The award-winning Filipino director tells Malavika Velayanikal how he went in search of his tribal roots, and found his inspiration for cinema.

A collective gasp rose from the audience at the Bengaluru International Film Festival as they watched slimy worms crawl out of Punay — the protagonist in Busong. They sighed as the worms wriggled out wings and became beautiful butterflies.

Gasps and sighs don’t surprise its director Auraeus Solito. He has seen viewers respond this way since Busong first screened at the Cannes festival last year as the official selection for Directors’ Fortnight. “That Busong moves far-off audiences is heartening,” Solito tells me, raising his hand to his heart and bowing.

Busong (Fate) is the second part of Solito’s trilogy on Palawan, his tribe in the Philippines, a dream project that had been incubating for 15 years while he established himself as a filmmaker. His films now tell the stories he feels are vital to a world that is fast losing touch with nature.

Busong explores the Palawan concept of fate. “It’s like instant karma. When you do something bad to nature or your fellow men, it strikes back at you instantly,” explains Solito.

The beginning

The story of how Auraeus Solito became a filmmaker begins when he was just a little boy in Manila, hankering after stories. His mother told him strange, magical tales of a faraway land, where man and nature were a seamless being. He heard her speak in a mysterious language when her relatives visited. To little Solito, it sounded like “bird tongue”, the language of birds. He smelt a secret — one which took twenty years to unravel. “In Manila, people often mistook me for a foreigner.” His physical features — hair, face, limbs — were distinct. “Look at my hands,” he says.

“They are Palawan.” It was only while majoring in theatre art at the University of Philippines that he learned he belonged to a tribe called Palawan, but there was hardly any information about them. His mother had taken him to the Palawan islands once as a toddler. Images from that trip of mountains, lakes, flying squirrels and mud-skippers stayed with him. For his final year thesis in college, Solito wrote a script interweaving those memories and his mother’s stories. “The professor who read it told me: ‘Go back to where these stories came from. Nobody knows these. Go back to your roots and that’s where you will find your calling’. And I went.”

Finding himself

The boat journey to the Palawan islands was “like a doorway to another world”. Solito heard for the first time that he was a descendant of the Shaman kings of Palawan. “I was discovering paradise, the land of my dreams and memory.” He underwent shamanistic training with his uncle for two years. He mastered Taruk, their dance. “The music of the drums is the key. You have to follow the rhythm with your feet, hands and body, and you dance with your eyes closed. At one point, the music will take over your brain, and you get into a trance.” He learnt the Palawan language and their tribal spells, even bettering his cousins in some of them.

For seven years, he lived there, soaking in every aspect of his tribe.

His mother’s family had converted to Christianity when missionaries first came to parts of Palawan. Soon, fissures began to appear. “It became “they” and “us” — something that never existed earlier when the tribe shared every resource, food, water, everything,” says Solito.

His mother later moved out to Manila when she won a scholarship to study law. “There she met my father, married him, and had me — the first Palawan to be born outside of our tribal land. She hid her Palawan roots from me because she was ashamed of them.”

Palawan was mostly insulated from the Spanish colonisation because of the tough terrain. “The mosquitoes saved Palawan,” quips Solito, explaining how the place retained its beauty. “Over the last decade though, our fellow Filipinos are colonising Palawan. Beautiful sandbars around our islands have been taken over by rich businessmen for pearl farms. Its rich deposit of minerals and precious metals has attracted a number of mining companies that have begun large-scale strip mining operations.

Trees are being cut indiscriminately, and gun-toting guards are everywhere. The natives cannot go near their sacred sandbars anymore.” Solito joined environmentalists and activists to fight these encroachments, and they moved court. Soon, he began to receive death threats. “Finally, I was forced to head back to the city as everyone urged me to do so.”

Moving to cinema

Solito returned to Manila determined to tell the stories of Palawan. “The world should hear about the ancient culture of Palawan, their knowledge and wisdom, and their absolute harmony with nature. These stories mustn’t die.”

Solito wanted a canvas larger than theatre to do this. He needed cinema. So he attended a summer workshop at the Mowelfund Film Institute on basic filmmaking. But it was impossible to find funding for a film on the tribe. Then he decided to go the mainstream way to gain recognition. In 2005, he made Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros (The Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros), a $10,000 film about a 12-year-old gay in Manila. It was the first Filipino feature film to score big in the West. It won 15 international prizes, including three at the Berlinale. His next film Tuli (Circumcision) was about a villager who fights the tradition of circumcision. Then he made Pisay (Philippine Science) about six teenagers in a science school discovering themselves. His fourth film Boy (2009) was the story of a poet who sells his collection of comic books and action figures to hire a male stripper on New Year’s Eve. All four films bagged awards and had the box-office ringing.

In 2010, Solito was chosen for a screenplay development programme at the Binger Film Lab in Amsterdam. There, he wrote Delubyo (Deluge), the first part of his Palawan trilogy. But it was the second part, Busong, which got funding because it was cheaper.

Solito had planned to cast Dr Gerry Ortega in Busong. Ortega was a leading environmentalist who was fighting the mining industry in Palawan. The day before shooting began, Ortega was murdered.

He was shot in the head from behind. “We were up against dangerous enemies. But we finished shooting in 20 days,” says Solito.

On January 24, the first death anniversary of Dr Ortega, Busong will screen in Palawan. And Solito has also started work on Delubyo.

The learning

Apart from becoming the inspiration for his films, Solito’s search for his roots even gave him a new name, rather his “real” name — Kanakan Balintagos, meaning the hunter of truth. “This is my tribal-spirit name. My uncle dreamt it when I was born,” he says.

Solito now feels at ease anywhere in the world; the disconnect he felt while growing up has vanished. “I am like a Kukok — a shape-shifter, who can change his appearance to suit situations,” he laughs. A lone Brahminy Kite circled far above our heads as he was talking. “It is a Palawan omen,” Solito smiles.

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

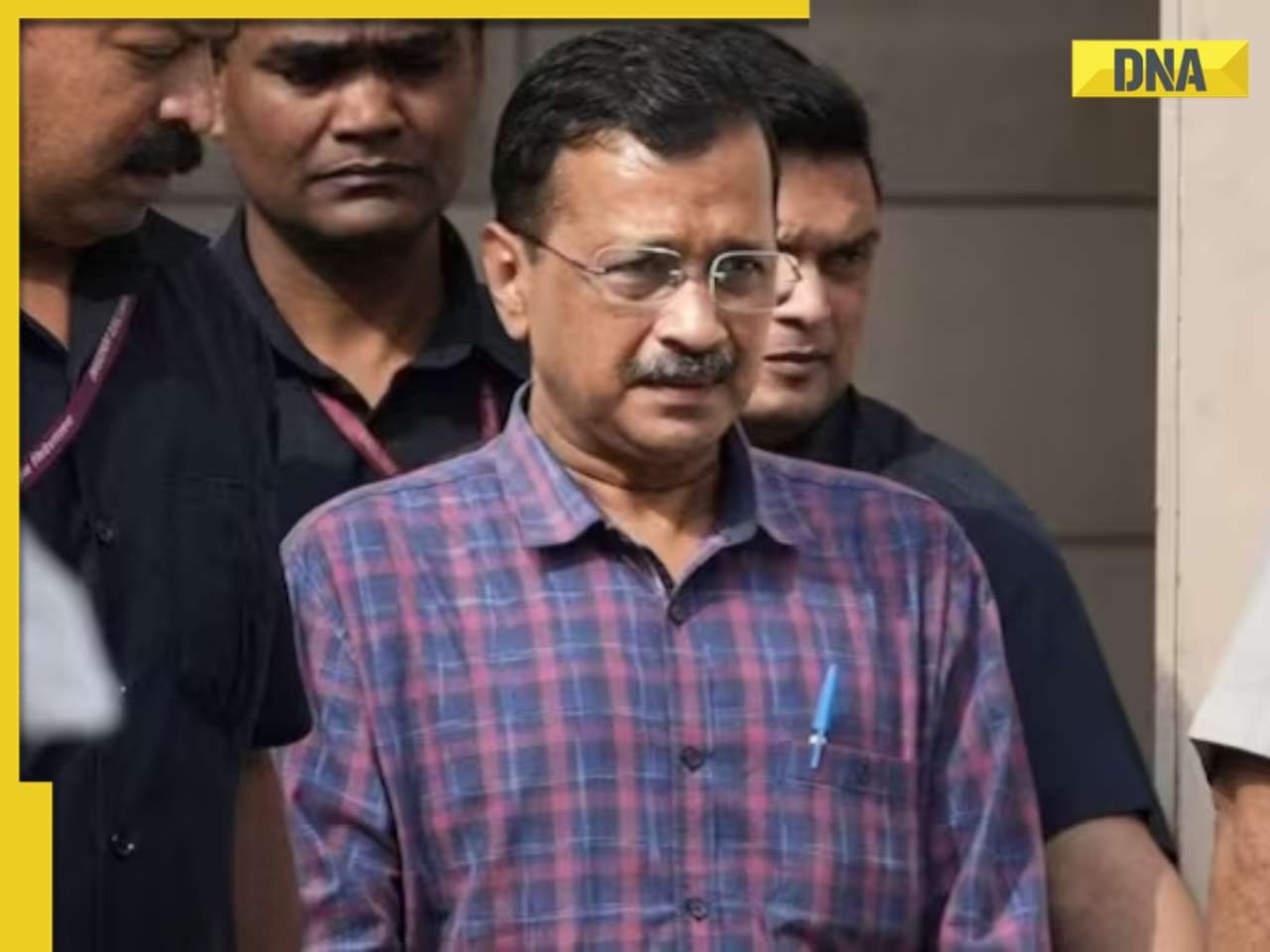

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

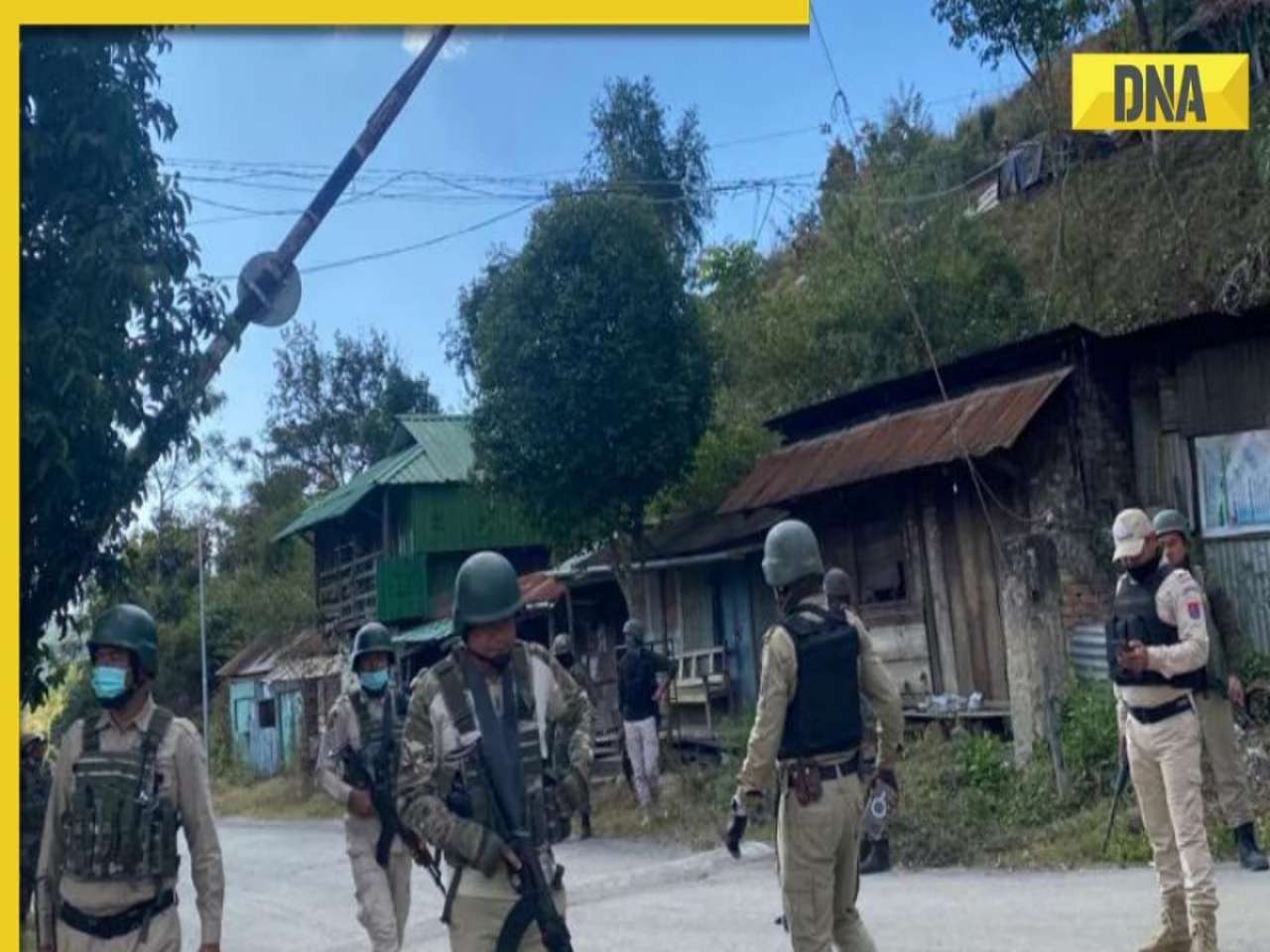

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)