he Mumbai constabulary’s condition is worse on that front. Their houses leak, have minimal infrastructure. DNA Team visits some of these buildings and find the conditions pathetic.

Painted in off-white and red, the humble police chawls in Worli, Naigaum and Byculla nestle between high-rises and plush residential complexes. Called police quarters, these BDD chawls — about 30 of them — house police personnel from the rank of a constable to an assistant sub-inspector.

It is here that a cop retires after a day’s hectic investigations and stressful bandobast duties only to grapple with a sea of waiting problems.

So gruelling is his average 12-hour shift that he has little time to think about the problems his family struggles with. With a measly salary of Rs 6000, perhaps the only redeeming feature — if it can be called that — of his existence is his entitlement to a residential quarter as soon as he/she completes initial training.

The conditions at the police quarters is pathetic. The tenement, a mere 180 sq feet of crammed space, suffers from leaking roofs, cracked walls and stinking toilets.

“Monsoons are particularly bad,” says the wife of an assistant sub-inspector, cleaning utensils at her ground-floor home in Nehru Nagar police quarters. “After the 26/7 deluge, I dread the prospect of one every time,” she adds.

She is not exaggerating. When rains wrecked havoc on that day, the ground floor quarters in Nehru Nagar almost floated in waist-deep water. “We lost most of our wooden furniture during the deluge. Our walls developed cracks,” she points out.

The maintenance of the police quarters comes under the purview of the Public Works Department committee of the State Government.

“The conditions are appalling. Even for a minor repair, we have to repeatedly follow up with PWD officials,” says a constable attached to Sion police station. He is among the many who have plenty to say about the conditions there, but do not have the nerve to come on record for reasons of reprisal from the department.

With the residents in a harried state, it is a case of unity in diversity. They bond with each other and readily reach out when faced with difficulties.

“We lent the plastic sheet we had to a resident of our neighbouring building since the roof of our quarter was repaired for leaks,” said the wife of a constable, attached to Ghatkopar police station, adding, “since most problems are common, we devise and share solutions.”

Often, desperate situations brook desperate measures. The common problem of space crunch and lack of privacy is overcome by youngsters being given a separate room for study preparations while parents go to the neighbouring house to sleep.

“It’s fun though forced by the situation. We have great time trying to explain lessons to each other,” says a 23-year-old, who also works as a driver in a private company.

The residents suffer from perennial water shortage. Each quarter has to make do with only 25 minutes of supply through the day.

“In this short time we are supposed to store water that will suffice for the day. This has to take care of cooking and the daily chores,” said a police constable from Matunga police station.

A significant pattern emerging from the children of the lowest rung of the Mumbai police is they aim at looking money-making opportunities at a much earlier age. Many eye the BPOs even before turning graduates in their bid to ensure better living.

“I want to earn a decent salary and move to a bigger house,” says the 17-year-old son of a constable attached to the Nirmal Nagar police station. His sentiments are echoed by the school-going son of an assistant sub inspector of Byculla police station: “When I look at the houses of some of my friends, I feel embarrassed.”

The cops are also aware of the flip side of their sordid life. Conscious of the sky-rocketing real estate prices in Mumbai, a constable at the fag end of his career sums it up, “Thanks to my job, I could raise my family in a convenient area like Dadar. If not for my job, this would have been impossible,” he says, philosophising, “there is nothing like a no-problem situation. One should learn to tide over them and convert them into opportunities.”

While the idea of providing accommodation to the constables in a city especially where the land sells at a premium, is noteworthy, the fact remains that these quarters are far from being anyone’s dream home.

The only alternative that the constables have is to move from their dilapidated quarters to the squalid slums of the city. This move, however, is like “jumping from the frying pan into the fire”, as one constable puts it aptly. For slums come with their own set of problems.

Issues like legality of the slum houses, lack of space and privacy, unclean toilets, await slum dwellers in their homes. “Many slums are notoriously unsafe, even for the police,” confessed a constable, living at Byculla.

Health, education and sanitation in slums are prime concerns. “We work hard to give our children good education, so that they get better-paying jobs. I don’t want my child to fall into the company of drug addicts and petty criminals who reside in slums,” said another constable. “Moving to the slums is a step backwards,” agreed an assistant sub-inspector a resident of Worli’s BDD chawl.

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

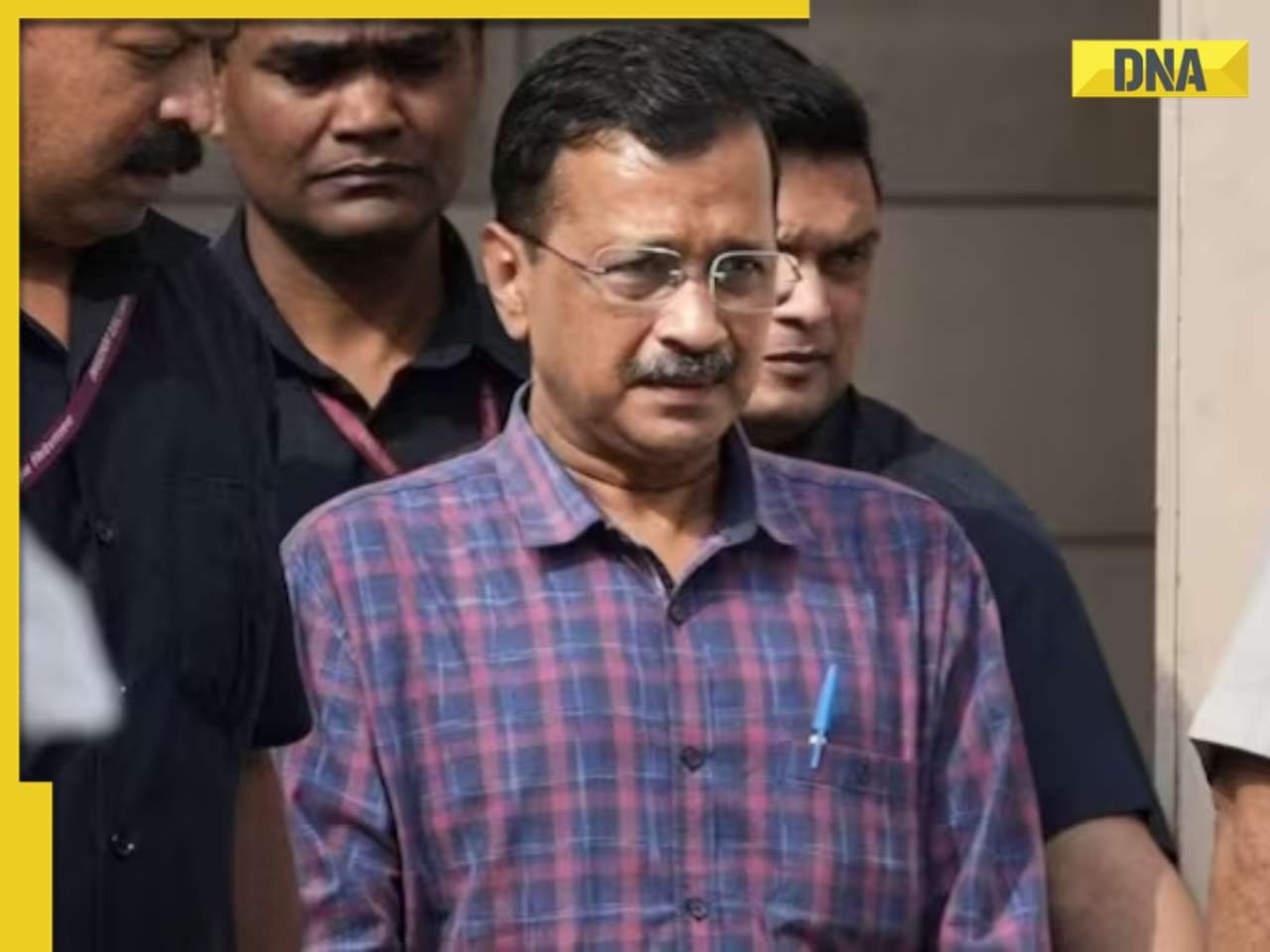

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

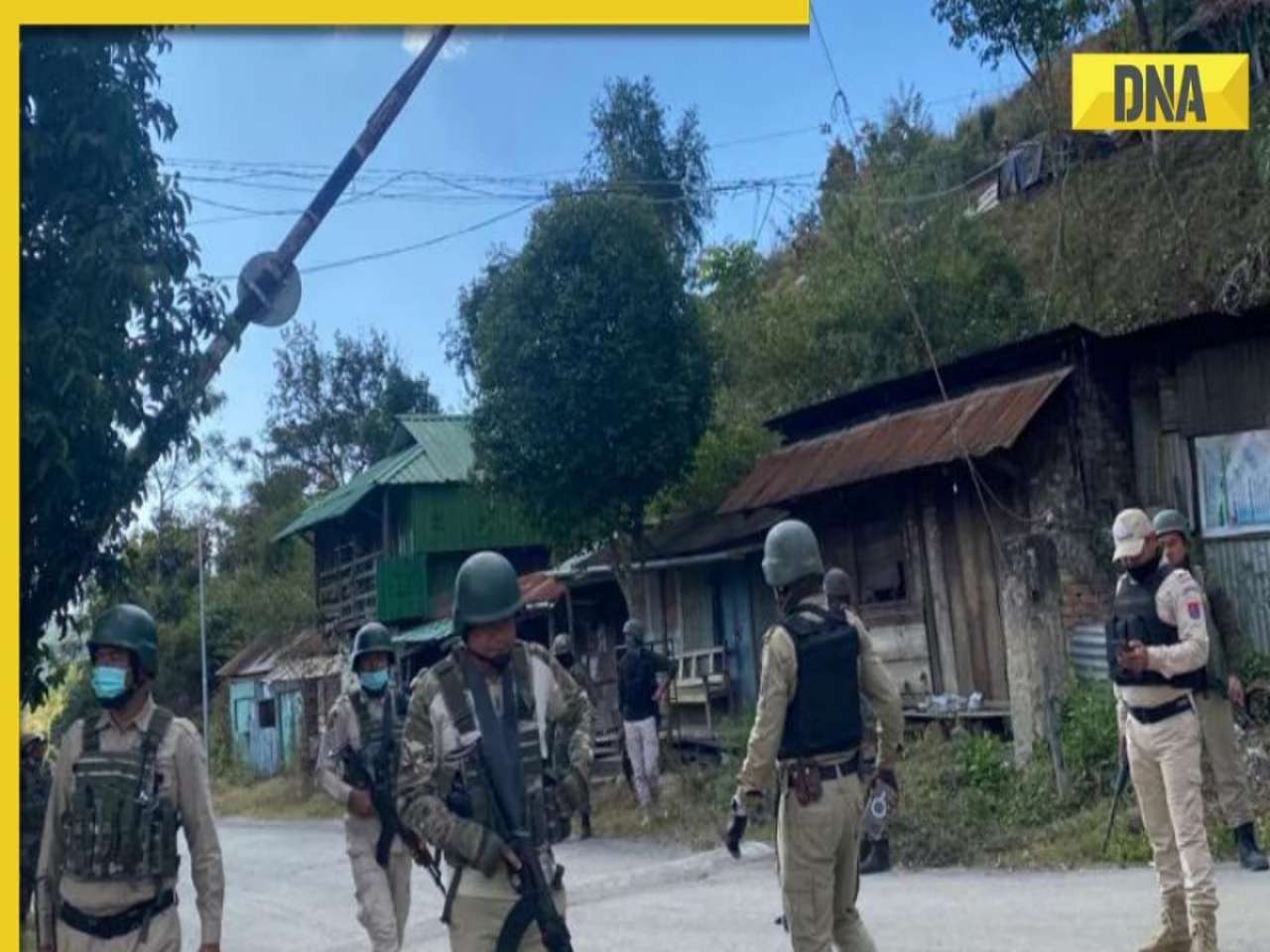

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)