According to a report, for MNCs in China, it is now a challenge not only to recruit the best people, but also to develop and retain them.

Phillis Ho is on a career high. After two job hops in under five months, the Shanghai-based account executive in a multinational advertising agency has seen her salary more than double; and although she’s told headhunters she’s not looking for another change, her phone just hasn’t stopped ringing, with ever more enticing offers.

Ho is the beneficiary of a new kind of China syndrome: an acute shortage of talented managers that is severely cramping the operational efficiencies of multinational corporations (MNCs) that are drawn to the ‘billion-three’ market. (‘billion-three’ is the colloquial allusion to China’s population of 1.3 billion).

A recent executive action report from The Conference Board, the leading business research organisation, noted that for MNCs in China, “it is now a challenge not only to recruit the best people, but also to develop and retain them.

Although the number of young people earning undergraduate and graduate degrees is increasing rapidly, these newcomers to the workforce often lack the practical experience and softer creative and leadership skills required in the business world.”

A 2005 report by McKinsey Global Institute, The Emerging Global Labor Market, found that global managers consider only 3 per cent of graduates in China with a general degree to be employable.

Judith Banister, who co-authored the Conference Board report, told DNA that the talent shortage reflected China’s “growing pains problem”.

She adds, “China’s economy has been booming for a quarter century now, and all the things that are needed for a rapidly growing economy tend to run short when it’s growing so fast.”

That shortage, particularly in the area of human resource, is “pressing on the limits of what China’s able to do,” says Banister, who has authored several research papers and publications on the correlation between demographics and the national economies, with particular focus on Asia.

The Conference Board report notes that China’s population, including the labour force, is ageing rapidly, but the expanding number of people aged 40 and over is not well educated and does not constitute an adequate pool of talent for companies.

Of China’s employed population aged 40-44, only 2.6 per cent have a university or higher degree, and the proportion is only 1 per cent of those in their late 40s and 50s.

“Conversely, the number of people in their 20s and 30s is shrinking over time, but this is the part of the population where talent is located in China today.”

This talent shortage, says Banister, is beginning to impact some MNCs, particularly the smaller ones. “If they cannot compete well enough with the top MNCs for the talent which is in short supply… they get knocked out of the China market.”

However, the steep decline in fertility rates in China has been accompanied by a sharp rise in the quality of health and educational attainment of children, notes the Conference Board report.

“These young people are often hungry for responsibility, position and the trappings of success. A lot of young Chinese managers… will readily move between employers in order to get a bigger salary, more status, and more opportunities.” This, the report adds, “is one of the reasons why staff turnover rates are very high in China.”

A recent survey by global consulting firm Watson Wyatt Worldwide showed that Chinese workers are far less satisfied with their pay and benefit packages than workers in the rest of Asia-Pacific and in the United States. This, the survey noted, “could pose challenges for multinational employers in China’s rigid labour market.”

Says Robert Wesselkamper, director of international consulting, Watson Wyatt: “The challenge for employers to create monetary compensation and benefit satisfaction for

Chinese workers is great.

Raising pay will not solve this problem. By demonstrating how pay is determined and the value of a total rewards package, companies can help employees understand how financial return is only one part of a larger compensation strategy.”

Yet, despite the acute talent shortage and the cost of finding and retaining talent, the outlook in China isn’t bleak, emphasis Banister. “Many MNCs in China are finding creative solutions to their problems by partnering with universities to tailor their programs so that graduates are more to their needs — with great success, in some cases.”

Other companies give a lot more leeway to their HR personnel in China so they can adjust to the market more rapidly, and do whatever it takes to get the people they need.

But more importantly, according to Banister, the Chinese government understands that it needs to improve the situation, and is critiquing its educational system to emphasise innovation, rather than rote-learning as in the past. “What they’re trying to do is to change the mindset of the educated Chinese people and get them to debate and innovate, and acquire teamwork training and leadership skills.”

In the late 1990s, China started establishing many new universities and graduate programs and expanded the number of places in existing universities, giving many more students opportunities for advanced education. This resulted in a steep increase in the number of graduates from 2001 onward, reaching a record 4.13 million graduates in 2006, a 22 per cent increase from the year before.

The number of MBA programs too has shot up in recent years, to 230 in China.

“You get a lot of MBA graduates,” notes Banister. And while she acknowledges that the quality of graduating students isn’t uniformly good, “in some cases — for instance the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai and Shenzhen — they are world-class.”

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

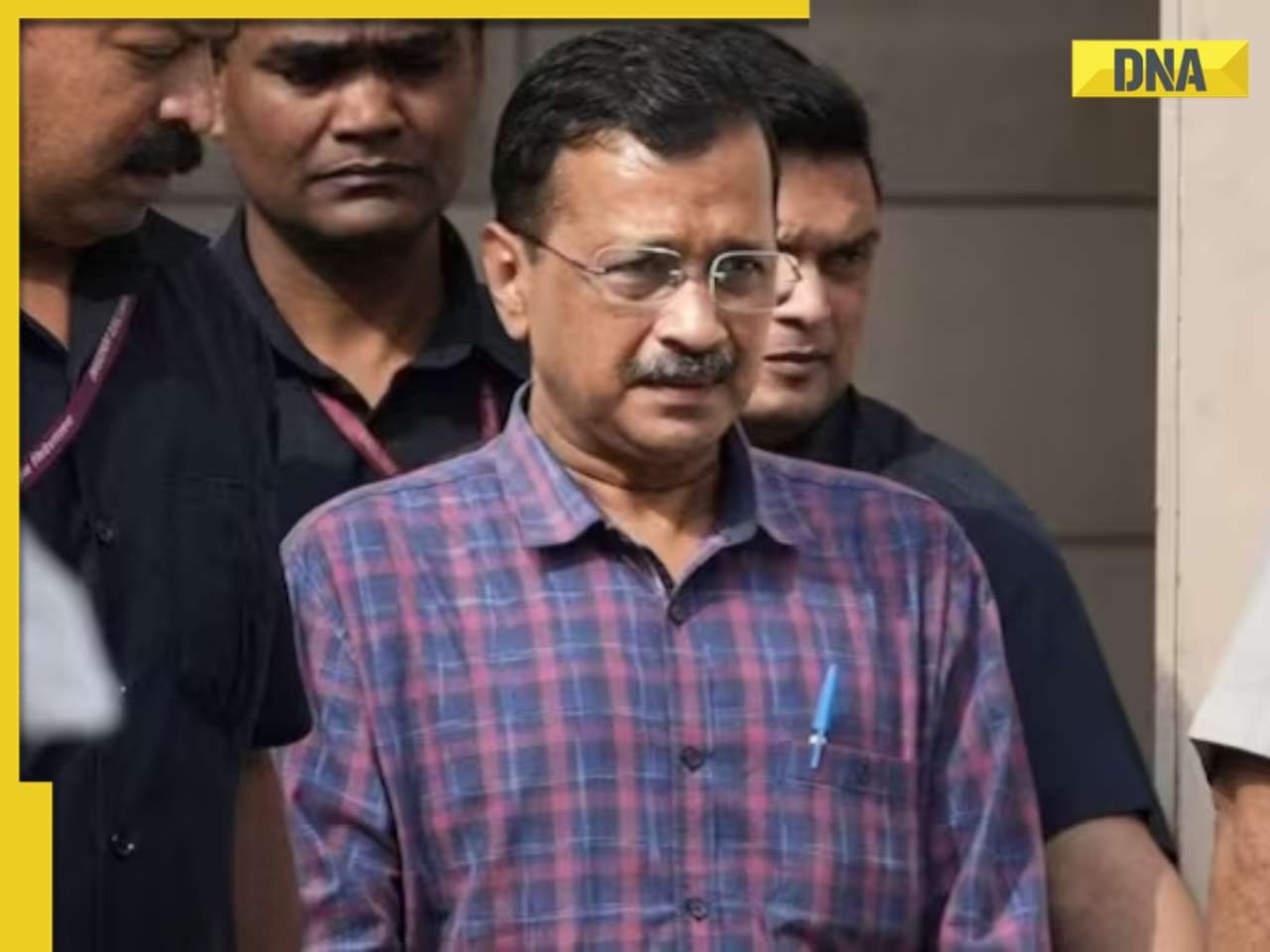

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

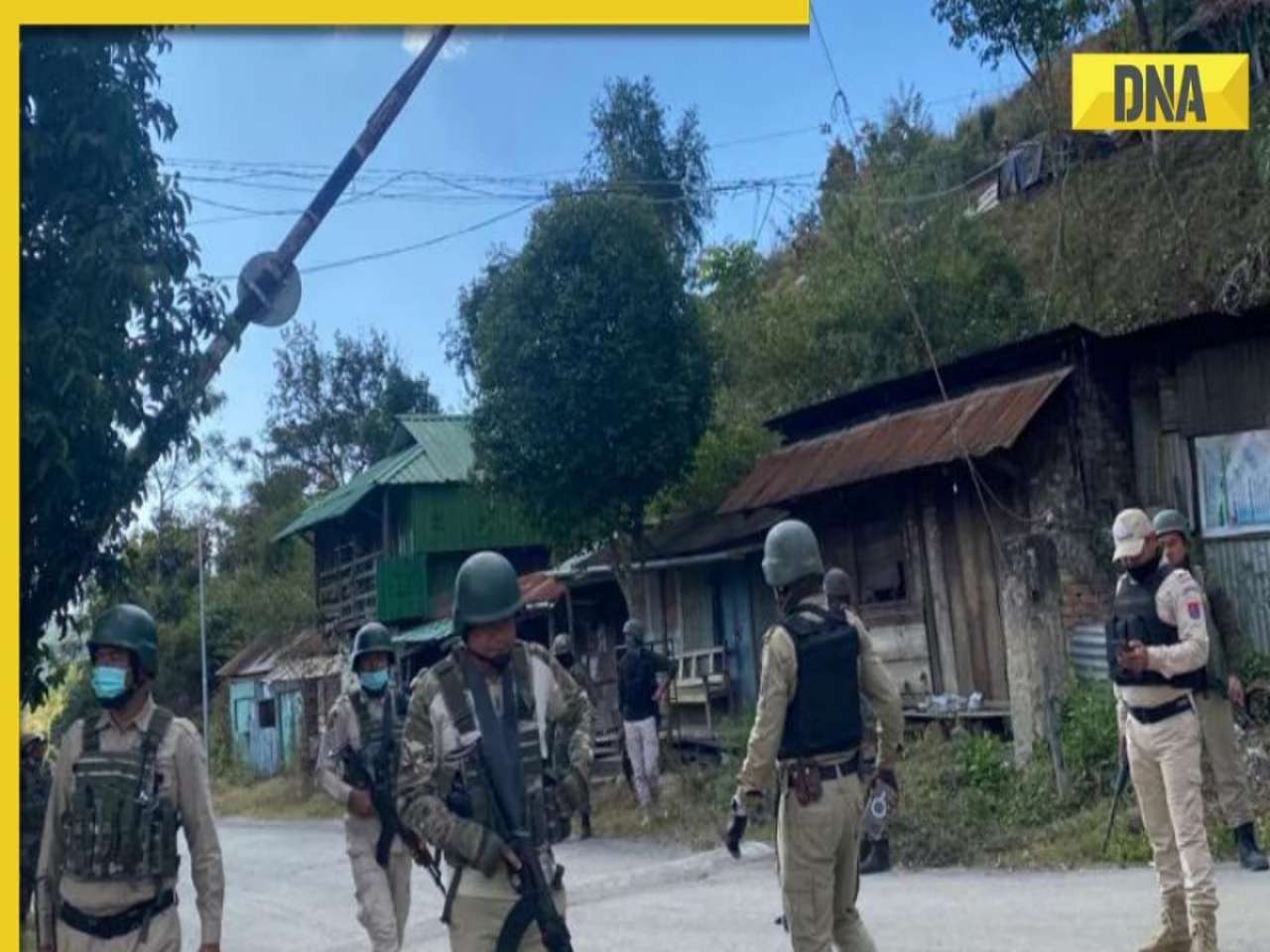

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)