Michael Pettis, a professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management and a specialist in Chinese financial markets, is an author.

Michael Pettis, a professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management and a specialist in Chinese financial markets, is the author of, among other books, The Volatility Machine: Emerging Economies and the Threat of Financial Collapse (Oxford University Press, 2001). In a telephone interview from Beijing to DNA Money’s Venkatesan Vembu, Pettis explains the risks that rising hot money inflows and an excessively loose monetary policy pose to China’s financial system and the management of its macroeconomy. Excerpts:

How much hot money is coming into China?

It’s very difficult to come up with an estimate of hot money inflows because there isn’t even a definition of what hot money is. All we can do is develop rough proxies-starting from the headline foreign exchange reserves numbers and working your way through-that give us a sense of the scale and direction of the change. And when we do that, what we end up with is unexplained amounts that have always been relatively high, but have mushroomed in the last few quarters

You’ve arrived at a figure of $257 billion in terms of “unexplained inflows” in just the first five months of 2008

That’s right, about $250 billion in “unexplained inflows” for the first five months of 2008, but not all of that may be hot money.

When you’re looking at hot money, you’re not looking at absolute numbers, you’re looking at the trend in your proxy. And if your proxy shoots up and you can’t find a legitimate explanation for it to shoot up, the assumption is that the hot money has probably shot up

Is there any parallel in developing economies for this level of hot money inflow? That’s one of the things that people are not focussing on enough. Only two years ago, when China’s foreign exchange reserves went up by $247 billion, it was the biggest one-year increase in reserves in the history of the world!

This year, China’s reserves are going up at the rate of $1 trillion; just the total amount of hot money coming into China this year is probably going to be significantly bigger than the biggest one-year increase in reserves in the history of the world until 2006.

These numbers are just huge; we have no experience with them, so it’s very hard to figure out the likely consequences.

But the big story is that China’s rapid growth in reserves, which has accelerated, is now being driven by something that is a lot less stable than the trade surplus and FDI, which is hot money flows.

What are the channels for these hot money inflows?

It’s coming in not necessarily in large blocks of money, but through a thousand different points, and in millions of small transactions...

China has three things that militate against its ability to control capital flows. First, it has long trading borders, and countries with long trading borders have a great difficulty in controlling capital flows. India has the same problem. There are just too many places that money can come in and go out. Second, China has a long history of capital controls-and, paradoxically, the longer you have capital controls in place, the more likely they are to be eroded.

What are the risks of this money floating around?

There are three things to worry about:

Overinvestment and overproduction: Chinese companies have too easy access to capital-at negative cost (less than inflation) -so the tendency is to just build more factories.

As long as the world is willing to absorb all of this Chinese production, it’s not a problem, but if there’s a slowdown in the global economy, we’ll see a rapid build-up of inventory until at some point companies start cutting down production.

Second problem with loose money everywhere-and we’re now seeing it with the sub-prime crisis in the US-is that in every single case in financial history, periods of excessive loose monetary policy have led to excessive risk-taking in the financial system. And you don’t find that out until the contraction. In Warren Buffett’s famous phrase, until the tide goes out, you don’t know who’s swimming naked. We know there’s a lot of garbage out there, but we won’t know it until there’s a contraction.

The third obvious problem is inflation

What are the risks to the banking sector?

A huge risk. You won’t know how bad it is until the contraction, and you can discount 100% whatever you hear about reserves being built up, NPL ratios going down... You can forget about all that because it’s completely irrelevant. We won’t know until it’s been tested.

What has the Chinese government done to choke off hot money flows? And how effective have their measures been?

There seems to be an internal debate between those that are more concerned about an economic slowdown and those that are more concerned about monetary excess, but it isn’t clear that that debate has been resolved.

What is the biggest macreoeconomic risk to China if it persists with its monetary excess policy? How bad can it get?

I think what’s likely to happen is that we’ll see inflation in the double digits. Once you start off that inflation process, and it gets out of control, it’s going to take a sharp contraction to break it.

What does the Chinese government really need to do?

They need to reduce money inflows into the country. The only way they can do that is by addressing the currency directly. And the only solution for addressing the currency is going to be a one-off revaluation.

By how much?

I would say 15-20%

What else do they need to do?

The currency has to go up. It will either go up in the form of a maxi revaluation or in the form of runaway inflation. That’s the choice.

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

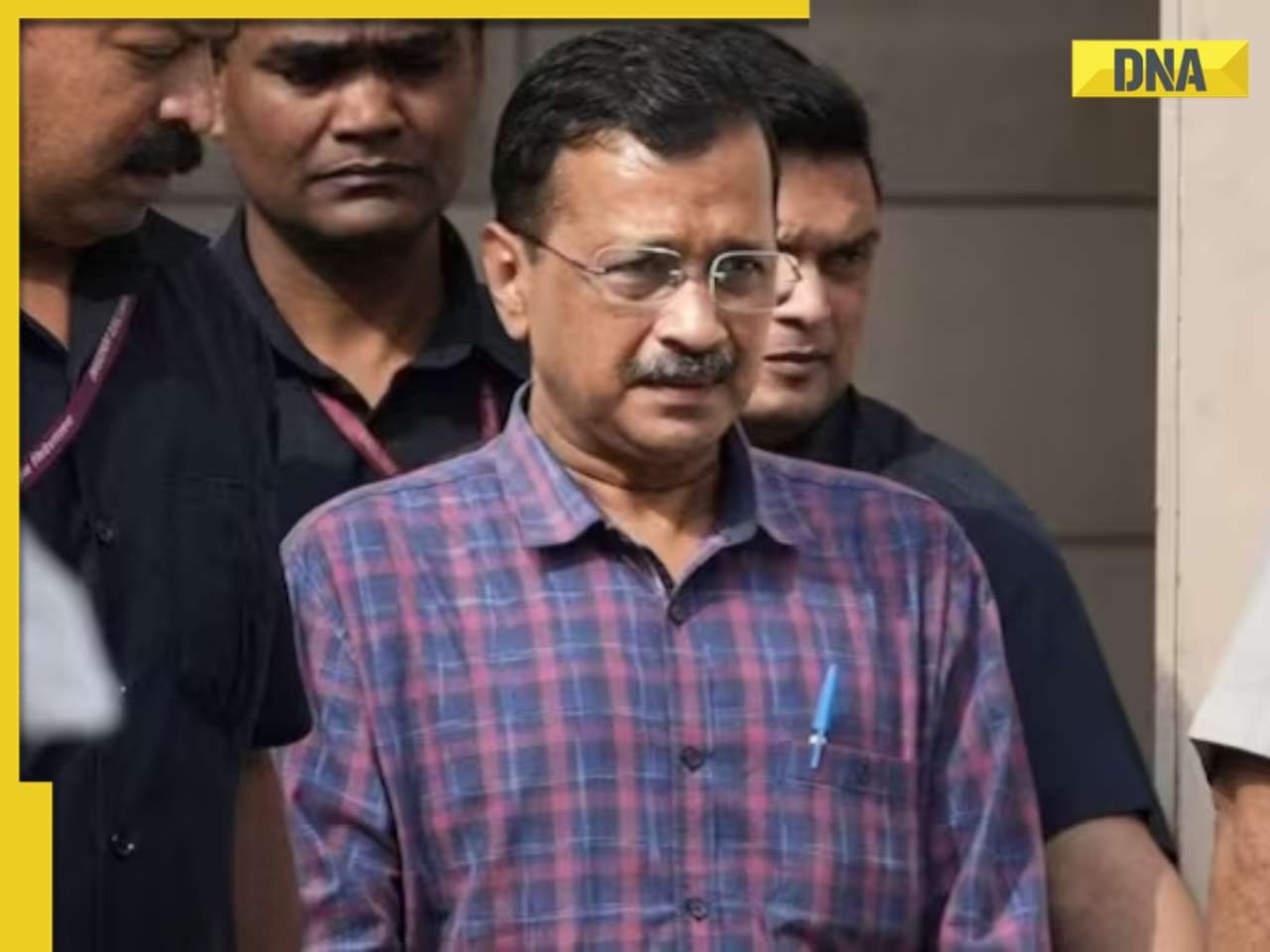

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

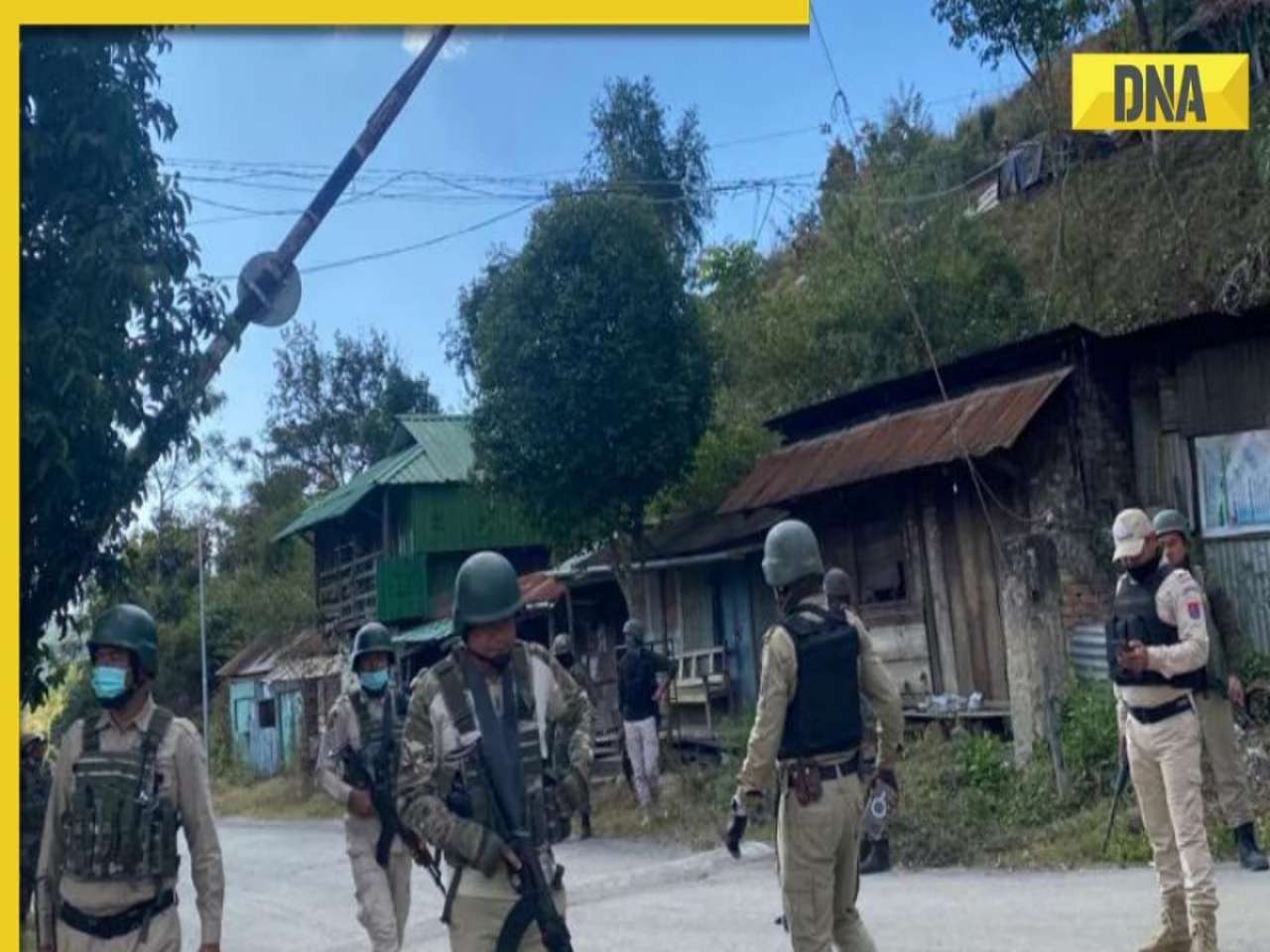

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)