Congratulations are in order for the Central government for coming out with the minimum support prices for various kharif crops before the commencement of the season.

Congratulations are in order for the Central government for coming out with the minimum support prices for various kharif crops before the commencement of the season.

But whether the across-the-board hike will translate into a significant leap in production remains to be seen.

In this, the behaviour of the south-west monsoon, in terms of spread and quantum, over the four months ending September will play a crucial part.

At least, the officialdom will not be faulted for not playing a catalyst’s role in the effort to give a big push to the harvest of rain-fed crops.

Still, will the price magic alone will work in imparting dynamism on the production front?

Doubts are in order, for, in respect of most crops, a varietal breakthrough is no where in sight and we have become chronically dependant on imports for much of our requirements of pulses and edible oils while in coarse cereals, to say we are languishing would be an understatement.

To the common man, who is buffeted by inflation, the major worry is that whether, in its eagerness to seek the cooperation of the farming community to raise kharif output, the official policy may rekindle inflation.

Prima facie, a steep increase in various commodities may be an invitation to a price spiral, but if the harvest turns to be bountiful, aided by an excellent monsoon, there may be a respite on the price front.

But, first, a perspective on the agricultural scenario. We have two broad farming seasons, with kharif season commencing with the onset of the south west monsoon in June.

This season comes to close by September and the new crops start arriving in the markets from October.

It is for these crops the government has just announced what price it would be paying if the farmers supply the produce to the procurement agencies.

Roughly, more than half of the annual agricultural production is accounted for by the kharif crop. The main kharif commodities are rice, coarse grains like jowar and bajra, oilseeds, cotton and pulses. Some of them are cultivated in the rabi season - the crops are sown in November and harvested in April- but wheat and gram are the principal rabi crops.

When the new strategy of agriculture was adopted in the late sixties, a giant leap in output was achieved in rice and wheat. To insulate the farmers from a precipitous fall in prices due to a bumper harvest, the government adopted a policy of prescribing a set of prices at which it would be buying commodities. The interests of farmers were sought to be protected and they were motivated to continue cultivation of these crops.

This strategy paid dividends in that, both production and procurement of rice and wheat were on a rising curve, until recently, when a sort of plateau seems to have been reached even in the case of these crops. The spread of hybrids revolutionised the cotton economy, though superior varieties of cotton are yet to be produced to match our needs.

However, to put it bluntly, for most of the other crops - coarse cereals, pulses and oilseeds, the announcement of a procurement price - or minimum support prices as both are used interchangeably in the Indian context - is more in the nature of a charade. Year after year, the Centre not only fixes the support prices, based on the recommendations of an expert body - Commission on Agricultural Costs and Prices - but also hikes them substantially.

This year too, in all cases, there has been an upward revision and in respect of pulses and maize, ragi, jowar and bajra, the increase has been substantial. Yet, in the past, there has been no worthwhile procurement and this time too, the result is unlikely to be different.

Why? The reason is simple. The policy of incentive pricing will work best only when there is also a production revolution. In oilseeds, inferior cereals and pulses, a breakthrough is yet to materialise and hence no success worth the name in regard to procurement too.

The worry is whether, despite the handsome increase in paddy prices, procurement effort will meet with success in the ensuing kharif season. In the case of wheat, we have seen how there has been a reversal of fortunes and we are forced to import wheat in large quantities.

In rice, we are better placed in that, much of the procurement takes place in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh; in these states, rice is not the staple food of the people and rice is more or less a cash crop that is offered to the procurement agencies to shore up the inventories.

For this reason, the hike may be beneficial but success hinges on the size of the crop which, in turn, depends on monsoon performance. For cotton too, the outcome is related to the behaviour of the monsoon.

Prima facie, inflation may rear its ugly head due to the generous increases in kharif procurement prices, unless rising costs of cultivation are offset by productivity gains.

On this score, the progress seems to be very tardy. If a bountiful monsoon materialises and gives a big boost to kharif output, supply side constraints may get a breather and inflationary psychosis take a beating.

If inflationary expectations are lowered, the impact on the price situation may be benign, despite the officially sanctioned procurement price hikes.

And, this time too, there is an additional justification in that government has acted on the recommendations of the Commission on Agricultural Costs and Prices, making a departure only in two cases.

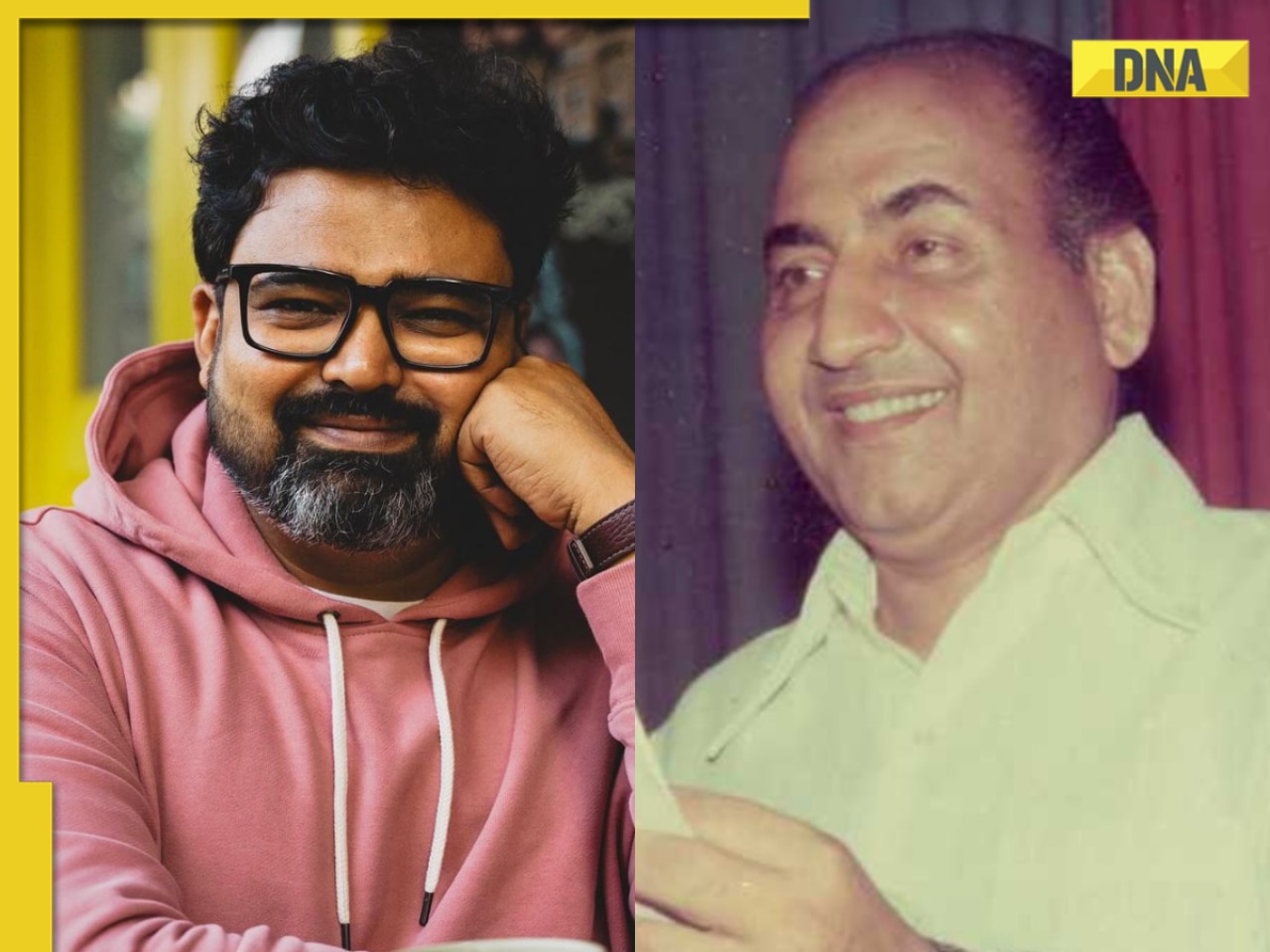

![submenu-img]() ‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…

‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() 'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot

'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot![submenu-img]() JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy

JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy![submenu-img]() AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...

AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’

Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’![submenu-img]() Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..

Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore

Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...

Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals

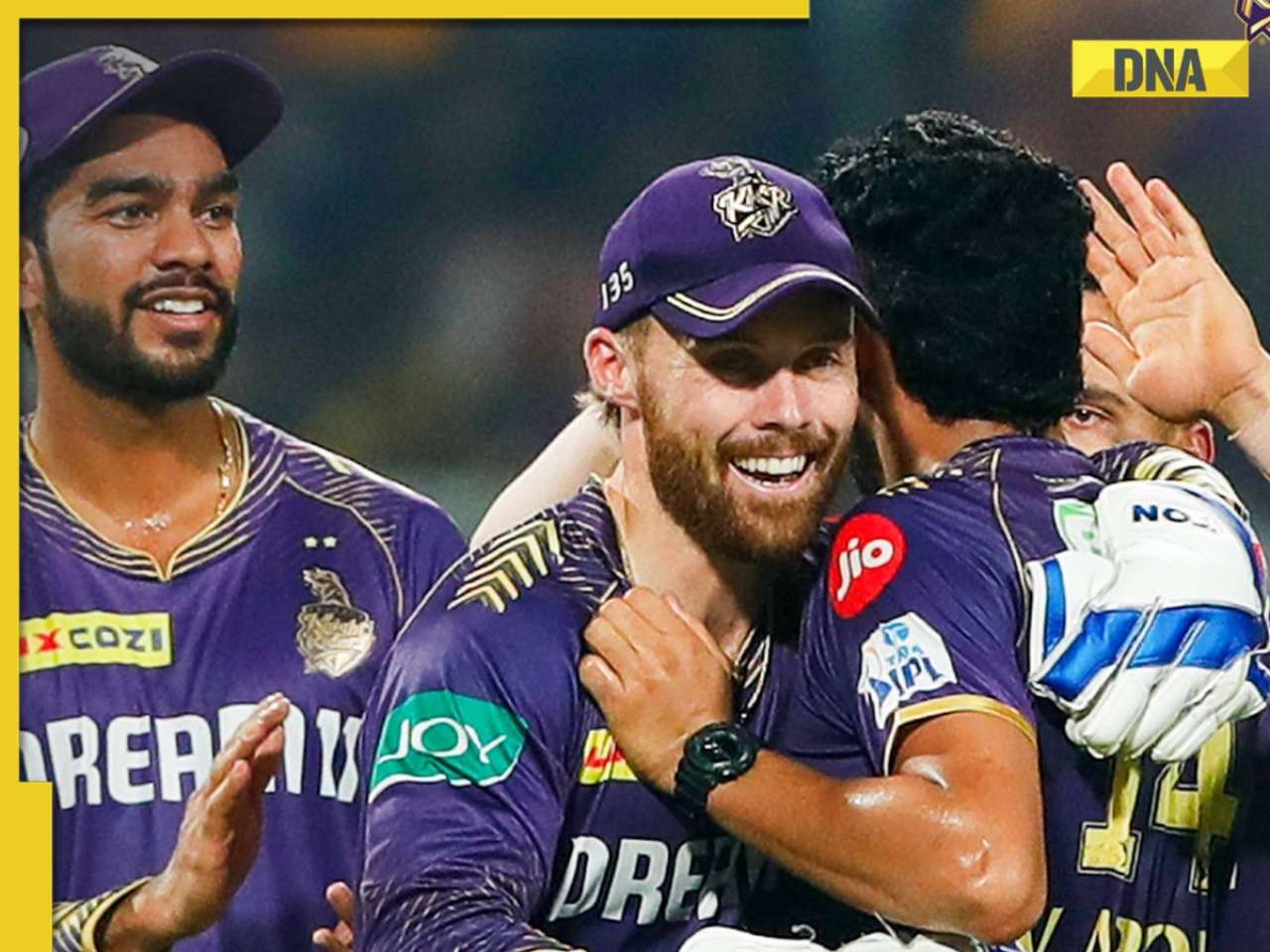

IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() 'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket

'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket![submenu-img]() 'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024

'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians

LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)