Yes, there will always be a Bombay, says Gautam Benegal. It simply may not be in Mumbai anymore. Yes, the spirit of Mumbai is alive. But not bound to this place

Way back in my teens, reading those Louis L’amour westerns, one thing appealed to me greatly. It was the description of those campfires where strangers gathered and drank coffee — each one not knowing the other’s name, swapped stories, and moved on. None displayed curiosity about the other’s past. It was the frequent reiteration in those books that all kinds of people rubbed shoulders in the West: horse thieves, scholars, bootleggers, scientists, musicians —and the wrong kind of questions could get you killed.

A man’s past was behind him and done with when he went to the West. When I came to Bombay in the late eighties, I was therefore thrilled to be given this advice by my ‘import-export’ roommate on my first night, in a boarding house in Chembur: Don’t stare at a man’s eyes directly in a crowded local train — he could turn out to be anybody. This was my Wild West where anything could happen and my destiny was mine alone.

There was joy in not taking money from my father (who didn’t have any in the first place) and fulfillment in staying as an illegal sub-tenant in the Antop Hill government quarters or the PNT Colony at Sahar. Dealing with rat-faced brokers, eating street food (that now finds hallowed place in the so-called Food Guide) and often going hungry opting for a quarter of Old Monk instead.

On Sundays, I’d walk the length of Fort and Churchgate, browsing the pavement bookshops, blow a major part of my week’s earnings downing beers in an Irani and take the Harbour Line home. For back then, Bombay was not just a place to make it — it was freedom. To live on one’s own, with no societal obligations, free from the opinions of others and to explore dark and tantalising corners.

This was a port city, an everyman’s city, a frontier town and a bachelor’s paradise. I stayed with three elderly Sindhi brothers once in Bandra as a PG — they were brokers who had seen good times once but were now broke. The eldest had, in his heydays, bought an Impala car and on the very first day, not knowing how to drive very well, smashed it against the society’s gates. It went as scrap that very day. No regrets. Coming from a background that made thrift into a religion and risk into a four letter word, I learnt new words like bindaas and phrases like himmat mat haro. And no one ever called a struggler a loser even if he had lost.

A struggler was an entrepreneur and there was a bond. But as I was revelling in the backbreaking work in an animation studio at Mahim for a pittance, gadding about in the local trains, exploring the charms of Sion Koliwada and the narrow bylanes of Borabazar street, I was missing out on one essential point. In those fictionalised accounts of L’amour, the West was frozen in time and the cowboys and gunmen never grew old. There is nothing as impartial, meaningless and amoral as a bomb.

There is nothing as sordid and mundane as a coward. In 1993, the meaninglessness, amorality and sordidness of lesser men leached the colour from the city, robbed it of its magic and left us with a husk called Mumbai. And if that wasn’t enough, soon our trees would go, and a thousand malls and department stores would bloom in place of the picturesque wadis and the hundred-year-old chawls.

I now cope with my Xanadu gone, no longer a city of dreams — just a piece of real estate to be sold and re-sold repeatedly. Twenty-one-year-olds who wandered aimlessly in this new world and browsed through pavement bookstalls will be called losers — and rightly so. For the next wave of migrants have not come with stars in their eyes like a Dharmendra or a Yusuf Khan struggling from a chawl.

They are a steady, practical lot; rich landowners drawn by the real estate boom or would-be young TV stars and starlets with the solid backing of feudal family wealth, starting their careers from 2BHK pads in Lokhandwala and Yari Road. Conservative and traditional deep inside but with the veneer of modernity quite like the McAloo burgers they prefer.

I watched as Dr Salim Ali’s beautiful bungalow was pulled down and concrete took its rightful place. The old houses of Bandra, Santa Cruz and Khar with their quaint, old names fell into neglect and legal disputes. In Lower Parel, under the shadow of the malls and highrises, are small shanties that line the streets. Entire families wait here for compensation from the closed mills and eke out a living by selling street food. They are the collateral of someone else’s boom town. I find the remnants of the past in Central and South Bombay.

And the new brash Terminator 2 avatar in North Mumbai. Right opposite Crossroads Mall on Tardeo Rd is a Parsi colony — understated, almost apologetic. It is easy to miss it on your way to the Haji Ali signal. Old men and women peep out from behind faded curtains timorously at the huge blazing mall. It is hard to believe that these are the people who ruled Bombay once.

It was the rich tapestry of different communities that was so attractive, that gave this island its special place. My south

Bombay friends used to joke, “It is not part of India.”

From Pancham Puriwala’s mouthwatering puris to Martin’s sausages off Colaba Causeway. From vintage cameras to the latest Nintendo games. From Mani’s sambar in front of Ruia College to the heaps of liver, kidneys and assorted meats at the Mohammed Ali Road stalls. From the amazing Novelties Regd.

Shop on Peddar Road with its ancient curios, to the garish bric-a-bracs of the Causeway. All India, yet definitely not part of India — for where in India would you find such inclusiveness and so much variety within a few square kilometers? This was Bombay — not the city but the concept. Whoever’s soul wishes to be free and to be all those things that liberate us from pettiness will always wish to go West. To find a Big Apple or a Big Alphonso. Away from hometowns and biradaris that bind us down.

But when the concept died, the city died. We let the small minds decide the fate of Bombay. One by one these spaces are being taken over by rows and rows of fast food centres, hideous garment and furniture shops, malls and glass fronted call centers. There is no nightlife as that would offend the sensibilities of the gentleman from Sangli or Jaunpur or whatever. He would rather not blend into this place, but bring his own baggage of prejudices and beliefs with him. The entire city and its culture is being worked over with the twin brushes of uniformity and conformity. Office buildings? Glass fronted. Songs? Hindi. Interiors? Saas bahu serials.

Food? Punjabi-Chinese-South Indian. Entertainment? Malls. If you want to be different then you now belong to the niche market. Try the five star hotels for the kind of food you took for granted yesterday. Try the NCPA on the far tip of the island for the kind of programmes you grew up enjoying, and had ready access to close to home.

Yes, the Mumbai spirit is very much alive. But it is a free spirit and not bound to this place and time. A process of reverse migration will begin where many of the educated and the young who are in a position to, will opt for quieter, more sensitive places. Places where they can breathe and not have to dumb down in order to survive. There will always be a Bombay. It simply may not be in Mumbai any more.

![submenu-img]() ‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…

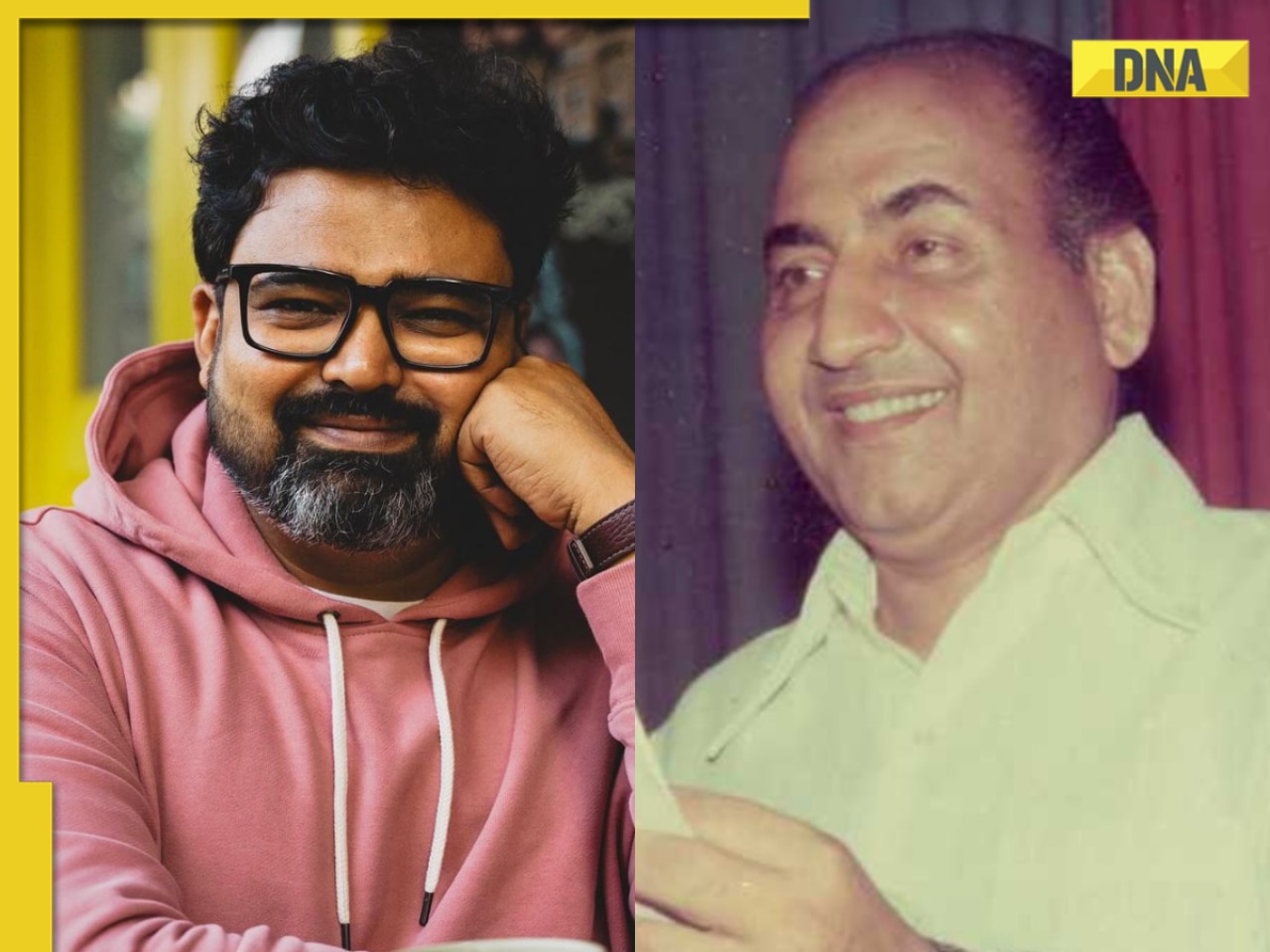

‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() 'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot

'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot![submenu-img]() JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy

JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy![submenu-img]() AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...

AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’

Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’![submenu-img]() Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..

Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore

Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...

Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals

IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() 'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket

'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket![submenu-img]() 'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024

'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians

LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)