The innocent em-dash — the line slicing a sentence into different parts — often comes under fire for being a sign of shoddy, lazy writing. But isn’t the em-dash a worthy inheritor of a long line of grammatical asides?

Like an inhibition-free starlet, the younger, flashier em-dash has left its older counterparts — the comma, colon and semi-colon — in the dust and risen to the top of the grammatical game. You can’t read a sentence these days without tripping over the author’s asides, footnotes, misgivings, jokes (ones too weak to hold an entire sentence together), concessions, second thoughts and prejudices.

This is partly, as author Lynn Truss in her book Eats, Shoots And Leaves noted, because: “The main reason people use the em-dash is that [they] know you can’t use it wrongly — which, for a punctuation mark, is an uncommon virtue.”

The em-dash, for grammar novices, is the longer version of the en-dash. It entered popular usage around the 1700s, and is called an em-dash because its length is considered to be equal to that of the letter m. And — while an en-dash enjoys pride of place on your keyboard — the em-dash requires some rather more complicated clicking maneuvers. As one colleague put it, it’s time for the em-dash to get an upgrade worthy of its stature: “Give it a raise, a corner office and a key of its own on the keyboard.”

And why not? The semi-colon is an antiquated relic; too formal and famously scoffed at by Kurt Vonnegut as “transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing… all they do is show you’ve been to college”. The comma is too half-hearted, the polite excuse-me of grammar, and the colon: a gracious gateway inviting you in, it is the neighbourhood aunty whose cookies smell and taste like they haven’t seen the inside of an oven since WWII.

The drunk of the gang

The em-dash, on the other hand, is the drunk of the gang. He is masculine, boisterous, and what he has to say stands out, demands recognition, and declares that the reader must pay attention or face the consequences. Bold and unsettling, it ushers parenthetical statements into a sentence with little regard for what came before or after. Consider it to be party-crasher — an immensely popular one.

Nandita Aggarwal, editorial director at Hachette publications, is all for the em-dash. “Long-winded sentences scare me, and they make all editors shudder. In contemporary writing, the style has become somewhat breathless. I’ll accept anything that adds a measure of coherence to writing. It shouldn’t be entirely disposed of — that would be throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater! — but taught as a good and versatile piece of punctuation.” Aggarwal hesitates and then bursts out: “I am very particular about grammar, but I kind of like these unconventional expressions. I like the smilie face. I’ve started putting smilie faces at the ends of rejection letters to would-be authors.”

Besides Emily Dickinson, a writer known for her unconventional use of em-dashes, it was the universally beloved Edgar Allen Poe who had risen to the em-dash’s defense: “Every writer…must be mortified and vexed at the distortion of his sentences by the printer’s general substitution of a semicolon, or a comma, for the dash... [this has] been brought about by the revulsion consequent upon its excessive employment about 20 years ago. The Byronic poets were all dash…”

Combing out em-dashes like lice

Author Anuja Chauhan seems to be opting for the em-dash as the lesser of evils. She says, “It’s way better than the semicolon, which I loath. It makes me feel like I’m reading the Indian Constitution. The em-dash is more natural, and closely mirrors “the way people speak. It gives a cozy, chatty feel.”

But others are not as enthusiastic. Author Ann Patchett claims to have lived a childhood entirely devoid of em-dashes, thanks to holy intervention. “I grew up in a Catholic school, and I’m sure the nuns who taught me had never seen an em-dash. What I did not know I did not miss.” Oddly enough, Patchett’s relationship with the em-dash began where most authors’ ends — at the editing stage. “Copy editors kept putting them in my books, and they just keep increasing with time. I patiently comb them out like lice, leaving just a few in to make myself look modern.”

Is the em-dash just the newest attempt to reinvent the wheel — and will it be followed by yet another grammatical player taking over in a hundred years or so? Perhaps it will be the renaissance of the Interrobang — the fusion of a question mark and exclamation — which will captivate writers and editors alike?

Conceptualised by an advertising agency in the ’60s, the Interrobang is simultaneously efficient, attention-grabbing, contemporary, and fun to say. Writer Shinie Antony, while not commenting on the innovative brilliance of the Interrobang, agrees that the em-dash might just be the flavour of the century. “The ellipsis was replaced by the semicolon. Then everyone started complaining that the semicolon was overused and the em-dash came to the rescue,” she explains.

Antony points out, with a generous helping of common sense, that “punctuation puritans” should just focus on whether the sentence makes sense or not, and rest the matter there.

But what’s the theory-based fun in that? As far as we’re concerned — and that is a great amount of concern — the em-dash versus the comma/colon/semicolon war is likely to rage on — unconcerned with breathless readers — but only till the interrobang makes its entrance into the mainstream. Won’t the em-dash era end with a bang?!

![submenu-img]() Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'

Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'![submenu-img]() Weather updates: IMD issues severe heatwave condition in these states; check forecast here

Weather updates: IMD issues severe heatwave condition in these states; check forecast here![submenu-img]() Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case

Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case![submenu-img]() Bank Holidays in May 2024: Branches to remain closed for 10 days this month, check full list

Bank Holidays in May 2024: Branches to remain closed for 10 days this month, check full list![submenu-img]() Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'

Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'

Remember Heyy Babyy's cute 'Angel' Juanna Sanghvi? 20 year-old looks unrecognisable now, fans say 'her comeback will...'![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'

Sonam Kapoor says she gained 32 kg during pregnancy, was traumatised: 'Never going to feel the same'![submenu-img]() Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case

Sahil Khan detained by Mumbai SIT in Mahadev betting app case![submenu-img]() Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'

Govinda had tears in his eyes on seeing Arti Singh as bride, Krushna Abhishek reveals: 'Agar woh thodi der...'![submenu-img]() Aamir Khan recalls ex-wife Reena Dutta slapping him when she was in labour: 'She even bit my hand'

Aamir Khan recalls ex-wife Reena Dutta slapping him when she was in labour: 'She even bit my hand'![submenu-img]() Britney Spears settles legal dispute with estranged father Jamie Spears over conservatorship, details inside

Britney Spears settles legal dispute with estranged father Jamie Spears over conservatorship, details inside![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Sanju Samson, Dhruv Jurel fifties help Rajasthan Royals take down LSG by 7 wickets in Lucknow

IPL 2024: Sanju Samson, Dhruv Jurel fifties help Rajasthan Royals take down LSG by 7 wickets in Lucknow![submenu-img]() IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Mumbai Indians by 10 runs

IPL 2024 Points table, Orange and Purple Cap list after Delhi Capitals beat Mumbai Indians by 10 runs![submenu-img]() CSK vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

CSK vs SRH, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Rasikh Dar power DC to 10-run win over MI

IPL 2024: Jake Fraser-McGurk, Rasikh Dar power DC to 10-run win over MI![submenu-img]() 'If I don’t get a chance despite...': Shubman Gill makes big statement ahead of T20 World Cup 2024

'If I don’t get a chance despite...': Shubman Gill makes big statement ahead of T20 World Cup 2024![submenu-img]() Viral video: Rediscover childhood bliss with this nostalgic 90s birthday party plate, watch

Viral video: Rediscover childhood bliss with this nostalgic 90s birthday party plate, watch![submenu-img]() Ever seen elephant playing cricket? This viral video will leave you stunned

Ever seen elephant playing cricket? This viral video will leave you stunned![submenu-img]() Mukesh Ambani lost 15 kgs without any workout, his secret diet plan includes...

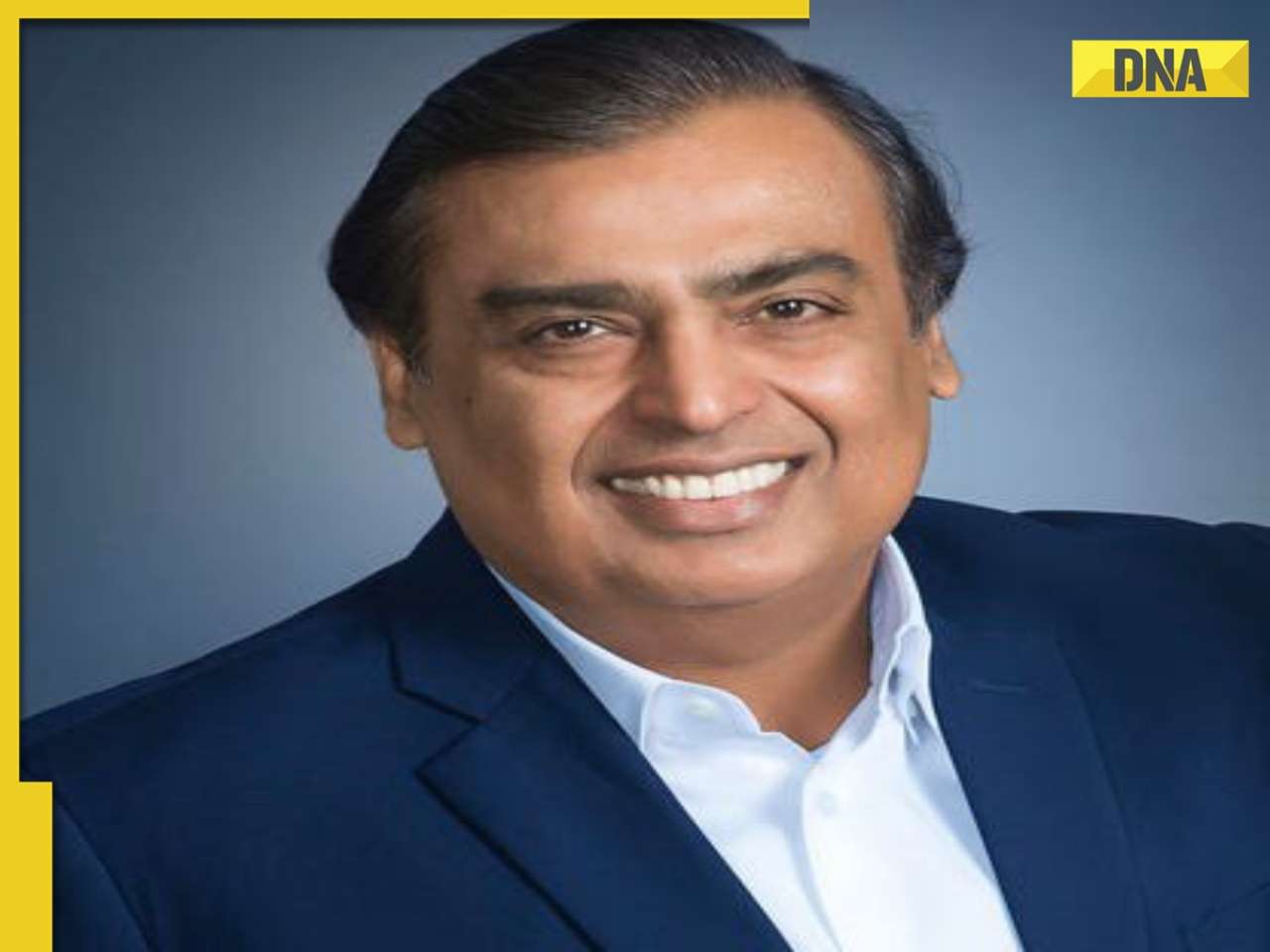

Mukesh Ambani lost 15 kgs without any workout, his secret diet plan includes...![submenu-img]() Viral video: Groom's daring leap during varmala ceremony leaves internet in stitches, watch

Viral video: Groom's daring leap during varmala ceremony leaves internet in stitches, watch![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

)

)

)

)

)

)