With warm welcomes all round being the theme of the series so far, would both teams be better off with a return to their aggressive ways?

With warm welcomes all round being the theme of the series so far, would both teams be better off with a return to their aggressive ways?

MUMBAI: Cricket matches between India and Pakistan are never just about the cricket. The history of the two nations, both on and off the field, always makes for a little more needle; the troublemakers come to the party by agitating for their lives, while the individuals who see the chance for reconciliation indulge in expansive, explicit gestures of friendship.

The current series began with a new element however, thanks to the recent ‘developments’ in the Indian cricketers’ collective psyche.

As evidenced by the at times ludicrously contrived gestures the Indian players treated their English and Australian counterparts to in their recent matches, the Men in Blue are now trying hard to carry the fight at all times, in every gesture, word and slight phrase of body language.

Pakistan’s visit, therefore, created a situation in which the Indians could be aggressive and yet still argue that Pakistan are receiving the same treatment as any team brave enough to take India on.

Contrastingly, and of more significance, any gestures of friendship between the two, rarities in any contemporary cricket games, would have the effect of showing not just that the two teams are capable of amity, but that they are willing to dispense with their preferred game plan in the pursuit of brotherly love.

This effusive friendship has so far been the identity of this series. Of course, this being cricket, not everything has gone to plan, most notably in the exchange of views that passed between Gautam Gambhir and Shahid Afridi in Kanpur.

The occasional lapse into over-competitiveness cannot erase all the smaller instances that have emerged in the matches; batsmen are greeted by fielders, batting landmarks are applauded in the field, balls gently tossed back to the opposition.

More than these have been the wide smiles on the faces of all the participants, which have regularly become laughs as jokes are passed between bowlers, fielders and batsmen.

Peace and friendship reign for now but, unfortunately, it was not always thus.

Of the many instances of players clashing in these matches in the past, a few stand out from the rest. India versus Pakistan at the World Cup is roundly regarded as the biggest match in World Cricket, and it certainly had a tumultuous start.

The first time the two sides met in the tournament was in 1992 in Sydney. Javed Miandad took exception to Kiran More’s chatter from behind the stumps and followed an angry exchange with a surreal imitation of More’s ‘kangaroo jump’ appealing style, but the potential humour of the situation was lost in the sense of ugly conflict.

Even today, More, who accepts that it was his words that sparked the fight, explains the incident in simple terms: “the situation was tense because it was an India-Pakistan match. Everything was at a feverish pitch at that point of time.”

The same excuse could have been used by Venkatesh Prasad in the 1996 quarter final, when he less than sportingly pointed Aamir Sohail back to the dressing room after he bowled him, in imitation of Sohail’s own gesture after he had hit the previous ball for four.

Whether the change has come from the players or the situation at large, that excuse seems much less acceptable now: the mere fact of the match can no longer justify behaviour that would be unacceptable in contests with other protagonists.

The behaviour of the crowds has often been a greater thermometer than the players’ conduct for the way in which political tensions have spilled into the cricket field.

The 1999 Calcutta test match was a particular low point, as the game had to be finished in an empty stadium after the crowd proved incapable of dealing with the idea that Tendulkar can be run out in unfortunate circumstances without cheating being involved.

The mercurial nature of the fans’ behaviour emerged just a few years later, when India arrived in Pakistan for the ‘Friendship Tour’ in 2003/4.

The rapturous reception received by the Indian fans is still warmly remembered, and the repeated sight of the two flags being sewn together and waved in an orgy of positive feeling felt designed to send tingles down the necks of anyone who believed in a positive future for the region.

The thawing of relations as seen since that tour points to the gradual maturation, on both a sporting and national level, of the big players on both sides.

There is a counterpoint to all of this bonhomie however. Classic sporting encounters rarely consist of two teams cracking jokes with each other, and then embracing. The argument that the lack of aggression leads to a lack of contest is a valid one.

That the Pakistan players came to Virender Sehwag’s home to commiserate after his father passed away lends them credit as human beings, but will not affect the cricket they produce.

Likewise Shoaib Akhtar posing in Indian policemen’s clothes or Yuvraj inviting both sides to his house to celebrate Diwali together.

Players at each others throats will not necessarily play any better cricket, but their commitment to the cause of victory may just rise in commensurate with their tempers.

The choice that Sub Continent cricket has to make, then, is between fiery, exciting war or warm, cosy peace.

Peace may seem to be the sensible option, but for any mischievous fans who still long for the days when India Pakistan matches resembled a cross between trench warfare and a Marx brothers film, it should be remembered that, at some point, the Sreesanth factor is sure to come into play.

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

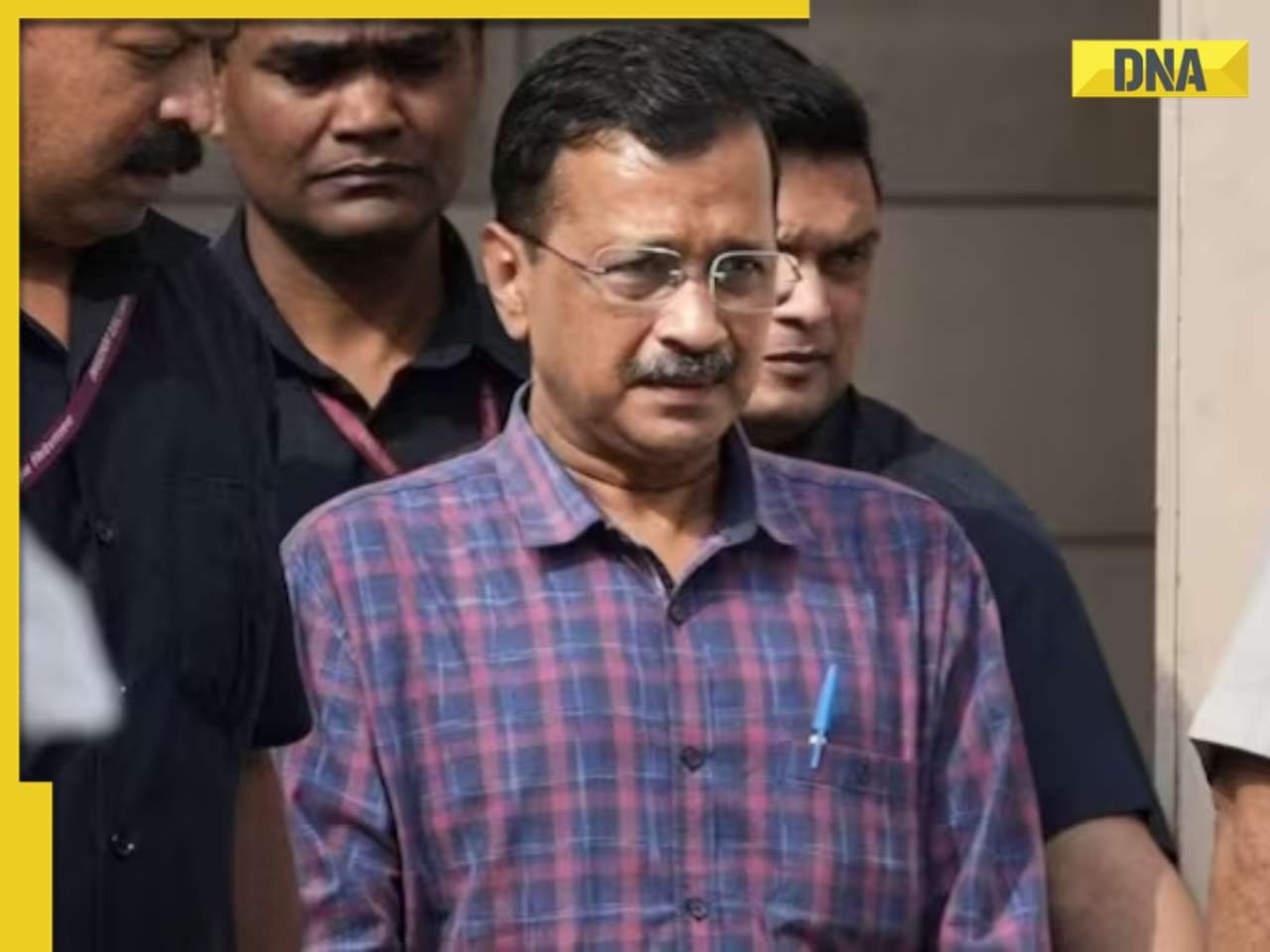

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

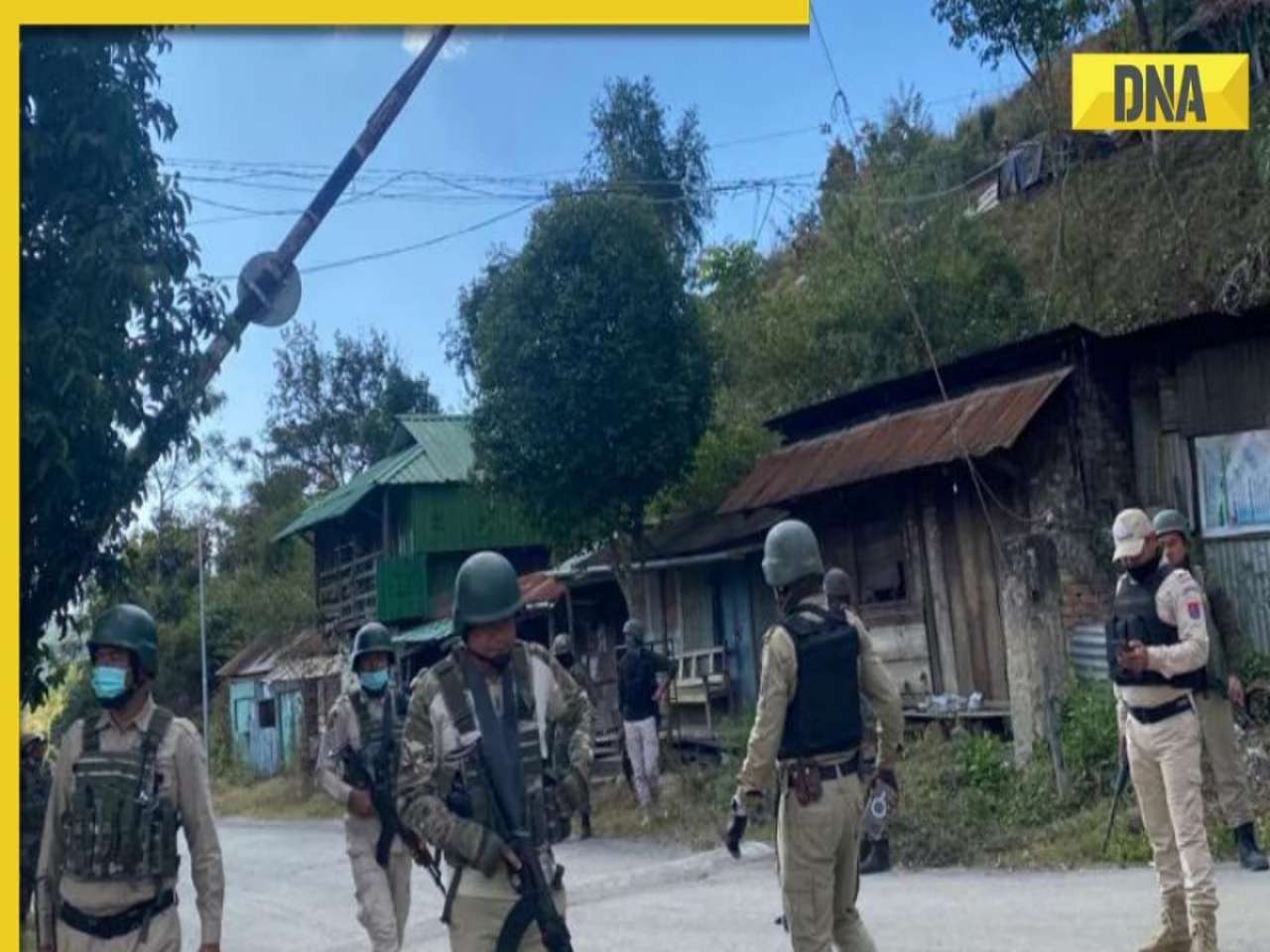

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)