South Indian filter coffee is the favourite hot beverage for many. But what goes into making the perfect cup of coffee?

What’s better than a piping hot cup of South Indian coffee? The answer: a cup of coffee that’s not quite ‘piping’ — that is, coffee that’s served between 80 to 90 degrees celsius.

This came as a bit of a shock to me. For the longest time, the drill for making coffee in my South Indian household had been the same: put powder in the filter, press the plunger over the powder, add boiling water, and wait for the coffee to percolate into the lower container. Next, boil the milk, mix it with the coffee decoction, heat it some more, air it to build up some foam, and serve. And in what has become a standard practice, the coffee would be sent back to be heated some more after dad had taken a sip or two.

And here I was, talking to experts who were telling me that the first mistake people make is expecting their coffee to be boiling hot. “You should be able to finish your Cappucino in 2-3 sips if required. That’s how hot your coffee should be,” said Gerson Aranha, CEO of Nilgiri Foods and Beverages, which supplies coffee beans to chains like Cafe Moshe’s and Mad Over Donuts.

“When you boil the water before pouring it into the filter, you are removing all the salts and the dissolved alkalinity. Water becomes flat,” says K Basavaraj, head of quality control at the Coffee Board of India. As I set about understanding the science behind South Indian filter coffee, I came to see that a range of compounds form the building blocks of the rich flavour and aroma that we enjoy. Brewing the perfect cup is really about extracting these compounds in the right proportions. My journey began with the beans.

Premium on peaberry

In South India, peaberry beans are considered a premium variety, unlike in Europe where it is considered somewhat inferior. Peaberry owes its fanatic fan following in India to its shape.

The coffee cherry (fruit) usually has two symmetrical oblong beans. As a result, the beans are flat on one side and rounded on the other. But sometimes one half develops more than the other. So, you get only one bean within the cherry, which is rounded all over. This is the peaberry and accounts for around 9-12% of the coffee crop.

“In the old days, when beans were roasted on a flat pan, the rounded beans would roast better than the ones which were flat on one side. Hence, peaberry beans yielded better coffee than the flat coffee beans,” says coffee coach Sahil Jatana, who conducts workshops on coffee brewing.

So why do the Europeans frown upon it? The proportion of soluble solids in a coffee bean, i.e., the parts which get dissolved in water, determines the strength of the beverage. A peaberry bean has around 20-22% soluble solids whereas a regular flat bean has 22-26%. The coffee turns out slightly stronger when made using flat beans.

The colour of the roast

Europeans also roast their beans to a darker shade to get stronger, more bitter coffee. Coffee beans start green, and are roasted up to varying degrees depending on the desired end result.

“The cellular structure of the bean absorbs the heat, becomes hard and expands. At roughly 217 degrees, all chemical structure is lost, and a series of compounds start developing. The sweeter compounds develop first followed by the bitter compounds,” says Basavaraj. A light roast such as Cinnamon Roast gives a wider range of flavours, a greater caffeine content, and better aroma, but the percentage of soluble solids is lesser. Hence the coffee won’t be too strong.

The City Roast is preferred for South Indian coffee. This is a medium roast, which provides a blend of flavour, aroma and strength, and yet not so bitter as to put off the Indian palate.

Gravitational pull

The roasted beans should be ground to a powder of medium consistency — too fine or too coarse is not ideal for the South Indian filter. The filter itself is a simple contraption comprising two containers. The upper container has perforations and fits on top of the collection container. A plunger in the upper container holds the coffee grounds in their place. The water should be heated to 90-95 degrees Celsius — turn the flame off when bubbles start appearing at the bottom of the vessel.

Basavaraj also recommends wetting the powder with a tablespoon or so of warm water before pouring in the hot water. “Coffee is a fibrous substance. The fibres expand when they get wet, and the extraction will be free flowing.” Because of the gravitational force, the water passes through the coffee powder and collects in the lower container. The light, volatile compounds get extracted first followed by the oils towards the end. Hence, filter should not be disturbed during the extraction.

Add hot milk and air the coffee by rapidly pouring it from one glass to another — this is best achieved using a dabarah. The oxygen in the air mixes with the coffee to release the volatile aromatic compounds.

Here my journey ended — my senses taking in the aroma of freshly made coffee, and its rich flavour. The difference was that I knew what exactly goes into the making of it, down to the last compound.

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

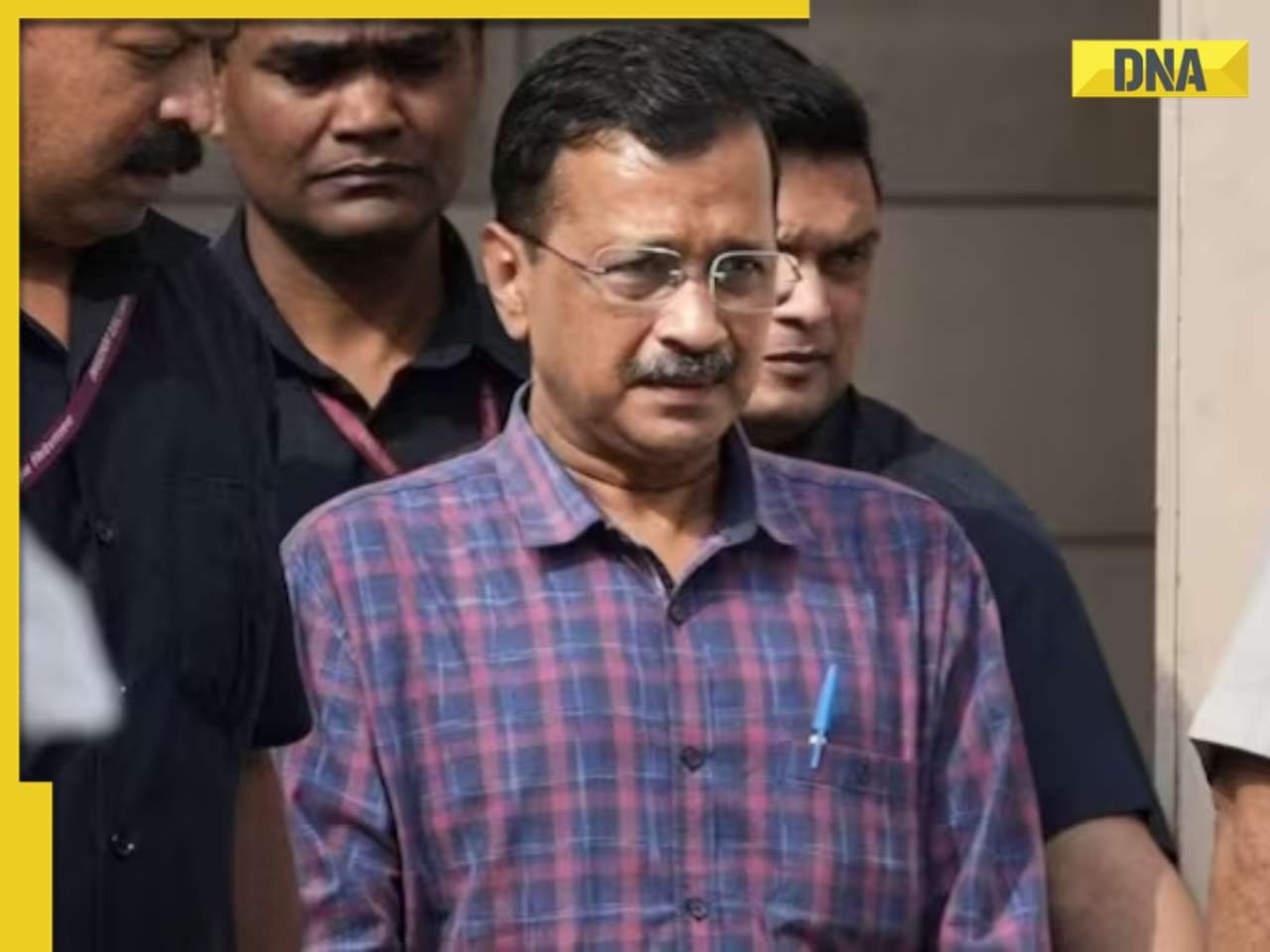

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

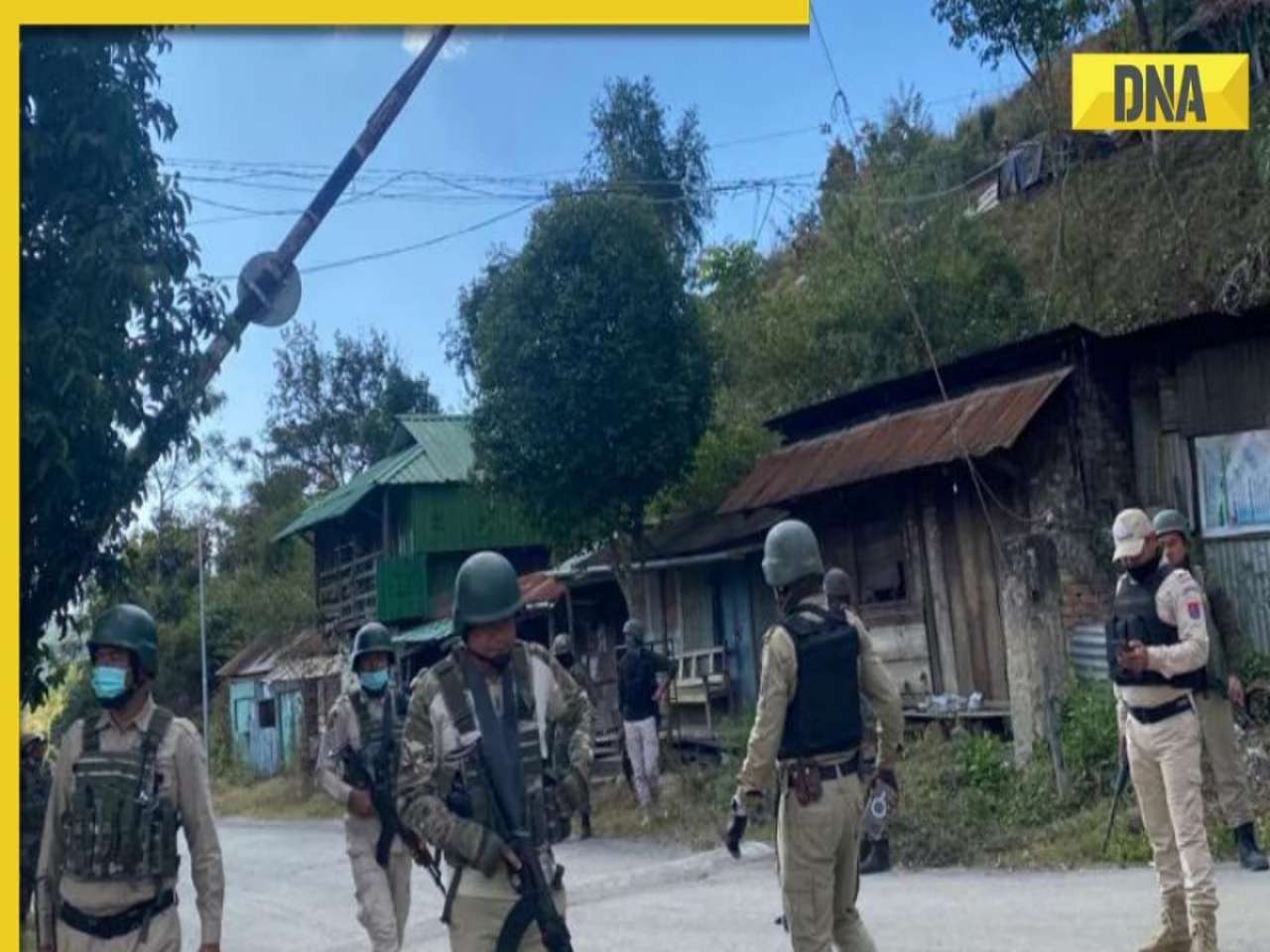

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

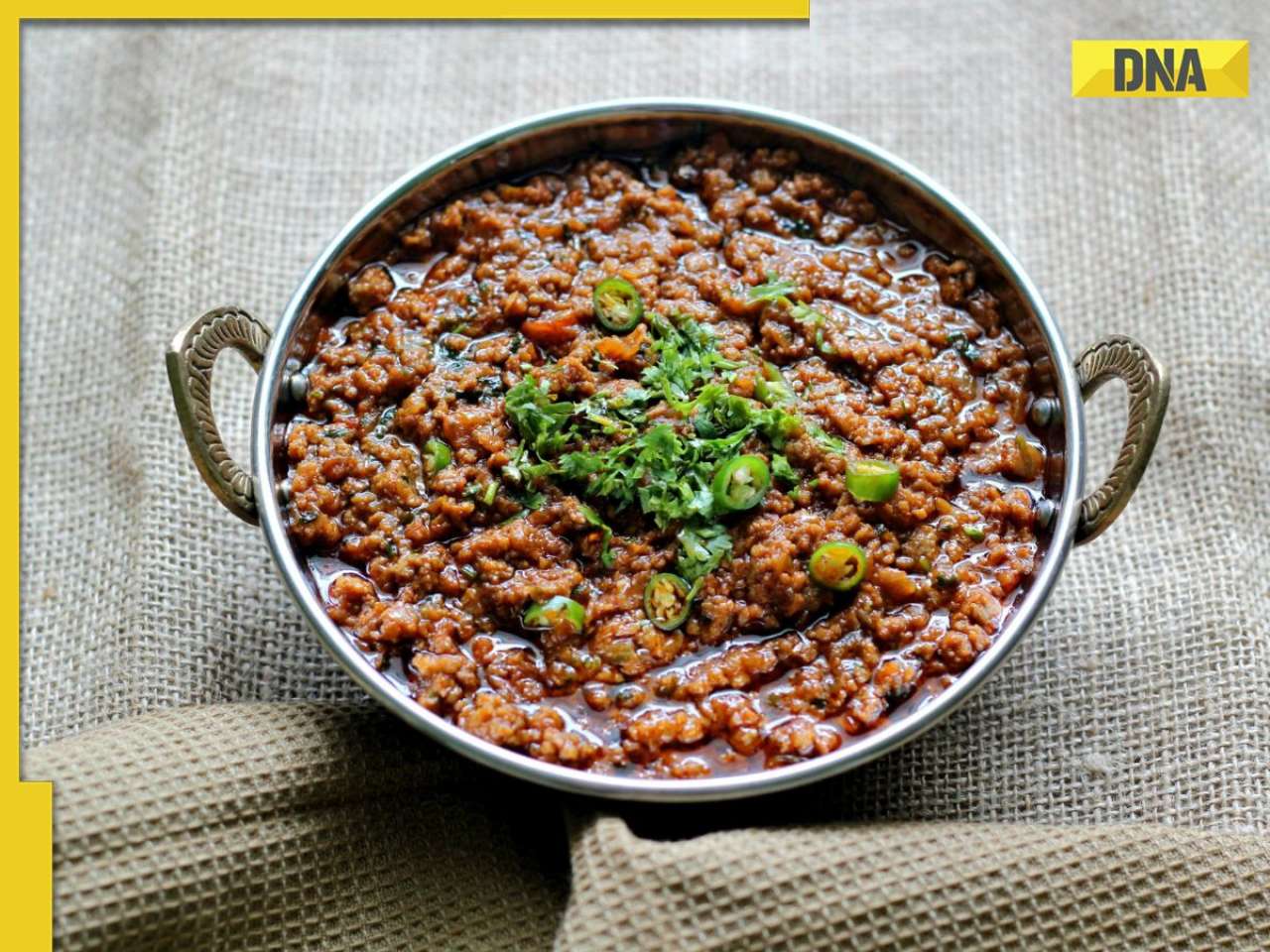

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

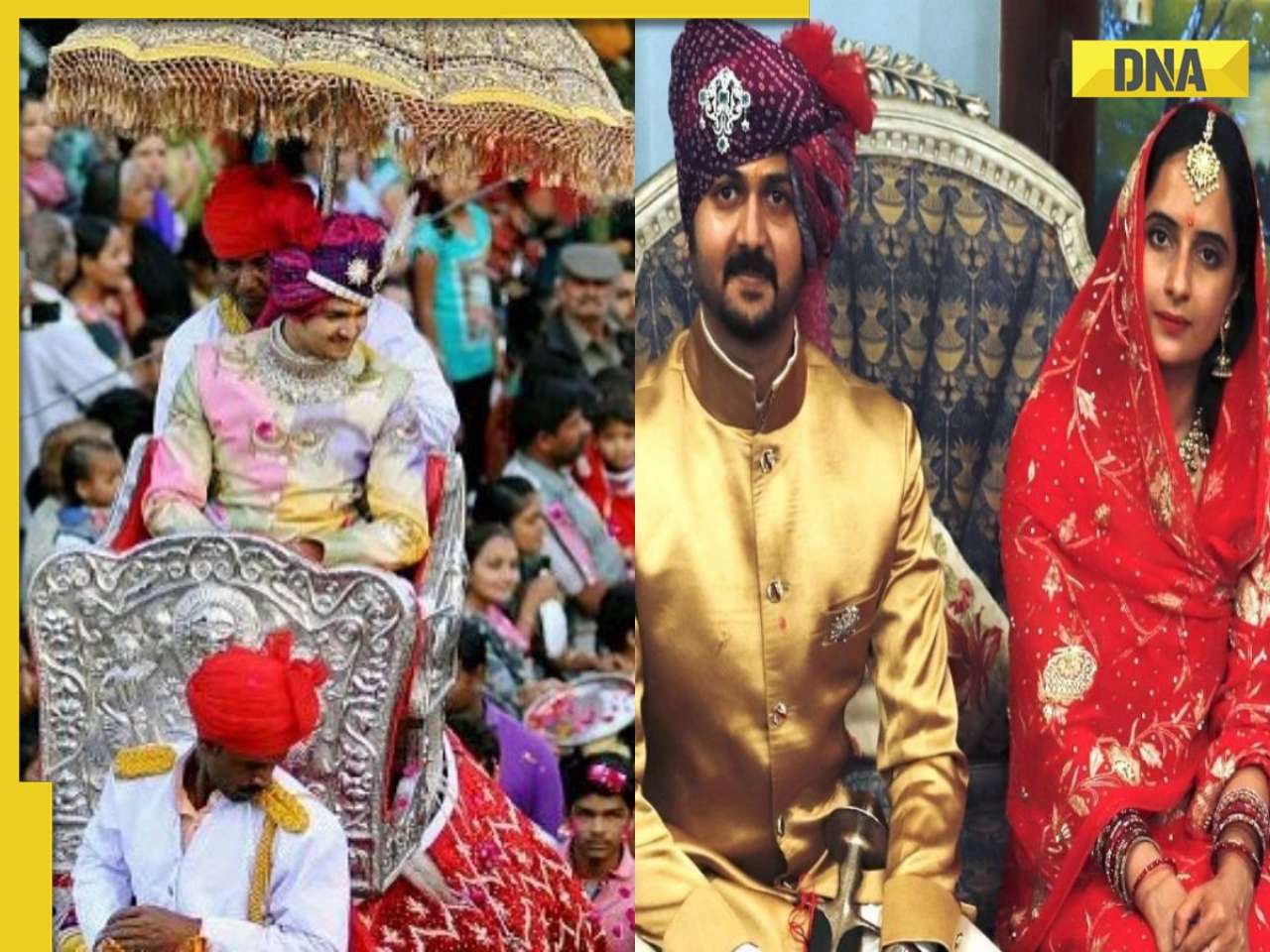

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)