A report projects that over the next five years, India will experience a paradox of nearly 90 million persons joining the workforce, but most will lack the requisite skills.

A recent report by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) and the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) titled ‘India’s demographic dilemmas’ analyses the looming skill gaps in the country and the need to urgently address them.

The report projects that over the next five years, India will experience a paradox of nearly 90 million persons joining the workforce, but most will lack the requisite skills and the mindset for productive employment, or for generating incomes through self employment.

The report focuses on four service sectors — ITES, banking, retail and healthcare — and suggests various measures, including changes in human resource policies of the public sector banks, to match skills with future job requirements.

The challenges in addressing the skill gaps are multi-dimensional and require cooperative efforts by all stakeholders. However, the primary responsibility for providing the foundation for manpower development, for India’s emerging knowledge economy, must lie with the government.

Nevertheless, corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, through partnerships between business organisations, the government, particularly at the local level, and not-for-profit sector, can play a vital role in enabling increased access to higher education through both demand-side (e.g. provision of scholarships, general awareness programmes) and supply-side measures (e.g. provision of endowments, making corporate staff available as resource persons, funding research and by contributing to infrastructure).

There is increasing consensus that well-designed CSR initiatives could assist companies domestic and foreign, operating in India, to sustain long-term growth and profitability, while increasing acceptability to local population.

The research suggests that CSR initiatives which are integral to the business and reflect enlightened self-interest are more likely to succeed than those undertaken as charity.

Access to tertiary education remains relatively low in India.

Over 550 million of the country’s population is currently under the age of 25 years, but only 11% of those in the 17-23 age-groups (compared with an average of 23% for the world, 55% for developed countries and 31.5% for Brazil, Russia and China) are enrolled in tertiary institutions, producing about 3 million graduates annually.

Moreover, the Indian graduates, more than 60% of whom are from generic, non-professional disciplines, are unsuitable for knowledge economy work without further training.

The report rightly stresses that while the immediate need is to provide bridging training for those graduating from tertiary institutions, a sustainable strategy must focus on strengthening the educational foundations at the primary and secondary levels, increasing access and de-politicising and de-bureaucratising the higher education sector.

Broader social and economic goals of providing access to education are inconsistent with micro managing, crude social engineering such as reservations and quotas set on arbitrary basis without any sunset clauses, and creating unnecessary hurdles in expanding supply in education sector. The current education policies and mindset must be changed if India is to not only reduce the skills gap but also to provide productive livelihoods to the growing number of young persons entering the labour force.

Several Indian corporations have developed synergistic initiatives towards higher education and vocational training. The illustrative examples include Tata’s Institute of Hotel Management at Aurangabad and ITC Welcomgroup’s Hotel Management Institute, HUL’s Project Shakti and other CSR education initiatives, ITC’s e-Choupal, Reliance’s DA-IICT providing graduate and undergraduate education in Gujarat and Intel’s higher education programme.

Innovations in the design and delivery mechanisms, which could be generated by such CSR initiatives, can help provide a solid empirical base for more effective educational policies, as well as provide feedback from the stakeholders for business innovations.

This will, however, require a change in the mindset of all stakeholders in realising the importance of rigorous evaluation of educational programmes and willingness to alter policies and practices in the light of the findings. Some of the corporations have also been found to be unwilling to subject their CSR initiatives to greater transparency and accountability. This must change.

As the business case for CSR gains ground, companies are increasingly incorporating CSR initiatives in their core business strategies. The companies, which are recognised as front-runners in CSR initiatives, also benefit from easier hiring and retention of top talent, improved productivity, improved market shares and lower cost of funds as fringe benefits of their favourable image.

There is also a significant mismatch between the skills needed to manage India’s increasingly complex, urbanised economy and the civil service recruitment and training policies. This, in turn, is contributing to poor governance. Since the government is a vital stakeholder, its lack of capacity to meet the challenges is undermining India’s economic future. So, CSR initiatives are also needed to address the skill gaps in the public sector. One such initiative could be to develop graduate programmes in public policy to rival those for business administration. The regulatory constraints need to be removed to facilitate this initiative.

The CSR initiatives must also aim at a long-term vision of India as a major knowledge economy. In this connection, there is considerable merit for Indian companies to take leadership in setting up world-class full-fledged universities, combining high quality teaching, research and consultancy activities.

In India, education is under state jurisdiction. Therefore, companies with major presence in a state can work together with the state government to enable such world-class institutions of higher learning to be established.

As India struggles to raise the living standards of the bottom half of its population, such institutions can incorporate vocational training institutes to offer practical, livelihood-earning skills to these people. This can supply a ready pool of skilled labour to enhance the manpower resources of the state and therefore also the parent company. Such an institute can also train the increasing population of people over 60 years to remain economically self-sufficient post retirement.

Given the global economic crisis, and the need for India to structure its own developmental path, there is a strong case for setting up institutes of sustainable development. Such institutes can help reorient growth to more fully reflect resource scarcities, including those relating to energy and environment. Such institutes can also be valuable in helping to experiment with more sustainable and frugal social and economic consumption and production patterns.

The role of CSR in higher education and in mitigating the skills gap is therefore multi-facetted, with considerable experimentation, and learning-by-doing along the way. In the process, the affected individuals, companies, and society at large are likely to benefit.

The desire to change the current state of education, and of the current less-than-adequate regard for the impact of business on larger societies are, however, prerequisites.

Mukul Asher is a professor of public policy, National University of Singapore and Vikram Sampat a strategist with a Fortune 500 company. Views are personal.

![submenu-img]() Balancing Risk and Reward: Tips and Tricks for Good Mobile Trading

Balancing Risk and Reward: Tips and Tricks for Good Mobile Trading![submenu-img]() Balmorex Pro [Is It Safe?] Real Customers Expose Hidden Dangers

Balmorex Pro [Is It Safe?] Real Customers Expose Hidden Dangers![submenu-img]() Sight Care Reviews (Real User EXPERIENCE) Ingredients, Benefits, And Side Effects Of Vision Support Formula Revealed!

Sight Care Reviews (Real User EXPERIENCE) Ingredients, Benefits, And Side Effects Of Vision Support Formula Revealed!![submenu-img]() Java Burn Reviews (Weight Loss Supplement) Real Ingredients, Benefits, Risks, And Honest Customer Reviews

Java Burn Reviews (Weight Loss Supplement) Real Ingredients, Benefits, Risks, And Honest Customer Reviews![submenu-img]() Gurucharan Singh is still unreachable after returning home, says Taarak Mehta producer Asit Modi: 'I have been trying..'

Gurucharan Singh is still unreachable after returning home, says Taarak Mehta producer Asit Modi: 'I have been trying..'![submenu-img]() RBSE 12th Result 2024 Live Updates: Rajasthan Board Class 12 results DECLARED, get direct link here

RBSE 12th Result 2024 Live Updates: Rajasthan Board Class 12 results DECLARED, get direct link here![submenu-img]() IIT graduate Indian genius ‘solved’ 161-year old maths mystery, left teaching to become CEO of…

IIT graduate Indian genius ‘solved’ 161-year old maths mystery, left teaching to become CEO of…![submenu-img]() RBSE 12th Result 2024 Live Updates: Rajasthan Board Class 12 results to be announced soon, get direct link here

RBSE 12th Result 2024 Live Updates: Rajasthan Board Class 12 results to be announced soon, get direct link here![submenu-img]() Meet doctor who cracked UPSC exam to become IAS officer but resigned after few years due to...

Meet doctor who cracked UPSC exam to become IAS officer but resigned after few years due to...![submenu-img]() IIT graduate gets job with Rs 45 crore salary package, fired after few years, buys Narayana Murthy’s…

IIT graduate gets job with Rs 45 crore salary package, fired after few years, buys Narayana Murthy’s…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024

Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'

Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'![submenu-img]() Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024

Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera

Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera![submenu-img]() Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’

Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Gurucharan Singh is still unreachable after returning home, says Taarak Mehta producer Asit Modi: 'I have been trying..'

Gurucharan Singh is still unreachable after returning home, says Taarak Mehta producer Asit Modi: 'I have been trying..'![submenu-img]() ‘Jo mujhse bulwana chahte ho…’: Angry Dharmendra lashes out after casting his vote in Lok Sabha Elections 2024

‘Jo mujhse bulwana chahte ho…’: Angry Dharmendra lashes out after casting his vote in Lok Sabha Elections 2024![submenu-img]() Deepika Padukone spotted with her baby bump as she steps out with Ranveer Singh to cast her vote in Lok Sabha elections

Deepika Padukone spotted with her baby bump as she steps out with Ranveer Singh to cast her vote in Lok Sabha elections![submenu-img]() Jr NTR surprises fans on birthday, announces NTR 31 with Prashanth Neel, shares details

Jr NTR surprises fans on birthday, announces NTR 31 with Prashanth Neel, shares details ![submenu-img]() 86-year-old Shubha Khote wins hearts by coming out to cast her vote in Lok Sabha elections, says meant to inspire voters

86-year-old Shubha Khote wins hearts by coming out to cast her vote in Lok Sabha elections, says meant to inspire voters![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Man gets attacked after trying to touch ‘pet’ cheetah; netizens react

Watch viral video: Man gets attacked after trying to touch ‘pet’ cheetah; netizens react![submenu-img]() Real story of Lahore's Heermandi that inspired Netflix series

Real story of Lahore's Heermandi that inspired Netflix series![submenu-img]() 12-year-old Bengaluru girl undergoes surgery after eating 'smoky paan', details inside

12-year-old Bengaluru girl undergoes surgery after eating 'smoky paan', details inside![submenu-img]() Viral video: Pakistani man tries to get close with tiger and this happens next

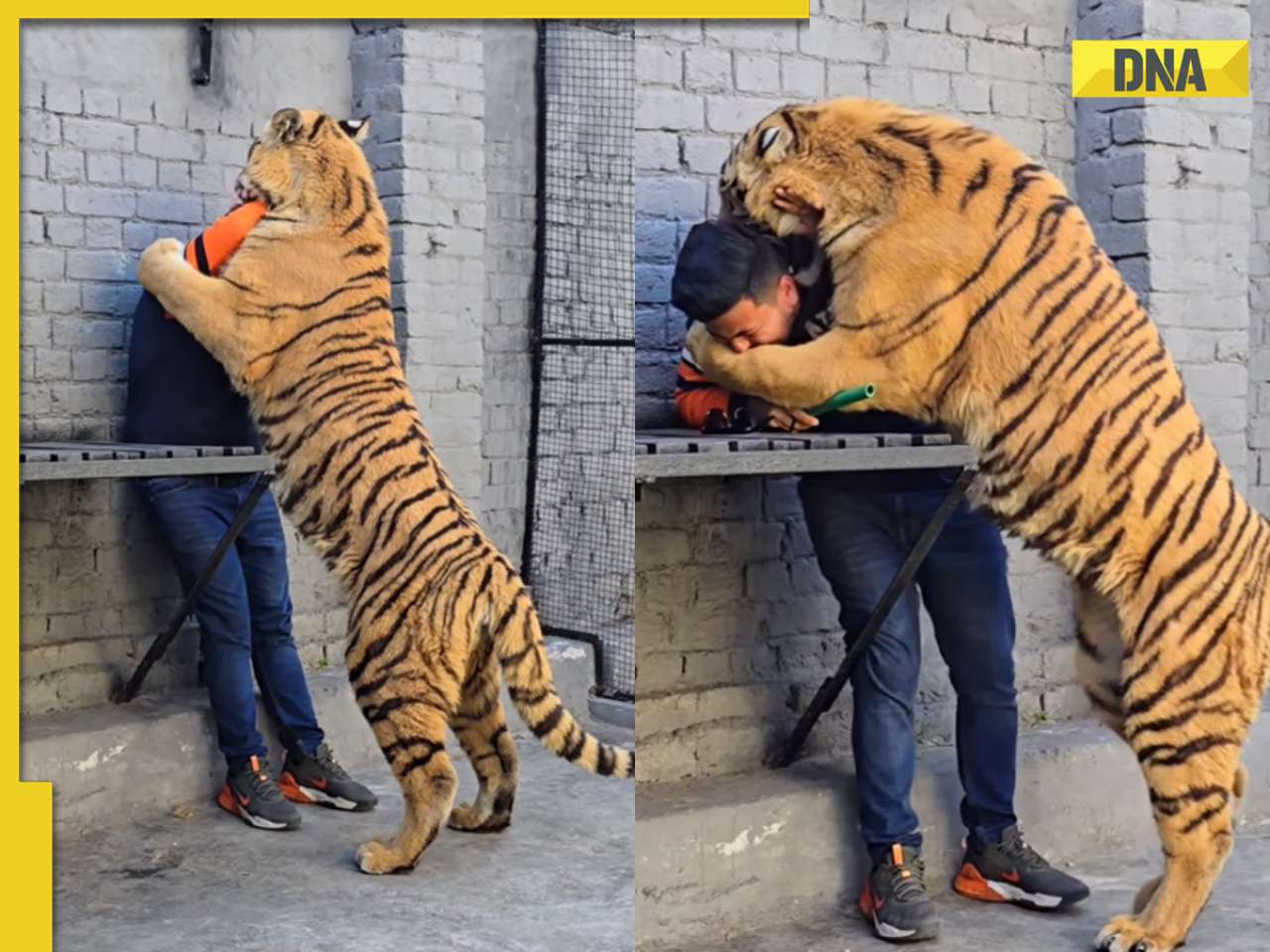

Viral video: Pakistani man tries to get close with tiger and this happens next![submenu-img]() Owl swallows snake in one go, viral video shocks internet

Owl swallows snake in one go, viral video shocks internet

)

)

)

)

)

)