy ending, it may not have reached the millions that it did. And Azharuddin and Rubina wouldn’t have walked the red carpet.

But that happy ending may be exactly why the single screen audiences have not loved the film. Jamal gets to rise above his misfortunes because he is destined to. Just as some of us were destined or lucky enough to be born where we were. So what does that mean for those who aren’t feeling lucky?

While

Slumdog reached millions across the globe,

Barah Aana has had trouble finding distribution; most likely because it doesn’t have the kind of happy ending that allows us to get away from what makes us deeply uncomfortable about our society. Although it is definitely a less miserable film than

Slumdog, it doesn’t force a hokey happy ending to save our protagonist and make us feel good.

Because everyone doesn’t get saved. At least not by getting a crore, and the girl. But it suggests that there is redemption within real life. And happiness without the crore. Unlike

Slumdog,

Barah Aana is an insider’s view. It does not fear poverty as some kind of

awful third world disease. Yes, there is poverty, misery and hardship.

But there are also friendships and laughter, hope and flirtation...

Barah Aana actually enters the homes of our protagonists. And in their

kholis we see the relationships that make India India. The forced intimacy of a shared space that grows into a real friendship, the sentimental outburst that shows real vulnerability and despair, the handing over of one’s savings without so much as a word said…

The happiness it allows is happiness that is possible. It values small gestures between friends, tenderness towards an unrequited love... and the winning of respect by standing up for oneself. The ultimate difference is that it respects the miserable lives that

Slumdog wants to escape. The question is, do we, for some reason, prefer to believe in impossible happy endings instead of seeing joy in the lives we live? Or did a section of Bombay reject

Slumdog because it missed what sustains us: a

bindaas attitude, humour and friendships?

![submenu-img]() Swara Bhasker reacts to Kangana Ranaut slap incident, says actress-politician used Twitter to 'justify violence'

Swara Bhasker reacts to Kangana Ranaut slap incident, says actress-politician used Twitter to 'justify violence'![submenu-img]() Wayanad or Raebareli? Congress Leader Rahul Gandhi likely to decide on Monday

Wayanad or Raebareli? Congress Leader Rahul Gandhi likely to decide on Monday![submenu-img]() PM Modi to flag off 2 new Vande Bharat trains on this date, check route, timetable, and other details

PM Modi to flag off 2 new Vande Bharat trains on this date, check route, timetable, and other details![submenu-img]() Manipur: Major fire breaks out in abandoned building near CM Biren Singh's residence

Manipur: Major fire breaks out in abandoned building near CM Biren Singh's residence![submenu-img]() Fixed deposits: Which bank is offering highest FD interest rates post RBI's new guidelines?

Fixed deposits: Which bank is offering highest FD interest rates post RBI's new guidelines?![submenu-img]() Meet MIT graduate who secured 42nd rank in UPSC, is now suspended due to..

Meet MIT graduate who secured 42nd rank in UPSC, is now suspended due to..![submenu-img]() Railway Recruitment 2024: Sarkari Naukri alert for 1104 posts, check eligibility and selection process

Railway Recruitment 2024: Sarkari Naukri alert for 1104 posts, check eligibility and selection process![submenu-img]() NEET-UG exam row: 'Transparent process will be...,' assures Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan to students, parents

NEET-UG exam row: 'Transparent process will be...,' assures Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan to students, parents![submenu-img]() Meet man, a tailor's son from Latur, who cracked four competitive exams, aims to become...

Meet man, a tailor's son from Latur, who cracked four competitive exams, aims to become...![submenu-img]() Meet woman who was once a sweeper, single mother, cleared civil services exam to become SDM, now arrested due to...

Meet woman who was once a sweeper, single mother, cleared civil services exam to become SDM, now arrested due to...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did Kangana Ranaut party with gangster Abu Salem? Actress reveals who's with her in viral photo

DNA Verified: Did Kangana Ranaut party with gangster Abu Salem? Actress reveals who's with her in viral photo![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: New Delhi Railway Station to be closed for 4 years? Know the truth here

DNA Verified: New Delhi Railway Station to be closed for 4 years? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here

DNA Verified: Did RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat praise Congress during Lok Sabha Elections 2024? Know the truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() In pics: Raghubir Yadav, Chandan Roy celebrate success of Panchayat season 3 with TVF founder Arunabh Kumar, cast, crew

In pics: Raghubir Yadav, Chandan Roy celebrate success of Panchayat season 3 with TVF founder Arunabh Kumar, cast, crew![submenu-img]() How Kalki 2898 AD makers dared to dream pan-India with its unique promotional campaign for Prabhas-starrer

How Kalki 2898 AD makers dared to dream pan-India with its unique promotional campaign for Prabhas-starrer![submenu-img]() In pics: Prabhas' robotic car Bujji from Kalki 2898 AD takes over Mumbai streets, fans call it 'India's Batmobile'

In pics: Prabhas' robotic car Bujji from Kalki 2898 AD takes over Mumbai streets, fans call it 'India's Batmobile'![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Bade Miyan Chote Miyan, Maidaan, Gullak season 4, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Bade Miyan Chote Miyan, Maidaan, Gullak season 4, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() Lok Sabha Elections 2024 Result: From Smriti Irani to Mehbooba Mufti, these politicians are trailing in their seats

Lok Sabha Elections 2024 Result: From Smriti Irani to Mehbooba Mufti, these politicians are trailing in their seats![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Kafala system that is prevalent in gulf countries? Why is it considered extremely brutal?

DNA Explainer: What is Kafala system that is prevalent in gulf countries? Why is it considered extremely brutal? ![submenu-img]() Lok Sabha Elections 2024: What are exit polls? When and how are they conducted?

Lok Sabha Elections 2024: What are exit polls? When and how are they conducted?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi seen as possible successor to Ayatollah Khamenei?

DNA Explainer: Why was Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi seen as possible successor to Ayatollah Khamenei?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?

DNA Explainer: Why did deceased Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi wear black turban?![submenu-img]() Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?

Iran President Ebrahim Raisi's death: Will it impact gold, oil prices and stock markets?![submenu-img]() Swara Bhasker reacts to Kangana Ranaut slap incident, says actress-politician used Twitter to 'justify violence'

Swara Bhasker reacts to Kangana Ranaut slap incident, says actress-politician used Twitter to 'justify violence'![submenu-img]() Shah Rukh Khan took only Re 1 signing amount for this cult film, gave bulk dates to director, later rejected it for..

Shah Rukh Khan took only Re 1 signing amount for this cult film, gave bulk dates to director, later rejected it for..![submenu-img]() Made in Rs 9 crore, this film became blockbuster, was rejected by six actresses, won three National Awards, earned...

Made in Rs 9 crore, this film became blockbuster, was rejected by six actresses, won three National Awards, earned...![submenu-img]() 'Audience ko drama..': Shiv Shakti star Ram Yashvardhan on creative liberties taken in mythological series, films

'Audience ko drama..': Shiv Shakti star Ram Yashvardhan on creative liberties taken in mythological series, films![submenu-img]() Not Parveen Babi, Zeenat, Sharmila, Neetu, only Bollywood actress to attend Amitabh Bachchan-Jaya's wedding was...

Not Parveen Babi, Zeenat, Sharmila, Neetu, only Bollywood actress to attend Amitabh Bachchan-Jaya's wedding was...![submenu-img]() Stolen Titian Renaissance painting found at London bus stop, set to sell for up to..

Stolen Titian Renaissance painting found at London bus stop, set to sell for up to..![submenu-img]() Student fails Physics, Chemistry in class 12th, tops NEET 2024 exam; candidate’s scorecard goes viral

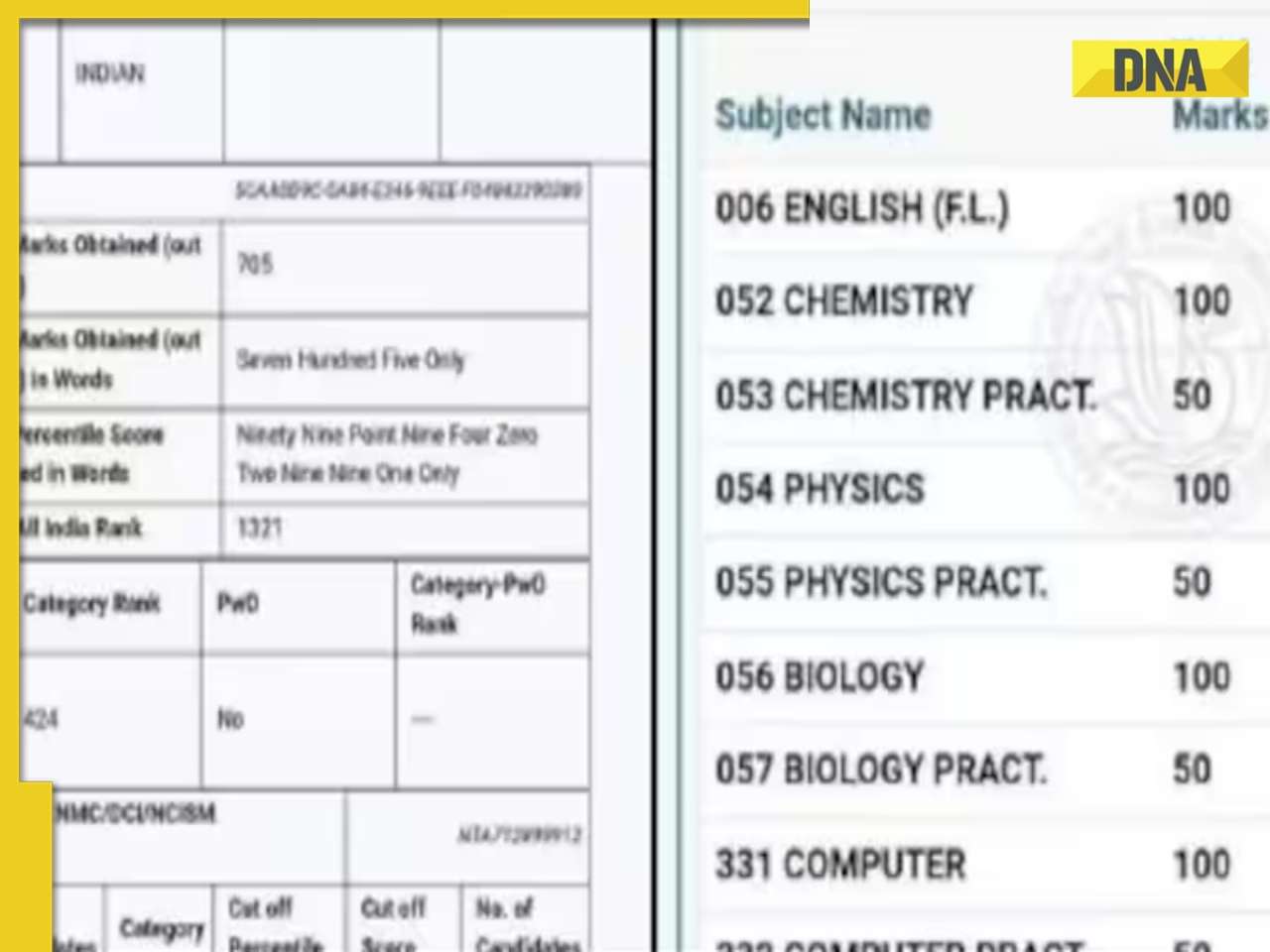

Student fails Physics, Chemistry in class 12th, tops NEET 2024 exam; candidate’s scorecard goes viral![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Italy's PM Giorgia Meloni posts video with PM Modi with 'Melodi' reference

Watch viral video: Italy's PM Giorgia Meloni posts video with PM Modi with 'Melodi' reference![submenu-img]() Girl shocks internet by eating snake like snack in viral video, watch

Girl shocks internet by eating snake like snack in viral video, watch![submenu-img]() Brave or foolhardy? Woman bathes jaguar with pipe, video goes viral

Brave or foolhardy? Woman bathes jaguar with pipe, video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)