Jairam Ramesh’s bold move to transfer forest management from district administration to Panchayati institutions destroys the autonomy of the joint forest management committees that have access to forestry funds.

Jairam Ramesh, India’s straight-shooting environment minister, has many good ideas and many more admirers. But his latest move to hand over forest management to the local community — aimed at giving a human face to those living in or near jungles — has alarmed even his closest supporters and allies.

The logic behind the move is simple — forest department officials often harass people who live off the forests collecting honey and other products, which leads to disaffection; so let local communities manage forests. As Jairam Ramesh puts it, “the Forest Department is only 100 years old. It is the British who established it to ease the commercial exploitation of forests and keep the locals out. We should get out of this mentality that a forest must be protected from those who live by it.”

Tribal rights activists have welcomed the move. “The management of forests should be handed over 100% to the (local) communities, and forest department officials should completely withdraw from the management committees,” says Bratindi Jena of the Adivasi Janajati Adhikar Manch, a tribal people’s movement active primarily in India’s eastern states like Jharkhand and Orissa.

“The tribals have been living in the forests for thousands of years without damaging it. They know how to take care of the forests better than the forest department. The forest department is the biggest zamindar in India,” she adds.

Jairam Ramesh has already written to all chief ministers to

ensure that the control of Joint Forest Management (JFM) committees — bodies that have access to the forests and the forestry funds — must be transferred to the local Panchayati Raj institution. In fact, “decentralised governance of forests” is the cornerstone of the Rs46,000 crore, ten-year Green Indian Mission that will be kicked off next year.

But there are many who fear that such an approach will destroy the local autonomy enjoyed by the JFM committees, considered India’s most successful forest protection and afforestation mechanism. Currently, JFM committees, comprising adult members from all village households, report only to the district administration and never to Panchayat functionaries. The Forest Department is kept involved too — a local forest guard acts as the member secretary of the JFM management committee, and keeps an eye on how funds are utilised, and whether encroachers are punished. Such autonomy is considered a key reason for the success of JFM committees in protecting and extending forests since the ’90s, even in areas where state forest departments had failed miserably.

Members of JFM committees fear that the changes will leave them powerless. “Right now, we don’t let anyone with an axe near the forests. But once we are submitted to the control of Panchayat politicans, we will be forced to turn a blind eye when their people cut trees or send in grazing animals to the forest… Not a single tree will be left in jungle,” says Mahaveer Prasad Sharma, a former Sarpanch and president of the JFM management committee at Kukadela village, Rajasthan.

According to Raghunath Sitaram Chowdhury, president of the JFM management committee at Ichchapur village in Burhanpur district, Madhya Pradesh, such schemes “framed in the air-conditioned rooms of Delhi” are destined to meet a quick death.

“Look at how National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme is being implemented. The sarpanch is making job cards in the name of his people and pocketing all the money himself. The problem is that [district government] officials go only by paper-work. If the papers are there, they don’t check on the ground,” says Chowdhury.

Chowdhury points to the several police cases filed against him and other JFM members by local Panchayat bigwigs. “When we stop their men from going into the forests, they file a case alleging that we beat them up. Now, we will be reporting to the same people,” he rues.

It is not just the autonomy of JFM Committees that is on the chopping board. According to the blue-print for the Green India Mission, the forest departments too will have to learn to live with a much smaller mandate. In a “decentralised forest management” paradigm, the forest department would act like a consultant to provide “demand-based” technical support to the Panchayat, according to Mission documents.

“NGOs now want to remove the forest guard from the committees,” points out AK Mukerji, former director general of forests, the highest ranking official in Government of India’s Forest Department. Mukerji, often consulted by Jairam Ramesh on forest-related issues, says he hopes to convince the minister to keep the ultimate responsibility for the forests’ well-being with the forest department, rather than the Panchayat. “One khakhi-wala (guard) has to be there in the committee to ensure order. You know how Panchayats function in India,” he notes, pointing out that forests do not belong to just the immediate community that uses it. “Its benefits go beyond the immediate community, and therefore, has to be protected as a national asset, not just a community asset,” he insists.

His words are echoed by Mudit Kumar Singh, principal conservator of forests for the state of Chhatisgarh, and who was instrumental in creating one of the earliest JFM models in Madhya Pradesh. “The forest is a scarce resource for which there is a lot of competition among the local community... If there is no forest department official, the interests of weaker individuals will not be protected and the powerful ones will take over. There will be a land-grab. It is like withdrawing the police.”

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

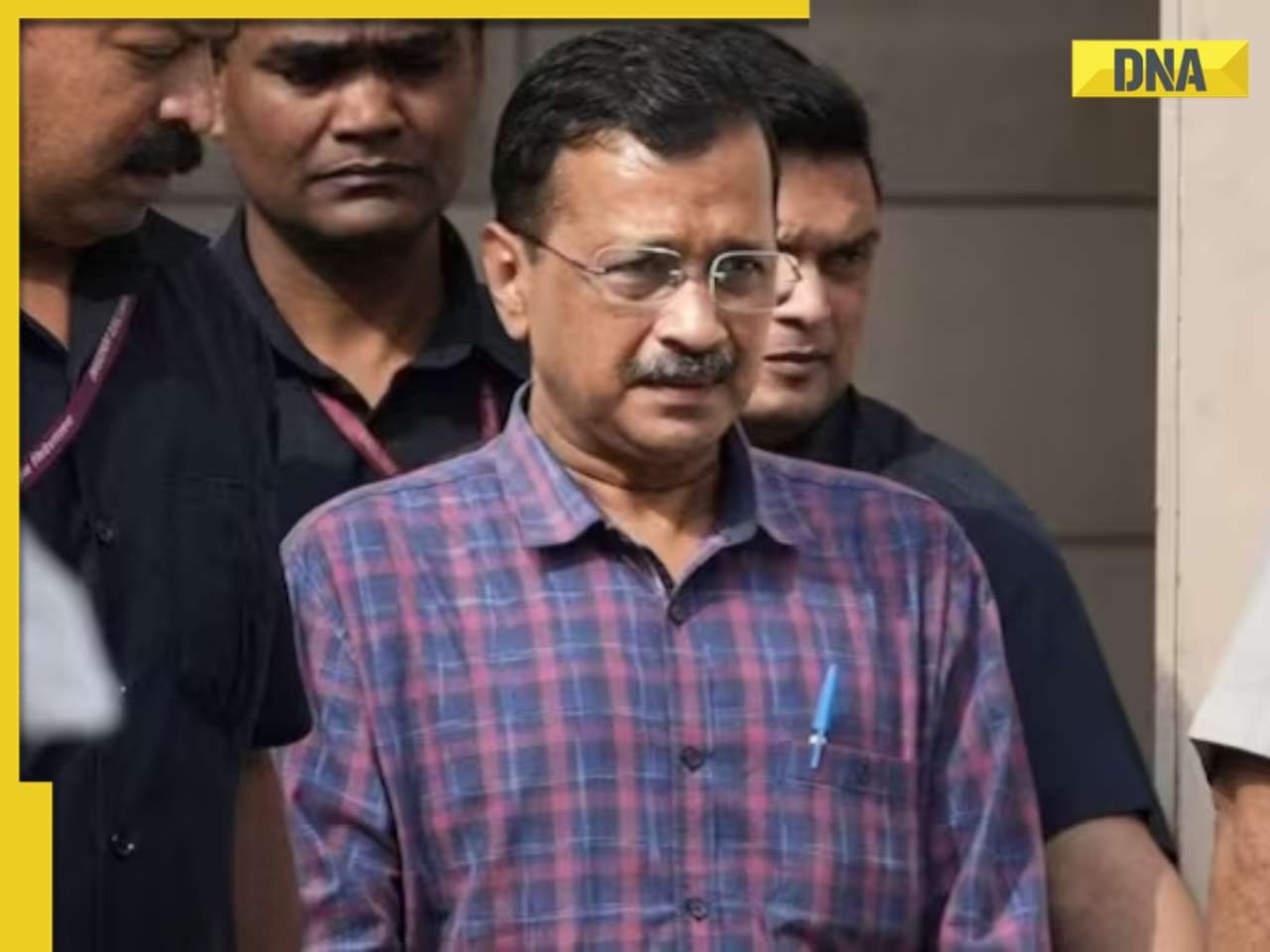

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

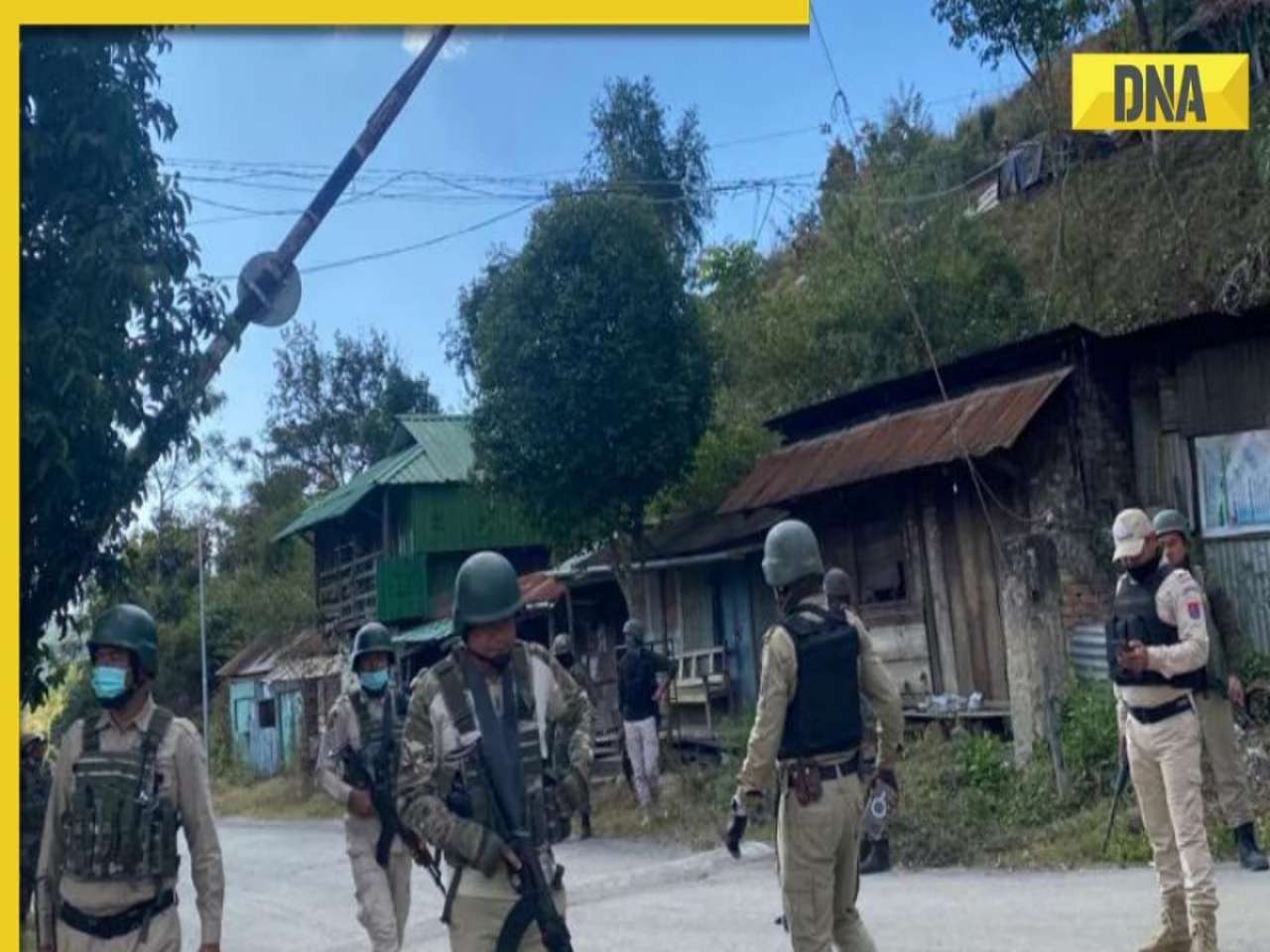

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)