Lt. Cdr. Abhilash Tomy, a reconnaissance pilot with the Navy and the first Indian to navigate the globe solo and non-stop, talks about how meditation aided him in solitude and how it has changed is outlook towards life

The experience of solitude has had a life changing effect on me. My first solo boat trip was in 2011 from Cape Town to Goa. The voyage did not begin well because in the first week itself I lost a batten, the sail tore, the generator caught fire, the mechanical autopilot broke and the electronic autopilots stopped holding course because the wind instrument had stopped working right. All this while I was suffering from seasickness. There was a gale blowing outside, but from my experience the immediate threat came from within–an unsettled mind. I didn't know much about meditation then, but I knew that repeating a sound calms the mind, so that's what I did. Consequently, the remaining voyage was a blissful experience and I began to enjoy the solitude. In fact, when I stepped on land for the first time after a little over a month, the transformative effect of the journey was already showing–I turned vegetarian even though meals at the Catholic household I grew up in are incomplete without meat, fowl or fish. In the following months, I found someone to teach me meditation techniques to practise on a daily basis.

From June 2011 to October 2012 I was preparing the boat for another long voyage; I was challenging myself, with the help of the navy, to sail around the world non-stop and solo. I was preparing myself for almost six months of extremely stressful conditions, and the boat, for taking severe beating day after day. Tales of seafarers are rife with stories of sailors committing suicide on such ventures. On November 2012, I was finally set to sail.

During the voyage, I would partake the first meal only after meditation, no matter what weather we sailed in or what pressing emergency stood my way. There was though, a patch in the Pacific where I stopped meditating; it affected the way I took rest and my mental well-being began to ebb. Recognising the symptoms, I restarted. By the time I had rounded the most feared cape, Cape Horn, I had spent 86 solitary days at sea soaking up a heady concoction of bliss and detachment that came with solitude and meditation. That day, when I saw land for the first time in almost three months, I was depressed that the voyage would end someday.

As the voyage progressed and difficulties increased, I found that meditation was helping me understand the mind differently; I realised the mind itself can be seen as an entity other than the self because of which it can be easily controlled. I became so good at controlling my mind that when disaster struck, I discovered uncoloured ways of solving problems rather than responding emotionally. One particular incident that I vividly recollect pertains to a line that parted on top of the mast. It was the 10th of January and I was in the middle of the Pacific. The sea was about 3 metres and in an instant I had realised that I would be living through one of the most difficult days of my life, because in the next couple of hours I would have to climb a mast that was as tall as a seven storey building (and it was swaying quite a lot thanks to the sea), fix the parted line and come down. Instead of cursing the day or my decision to embark on something like this, I prepared myself to climb, completed the task at hand and came down.

Because of meditations I was also in tune with everything around me. There were many instances where I could sense things before they happened. Sometimes I would dream the exact same dreams as some of my friends on land, or be able to tell that something important had happened back home just by what was happening in the boat.

Living away from human society also altered many notions that I had been indoctrinated with since childhood. Life existed at an essential level as I survived with limited resources in a hostile environment. The self, though, was active, introspective and asking questions, which I hadn't had the time to answer earlier. My concepts of right and wrong, good and bad, real and unreal, guilt and even God were transforming. By the end of the voyage I was sure that what I saw in the material world was actually immaterial in my pursuit of happiness. Not having conversations with anyone also meant that I didn't have to convince anyone. I stopped lying, exaggerating or inventing stories except for the occasional blogpost and interactions with the world still bound by land. The sea itself taught me a lot with its passionate yet impersonal style that barely acknowledged my existence. It would be calm now and very rough the next moment. In the beginning I only noticed its playfulness, but in time I saw the unseen depths of the sea, where it was always calm, unchanged. The sea was the cause of my troubles, but I knew that it was also the cause of my heroics. It threw troubles my way, never wanting to know what I was, who I was, what I thought or what ingenious excuses I could come up with–only what I could do and how.

I had to return to the starting point of my voyage to know how much I had changed. I still saw people chasing the same physical comforts and trying to alter their external conditions to suit their needs and find happiness. When it poured, I saw them opening umbrellas in defense without realising that what they experienced as rain was possibly not rain, but a recreation of the mind.

Over a year since I've returned to land, I now look at the world differently. I have realised that all that you see, touch and feel may not necessarily be reality. My life has become more spartan–at home, I neither use a fan nor an air conditioner even in the worst heat, and I definitely feel like I am a part of a greater whole.

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

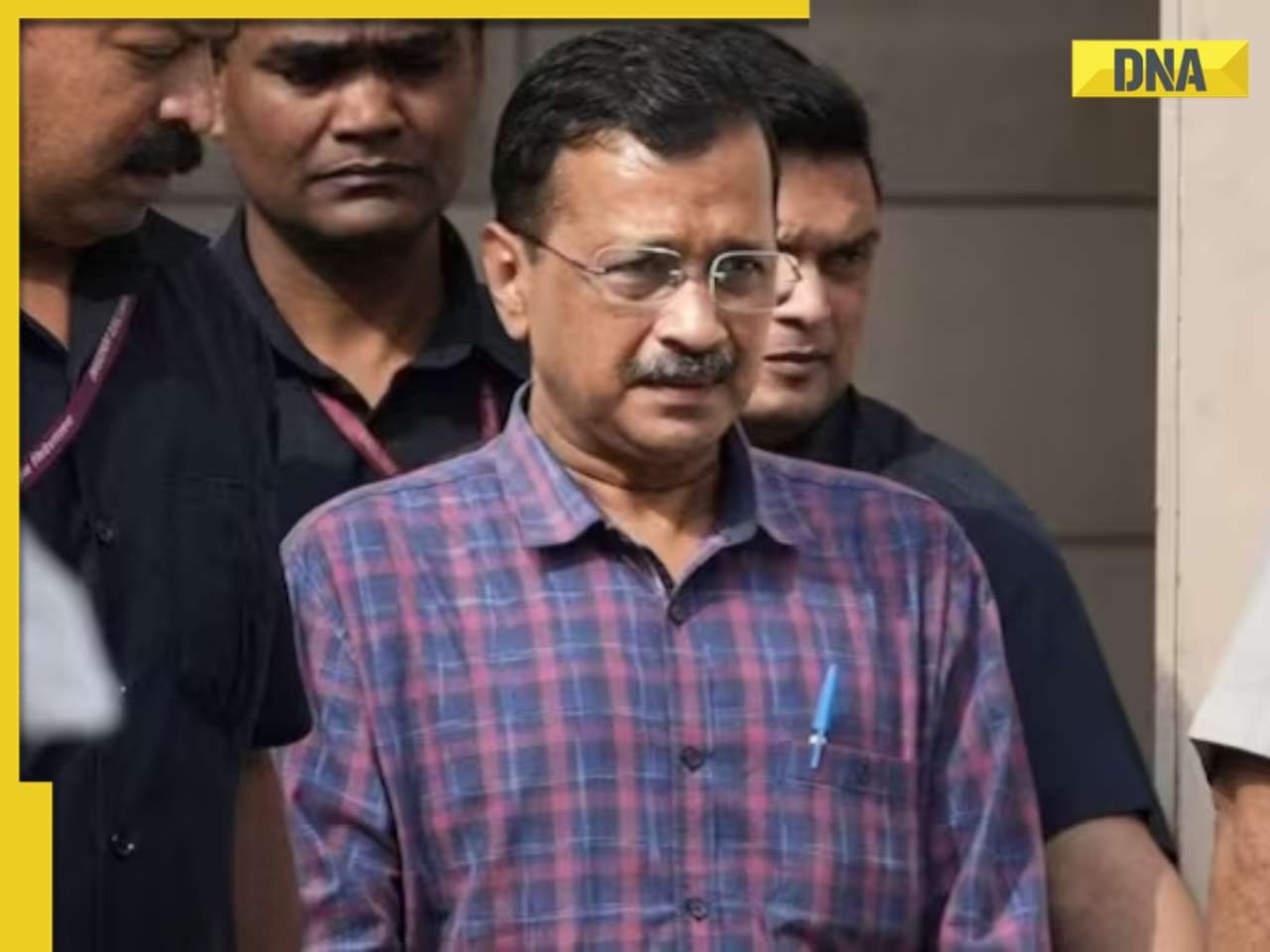

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

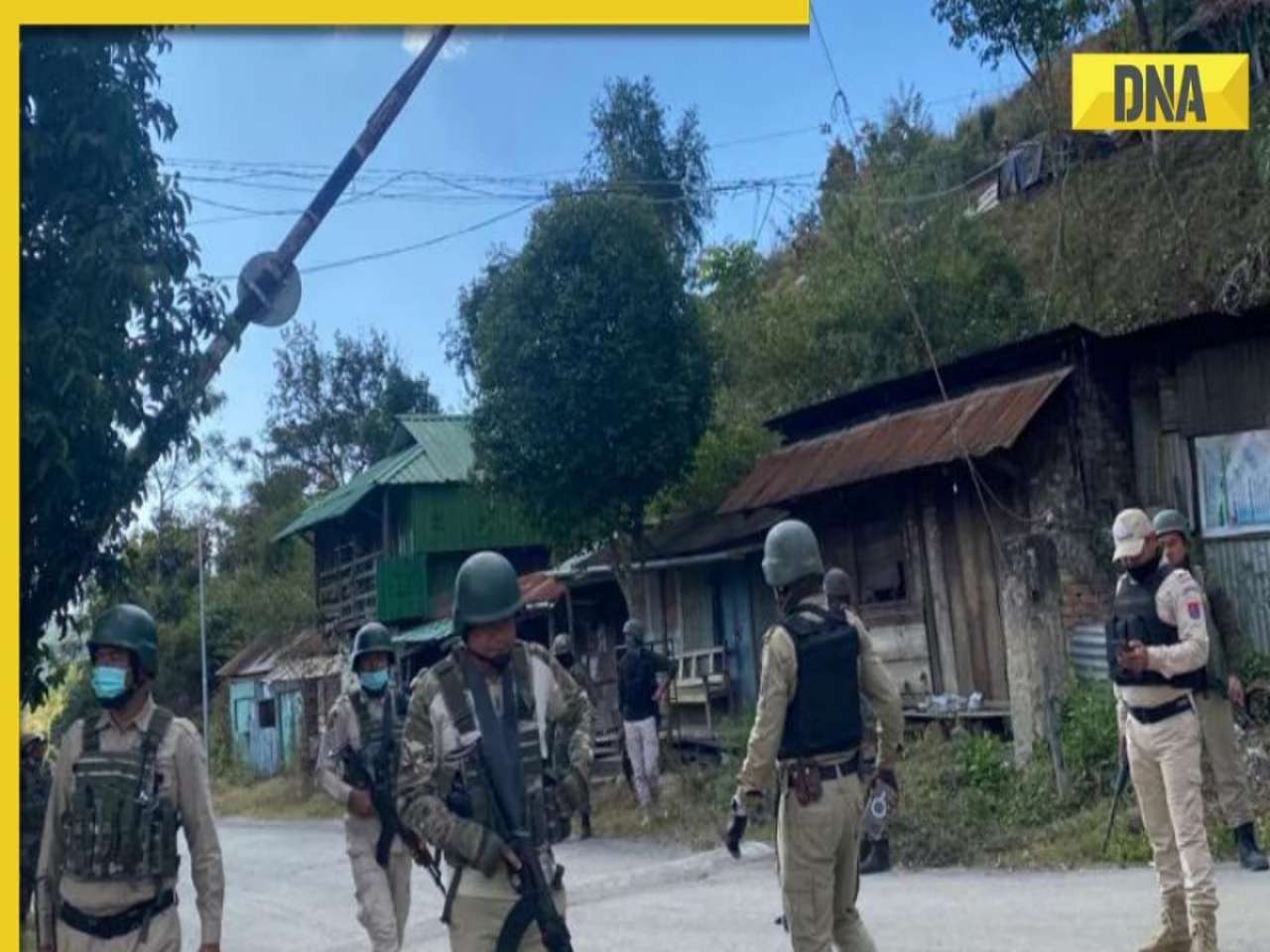

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)

)