Across the country, original work by young playwrights is making inroads into a scene long dominated by adaptations of established scripts, finds Apoorva Dutt

Playwright Ram Ganesh Kamatham remembers exactly when inspiration hit for his 2010 play, ‘Creeper’, an urban re-telling of the mythic story of Vikram and Betal. “It was October of last year,” recalls the Bangalore native. “I was on my way to rehearsal and got caught up in traffic. Then I realised it was caused by a fight that had broken out on Castle Street…a couple of south Indian guys were slugging it out with a couple of north Indian boys, and the only cop present had turned his back to them to diligently divert traffic.” The visual is one that would be instantly recognisable to any urban dweller, as would be Kamatham’s reaction: “I took the typical apathetic middle-class route — got the hell out of there,” says Kamatham.

Kamatham believes that this incident describes accurately what Bangalore is going through right now. “I tried to respond to this situation with the play, by placing a nostalgic 1980s Bangalorean voice against a rabid 21st century one.” The playwright hoped that this play would explore the futility of both positions, both of “retrogressive propaganda” and of glowing “development propaganda”.

Beyond adaptations

Kamatham is one of a growing breed of young playwrights around the country who are setting aside the time-honoured theatrical initiation of adapting established scripts, and instead, responding to their urban realities with original work. These young playwrights are nurtured by opportunities such as the Ranga Shankara festival in Bangalore, Prithvi theatre in Mumbai, and rented basements for readings and rehearsals in Delhi. They tackle topics such as road rage, widow remarriage, premarital sex and homosexuality. With increased opportunities and new scripts creating a stir in the theatre world, it is perhaps easier than ever before for budding writers to ‘break into’ the stage.

The winner of the recently concluded Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards (META) gave this development credence, when the coveted Best Play award went to ‘The Interview’, staged by the Mumbai-based Akvarious theatre group. The play, about a rookie’s job interview, dealt with what is perhaps the most primal urban instinct today — finding a good job, and what you’re willing to give up for it.

Mumbai-based playwright, Sidharth Kumar, got started in theatre by directing Damages by Steve Thompson and The Shape of Things by Neil LaBute. ‘The Interview’ was his first script, and the play has been running successfully in Mumbai theatres since December. Delhi-based playwright Neel Choudhuri, on the other hand, admits that getting funding and venues is a perennial difficulty. Courtesy of a grant from Max Meuller Bhavan, he is working on a new play, ‘Ich Bin Fassbinder’, about an Indian playwright who is obsessed with the German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder. “I am not interested in doing scripts which have no context or meaning in my world,” says Choudhuri. “Scripts on immigration and city life grab me like no Neil Simon play can.”

Renowned thespian Arundhati Nag was a jury member at the META ceremonies in Delhi last week. She noted that the scripts, while showing originality, were often “fragmented and episodic.” According to her, the younger playwrights don’t go in for conventional form anymore.

Responding to changing ethos

Rahul da Cunha, adman and theatre-person, is in agreement with Nag, and cites his latest play, ‘One On One’, a series of monologues, each of which has a different theme. “The monologue form is the theatrical equivalent of flipping channels,” says da Cunha. “The audience enjoys a different topic with each new monologue, and all of theme together talk about issues that the modern Indian will be concerned about.” Another Delhi-based playwright, Abhishek Majumdar’s monologue, ‘An Arrangement Of Shoes’, for instance, was described by critics as “rich visual interpretation”, and that it “does not come to us in the secure packaging of a conventional play.”

Even in the case of adaptations, the playwrights keep in mind the changing ethos of their audience. Majumdar began his career with an adaptation of Pratidwandi, a Bangla novel which explores the choices of a young man in Calcutta in the late 1960s, who resists the peer pressure to join the Naxalite movement. “The book focused on the political movement and the ideology, which I didn’t have access to. I changed it to a more personal narrative, into the story of a man who doesn’t want to follow popular trends.” Kamatham is also experienced with adaptations — his play ‘Snakes and Ladders’ was an adaptation of Doctor Faustus. “With adaptations, I try to focus on how the story can be in dialogue with the today’s realities. I reset the story of selling your soul as a tale of drug abuse — the devil was a drug pusher at a party selling ecstasy,” he says.

While venues like Ranga Shankara in Bangalore — where plays can be staged for a paltry sum of Rs3,500 a night — and Prithvi theatre in Mumbai, which offers subsidised rental rates of Rs5,000, encourage new talent, other problems have cropped up. “In Delhi, the National School of Drama (NSD) dominates the public imagination,” says Choudhuri.

Another issue is the informal nature of payment — theatre doesn’t exist in India as a formalised industry. As a result, there is no standardised payment for playwrights or directors. But some, like Majumdar, see the bright side to the organised chaos. “In the West, you have to go to an agent. Here, all you have to do is find friends who believe in you, make the play happen, and stage it. Alternative spaces, especially in Delhi where rental rates go upwards of Rs30,000, are a good option,” he says.

“I do think we should get adequate payment, but we can’t adopt the European system, which is culturally too different. In the developed West, theatre is an established institution; here it is more fluid, and I’m not sure that’s a bad thing. The creation of great plays is not something a society can take responsibility for. All we can do is make the stage available.”

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

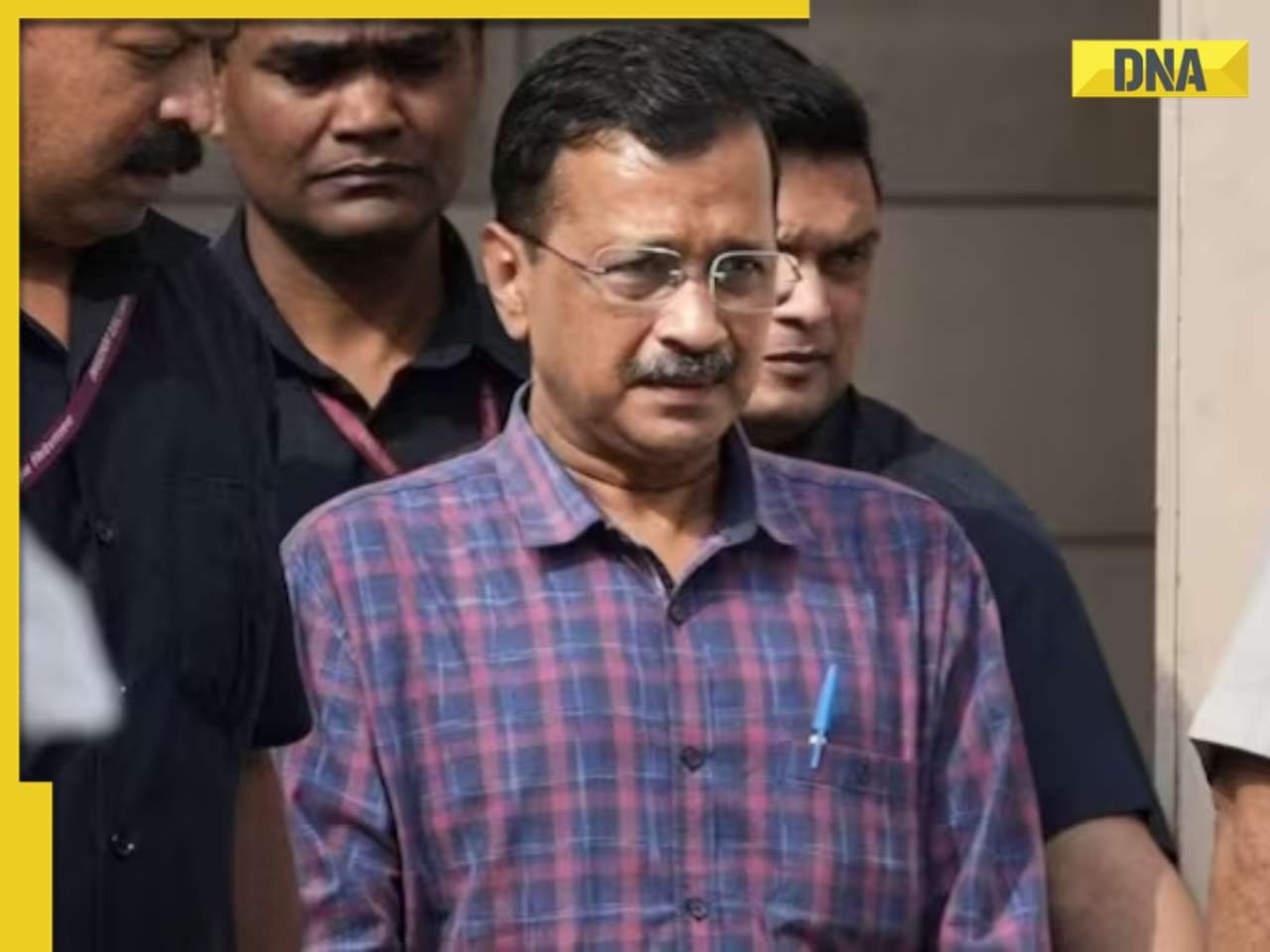

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

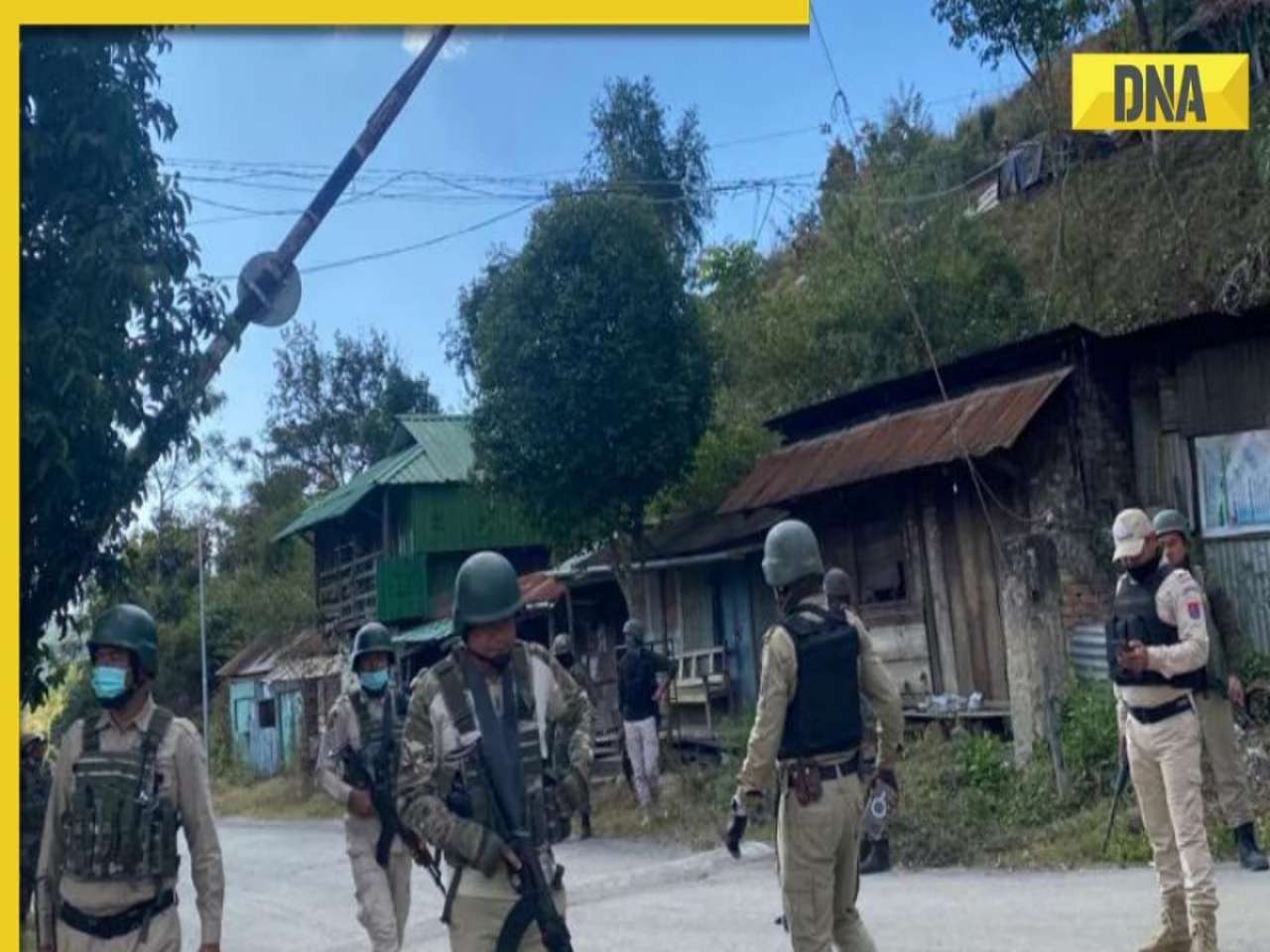

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)