India’s potential for cheap medical trials has been aggressively marketed. But experience of the subjects has not been satisfactory.

India’s potential for cheap medical trials has been aggressively marketed by research organisations. But the experience of the subjects, who were not adequately informed in most cases, has been anything but satisfactory

Parshuram Marathe’s (name changed) ignorance about the clinical trial he is participating in is matched by his faith in his doctor. Marathe, who is undergoing a clinical trial on digestive disorders, is sure his doctor “will take care of him”.

The trial is being conducted by a well-known gastroenterologist in Mumbai. Marathe signed on a form in English, consenting to the trial. But ask him what it contains and he says with a smile, “It is a list of dos and don’ts for me to follow so that the doctor shouldn’t be blamed if something goes wrong. What those terms are, he isn’t too sure. In effect, Marathe is not really informed.”

This example quintessentially illustrates how the prerequisite of “informed consent” is arrived at in a clinical trial. It’s a safe bet that nobody will discover Marathe’s ignorance because the authority monitoring trials — in this case, an independent ethics committee — usually does not read the law to the doctor or investigator conducting the trial. The law requires the consent form to be printed in a language the participant understands, and signed by a witness if the participant is illiterate.

Says Dr Vimla Nadkarni of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences who has been on such ethics committees, “The danger with informed consent is that there is too much focus on the signed document rather than the process of the trial. The volunteers should be well-informed throughout the trial and not just while signing the form.”

A drug-controller officer adds, “Indian companies take short-cuts. Some simply tell us, ‘We have told the participants and that’s what matters. What’s the need for so much paperwork?’”

However, investigators claim that the issue of informed consent is a global problem. “It is present even in the US,’’ one investigator said. Like many other countries, there is also the problem of trials conducted by deception: A drug is recommended to a patient without his permission or knowledge to test its efficacy — for corroborating the company’s findings and not regulatory approval.

The lack of informed consent — or any consent — has always dogged clinical trials. But it assumes an urgency in view of the galloping international interest in outsourcing trials here. A large patient pool, cost efficacy and talent has made India a very attractive option for companies and other sponsors to conduct clinical trials. This is evident in the recent mushrooming of Contract Research Organisations (CROs), meant to conduct and deliver a trial for a party, in the country. “India today accounts for 1.3 per cent of global trials, up from 0.8 per cent last year,’’ says head of medical division, Pfizer, Dr Shoibal Mukerjee.

Experts voice the urgent need to clamp controls.

No inspections

Though a string of approvals including that of the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) and the local ethics committee are necessary to begin a trial, there is little monitoring once the trial gets underway. Arun Bhatt, president of a CRO ClinInvent, says, “Global companies are subject to a three-step vetting process: the investigator, the sponsor and the global auditor,’’ he observes. A senior DCGI official in Delhi told DNA that soon, all trials would be subjected to rigorous inspections.

Weak monitoring

There are two kinds of ethics committees: institutional and independent (which are not attached to any institutions). Conventionally, investigators are known to prefer the independent panels because they are considered more “tolerant” of minor issues. But all is not well with institutional committees either. In a public hospital in Mumbai, a purchase committee sometimes doubles up as the ethics committee. Worse, there is no monitoring of the committees either. “Some applications turn out to be marketing studies rather than clinical trials,’’ says Dr Urmila Thatte, who is on several ethics committees.

New law on the anvil

At the moment, the law applicable to clinical trials, is Schedule ‘Y’ of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940, which has been tightened last year to include one quality standard — good clinical practices (GCP).

Brijesh Regal, former WHO consultant to the drug controller of India, says the amendment brings Schedule Y on par with the global standards for conducting clinical trials. “We have, in fact, done better than most other countries on issues like ethics and informed consent by prescribing the precise language and processes for the purpose — to quell the feeling that our country’s population can be used as guinea pigs,’’ he said.

- Researchers at the Institute for Cytology and Preventive Oncology in New Delhi studied what happened to different stages of precancerous lesions of the cervix in 1,158 women — by leaving them untreated to see how many developed cancer. The women were not informed of what was done, or asked for consent. By the end of the study, 71 women developed malignancies. For nine, the lesions progressed to invasive cancer.

- A pair of US-based “barefoot researchers” led a massive, illegal multi-country trial of the potentially hazardous anti-malarial drug quinacrine as a terminal contraceptive — the drug was inserted into a woman’s uterus where it caused inflammation and literally burned and scarred the fallopian tubes to seal them off. More than 30,000 women in India were sterilised using this illegal and untested method, at least 10,000 in West Bengal alone.

- The government has been conducting trials of the injectable contraceptive Net-En in 12 medical colleges, as a prelude to introducing it in the family planning programme — though there has been materials suggesting that the drug has health risks and requires extensive screening that is not possible in a health system such as in India. The Centre started a publicity campaign in the press about how popular the injectable is with poor women.

- Dharmesh Vasava was among the many daily wage workers given a psychiatric drug as part of a bioequivalence study sponsored by the Mumbai-based Sun Pharmaceuticals. He developed pneumonia and died. The People’s Union of Civil Liberties suggested that the participants were unlikely to have been able to give voluntary informed consent to participate. The daily wagers were nomadic tribals. It was not possible to see what happened to the group.

- Mumbai-based Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Limited launched a programme by getting private doctors to prescribe the anti-cancer drug, Letrozole, to more than 400 women as a fertility drug for ovulation induction. They then publicised the doctors’ reports to other doctors as “research”. Off-label prescription of drugs was banned in India, prompting the Indian Medical Association to launch a campaign to permit off-label prescription.

![submenu-img]() ‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…

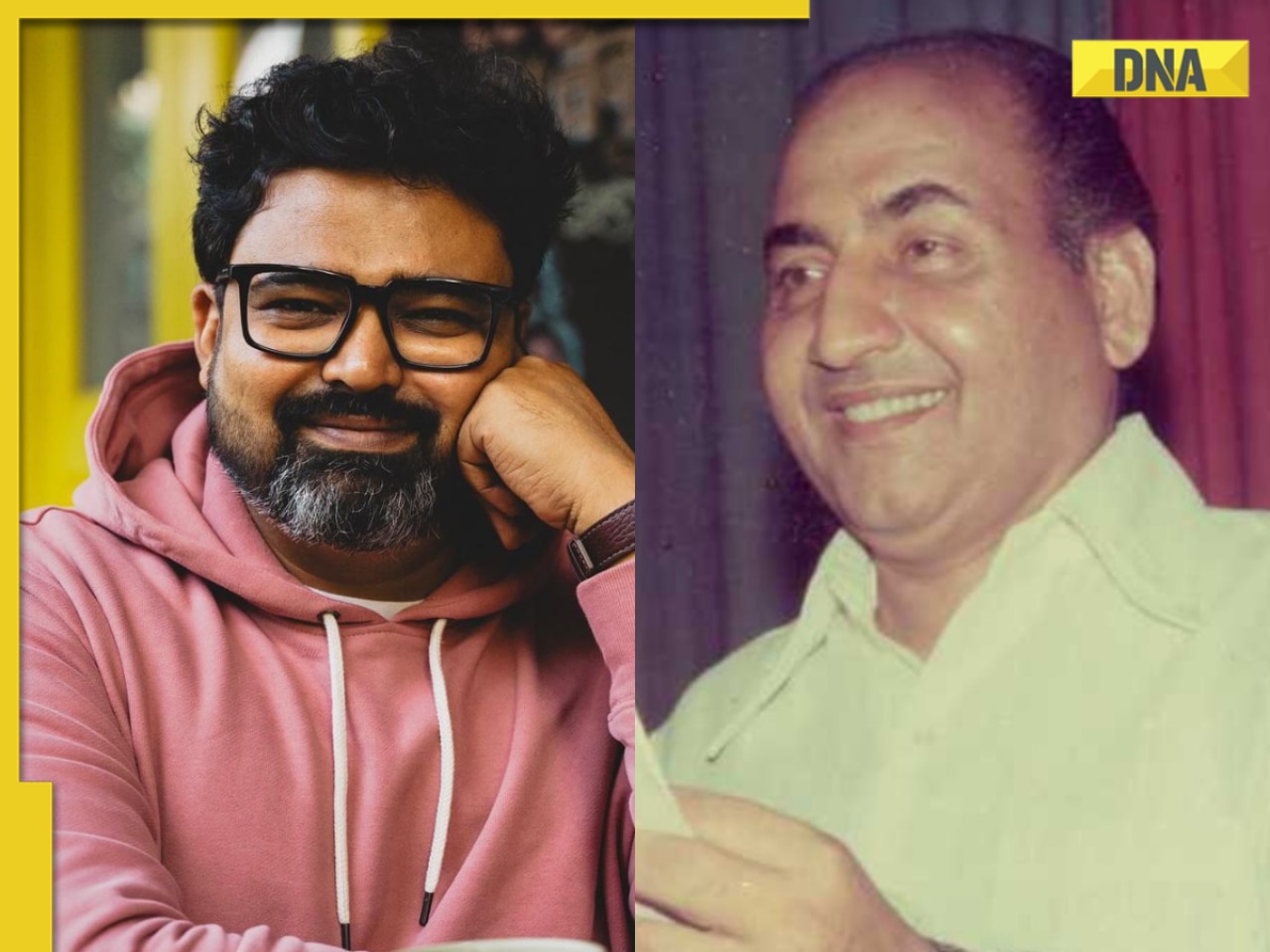

‘Paisa hi Paisa Hoga Ab’: Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani invites Pakistanis to UK estate, poses with ‘Bewafa’ singer…![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

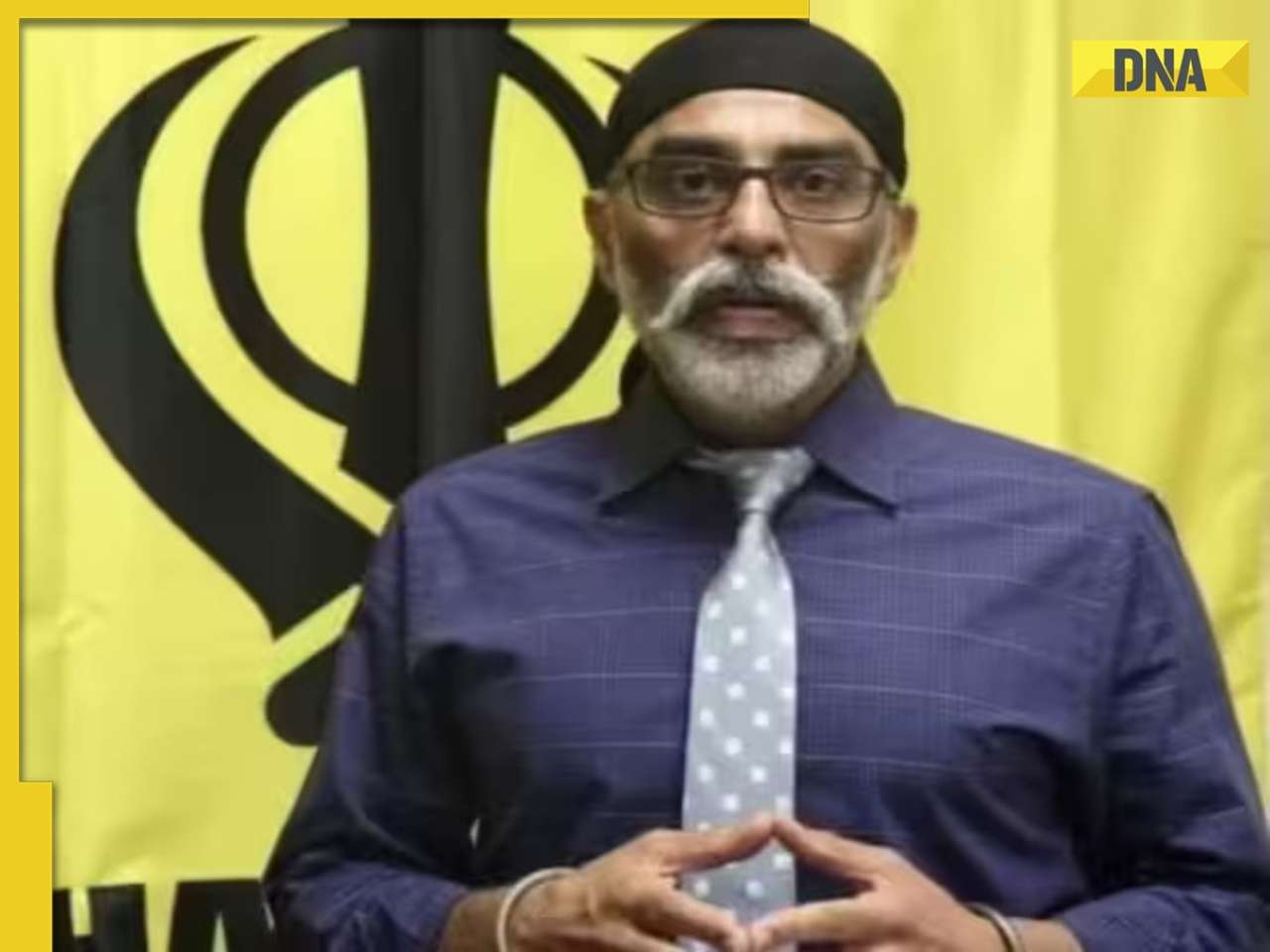

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() 'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot

'Unwarranted, unsubstantiated claims': India slams US media report on alleged Pannun murder plot![submenu-img]() JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy

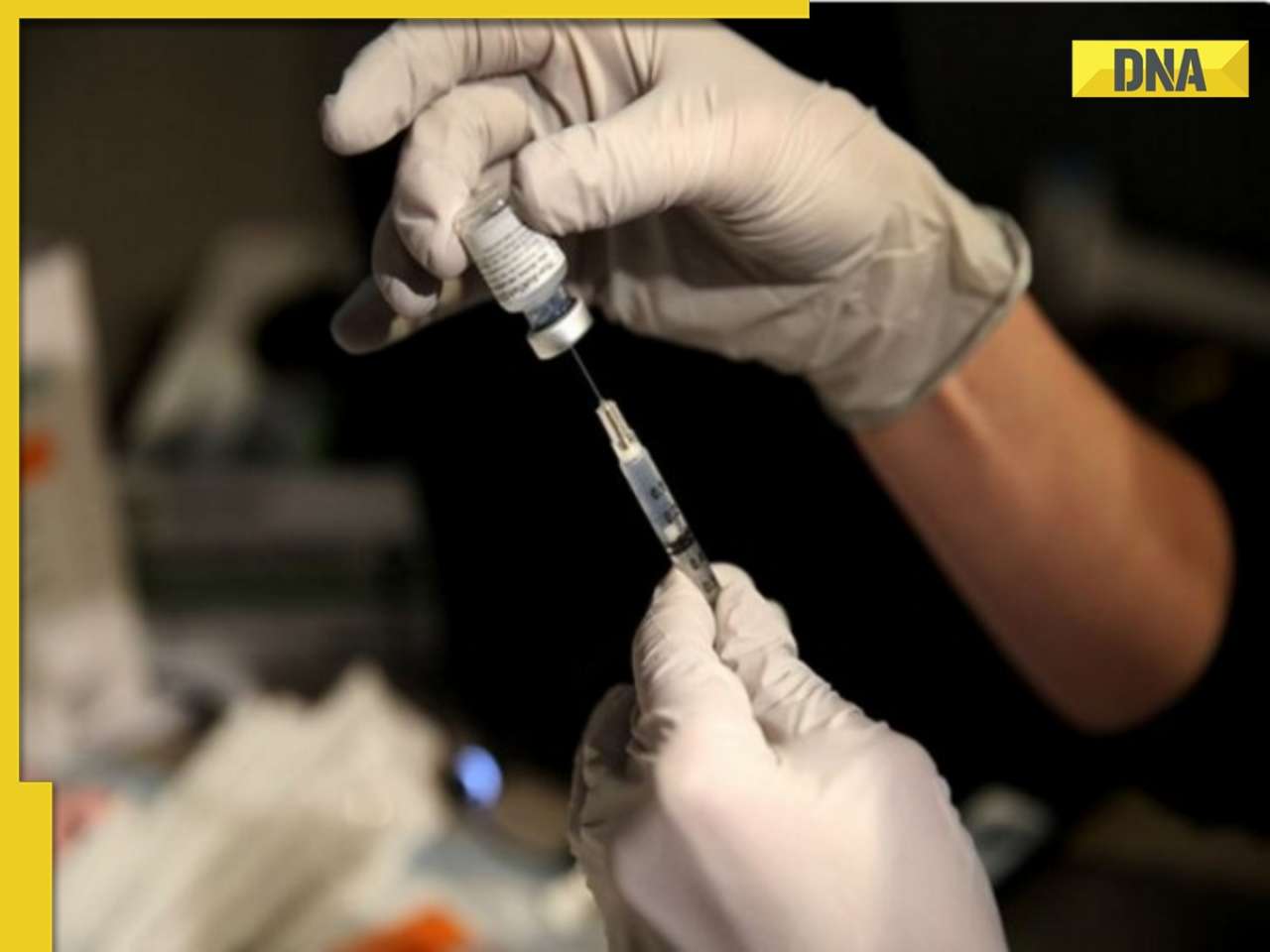

JD(s) to suspend NDA Hassan candidate Prajwal Revanna: Kumaraswamy![submenu-img]() AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...

AstraZeneca admits its COVID-19 vaccine Covishield can cause rare...![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive

Raj Shekhar reacts to AI-generated Mohammed Rafi version of 'Pehle Bhi Main': 'I sent it to my father' | Exclusive ![submenu-img]() Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’

Shekhar Suman slams young actors who ‘want stardom overnight’: ‘Why do they act…’![submenu-img]() Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..

Meet man who lived naked, alone, away from civilisation for 'cruel' reality show; remained in trauma for years, is now..![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore

Meet actor, who failed auditions, was thrown out of theatre, a curfew made him superstar; he’s now worth Rs 1800 crore![submenu-img]() Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...

Meet actor, who became star overnight, was called superhero of children, later quit acting; he now works as...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals

IPL 2024: Varun Chakaravarthy, Phil Salt power Kolkata Knight Riders to 7-wicket win over Delhi Capitals![submenu-img]() 'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket

'Won't find a place in my team': Virender Sehwag slams legendary India player for his comments on T20 cricket![submenu-img]() 'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024

'When people create imbalances....': Virat Kohli's sister reacts to RCB batter's strike rate chatter in IPL 2024![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

LSG vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians

LSG vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Lucknow Super Giants vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch

Viral Video: 4 girls get into ugly fight on Noida road, fly punches, pull hair; watch![submenu-img]() Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt

Private jets, pyramids and more: Indian-origin billionaire Ankur Jain marries ex-WWE star Erika Hammond in Egypt![submenu-img]() Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch

Viral video captures mama tiger and cubs' playful time in Ranthambore, watch![submenu-img]() Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch

Heartwarming video of cat napping among puppies goes viral, watch![submenu-img]() Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

Viral video: Man squeezes his body through tennis racquet, internet is stunned

)

)

)

)

)

)