A prominent figure of Kerala’s Valluvanad is disappearing from its cultural landscape: the velichappadu, or God’s oracle. Anu Prabhakar goes in search of the few remaining.

At the Puthanalkkal Bhagvati temple in small town Cherpulassery, the burning oil lamps are the main sources of light after dusk, as devotees whisper fervent prayers, drop money into huge silver donation boxes and end their visit with a sharp clang of the overhead bell.

It is in this flickering light that the velichappadu makes his appearance, emerging from the shadows. Flipping his grey, shoulder-length hair in an effeminate gesture, he stands in front of the deity with outstretched arms. As the devotees watch with bated breath, he wraps a red and gold coloured cloth over his white dhoti. Then he slips his feet through large anklets, ties a belt lined with tiny bells around his waist and walks briskly around the temple three times. In the semi-darkness, the bells sound divine.

By now, the velichappadu has his audience enraptured. Trembling slightly, he wields a large sword in front of them and whispers into somebody’s ear, leaving her looking pleased. Panting, he throws fistfuls of rice at the devotees and ends the day’s work by lightly touching their heads with his sword. The only jarring note comes towards the end of the ritual when I catch him looking closely at the donations that the devotees place on his sword, a few seconds longer than necessary.

Family fables

Family fables

The practice of instating a velichappadu (oracle of God) at temples is a phenomenon particular to the Kerala belt of Valluvanad, dotted with small towns like Ottapalam, Shoranur and Pattambi. Here, decades-old fables are handed down from one generation to another like precious heirlooms. The residents of one of the tharavads (ancestral homes) in Ottapalam that I visited recounted the story of how their great-grandmother rushed to the tharavad’s ancestral temple on learning that her only son had decided to fight in World War II. Overcome with hysteria, she shrieked at god, vowing not go home until her son returned. Two days later, the radio crackled with the news of Hitler’s suicide and her son returned home, unscathed.

The current residents of the tharavad are teachers, government employees and scientific researchers. Their faith in the tale, however, remains unshakeable. Every household in fact has a similar mythical tale to recount.

Decades ago in such towns, a fantastical figure like a velichappadu used to enjoy a lot of importance. His advice was believed to be the word of God himself. No one dared to challenge it. And a man being anointed as velichappadu was a matter of pride for the entire family.

Today, however, youngsters shy away from becoming a velichappadu and the few existing ones — who are in their 70s and 80s — talk about forming trade unions to fight for better salaries. With belief in the velichappadu wearing thin, only a few temples still follow the system. Out of earshot of the deity, the velichappadus themselves admit that it is a vanishing culture.

Changing mindset

It is a wet and humid day in Thozupadam, a small village in Shoranur. Seventy-four-year-old Kunjukuttan Nair curls his sweat-soaked hair into a bun, before proceeding to talk about his life as a velichappadu for 38 years, peppering the tale with recollections of feats like rubbing his body with fire. “My body became as black as coal but I didn’t get burnt,” says Kunjukuttan. ”God always saves me.”

A velichappadu inflicting bodily harm on himself during certain rituals is not uncommon. In the Kodungallur Bhagavati temple in Thrissur, the velichappadu, ‘possessed by the spirit of God’, shakes uncontrollably and bangs his forehead with a sword till blood trickles down his face. The pujari then rubs the wound with ash, which is believed to have miraculous healing powers. The next day, the velichappadu can be seen back at the temple, with his forehead intact.

Such rituals don’t have quite the same awe-inspiring effect as before, however. And while Kunjukuttan insists that there is no dearth of velichappadus in the village, one of the elders of the temple, who does not wish to be named, pooh-poohs this. “Which youngster would like to grow his hair long and walk around like this?” he asks. “They find it funny.”

Earthly matters

Back at the Puthanalkkal Bhagvati temple in Cherpulassery, Chandran Nair leads a simple life, depending on the offerings and donations of devotees for his livelihood. However, in certain temples, this is no longer allowed, with the Kerala Devaswom Board paying a salary instead. “I am paid Rs4,500 per month. I spend Rs50 to just commute to the temple from my house, which is 40km away. I have to sign the register at the temple every day, or else I will lose my day’s salary,” explains Kutty Krishnan, the velichappadu at the Ayyappan temple in Cherpulassery.

Kutty Krishnan hails from a family of velichappadus: his dad was one, his brother is one, and even his father-in-law was one. But now there are few takers for his profession. Besides the low salary, a rigid lifestyle discourages youngsters from taking it up. “If someone you know dies, you are not supposed to go to the funeral because you have surrendered your mind and soul to God. Who will be ready for all this?”

For somebody whose earliest childhood memories are of accompanying his father to various temples, Kutty Krishnan is pained to see the changing cultural landscape of Valluvanad. “One day, this will vanish altogether,” he says prophetically, as is his wont.

![submenu-img]() Balancing Risk and Reward: Tips and Tricks for Good Mobile Trading

Balancing Risk and Reward: Tips and Tricks for Good Mobile Trading![submenu-img]() Balmorex Pro [Is It Safe?] Real Customers Expose Hidden Dangers

Balmorex Pro [Is It Safe?] Real Customers Expose Hidden Dangers![submenu-img]() Sight Care Reviews (Real User EXPERIENCE) Ingredients, Benefits, And Side Effects Of Vision Support Formula Revealed!

Sight Care Reviews (Real User EXPERIENCE) Ingredients, Benefits, And Side Effects Of Vision Support Formula Revealed!![submenu-img]() Java Burn Reviews (Weight Loss Supplement) Real Ingredients, Benefits, Risks, And Honest Customer Reviews

Java Burn Reviews (Weight Loss Supplement) Real Ingredients, Benefits, Risks, And Honest Customer Reviews![submenu-img]() Gurucharan Singh is still unreachable after returning home, says Taarak Mehta producer Asit Modi: 'I have been trying..'

Gurucharan Singh is still unreachable after returning home, says Taarak Mehta producer Asit Modi: 'I have been trying..'![submenu-img]() RBSE 12th Result 2024 Live Updates: Rajasthan Board Class 12 results DECLARED, get direct link here

RBSE 12th Result 2024 Live Updates: Rajasthan Board Class 12 results DECLARED, get direct link here![submenu-img]() IIT graduate Indian genius ‘solved’ 161-year old maths mystery, left teaching to become CEO of…

IIT graduate Indian genius ‘solved’ 161-year old maths mystery, left teaching to become CEO of…![submenu-img]() RBSE 12th Result 2024 Live Updates: Rajasthan Board Class 12 results to be announced soon, get direct link here

RBSE 12th Result 2024 Live Updates: Rajasthan Board Class 12 results to be announced soon, get direct link here![submenu-img]() Meet doctor who cracked UPSC exam to become IAS officer but resigned after few years due to...

Meet doctor who cracked UPSC exam to become IAS officer but resigned after few years due to...![submenu-img]() IIT graduate gets job with Rs 45 crore salary package, fired after few years, buys Narayana Murthy’s…

IIT graduate gets job with Rs 45 crore salary package, fired after few years, buys Narayana Murthy’s…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024

Urvashi Rautela mesmerises in blue celestial gown, her dancing fish necklace steals the limelight at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'

Kiara Advani attends Women In Cinema Gala in dramatic ensemble, netizens say 'who designs these hideous dresses'![submenu-img]() Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024

Influencer Diipa Büller-Khosla looks 'drop dead gorgeous' in metallic structured dress at Cannes 2024![submenu-img]() Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera

Kiara Advani stuns in Prabal Gurung thigh-high slit gown for her Cannes debut, poses by the French Riviera![submenu-img]() Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’

Heeramandi star Taha Shah Badussha makes dashing debut at Cannes Film Festival, fans call him ‘international crush’![submenu-img]() Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?

Haryana Political Crisis: Will 3 independent MLAs support withdrawal impact the present Nayab Saini led-BJP government?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() Gurucharan Singh is still unreachable after returning home, says Taarak Mehta producer Asit Modi: 'I have been trying..'

Gurucharan Singh is still unreachable after returning home, says Taarak Mehta producer Asit Modi: 'I have been trying..'![submenu-img]() ‘Jo mujhse bulwana chahte ho…’: Angry Dharmendra lashes out after casting his vote in Lok Sabha Elections 2024

‘Jo mujhse bulwana chahte ho…’: Angry Dharmendra lashes out after casting his vote in Lok Sabha Elections 2024![submenu-img]() Deepika Padukone spotted with her baby bump as she steps out with Ranveer Singh to cast her vote in Lok Sabha elections

Deepika Padukone spotted with her baby bump as she steps out with Ranveer Singh to cast her vote in Lok Sabha elections![submenu-img]() Jr NTR surprises fans on birthday, announces NTR 31 with Prashanth Neel, shares details

Jr NTR surprises fans on birthday, announces NTR 31 with Prashanth Neel, shares details ![submenu-img]() 86-year-old Shubha Khote wins hearts by coming out to cast her vote in Lok Sabha elections, says meant to inspire voters

86-year-old Shubha Khote wins hearts by coming out to cast her vote in Lok Sabha elections, says meant to inspire voters![submenu-img]() Watch viral video: Man gets attacked after trying to touch ‘pet’ cheetah; netizens react

Watch viral video: Man gets attacked after trying to touch ‘pet’ cheetah; netizens react![submenu-img]() Real story of Lahore's Heermandi that inspired Netflix series

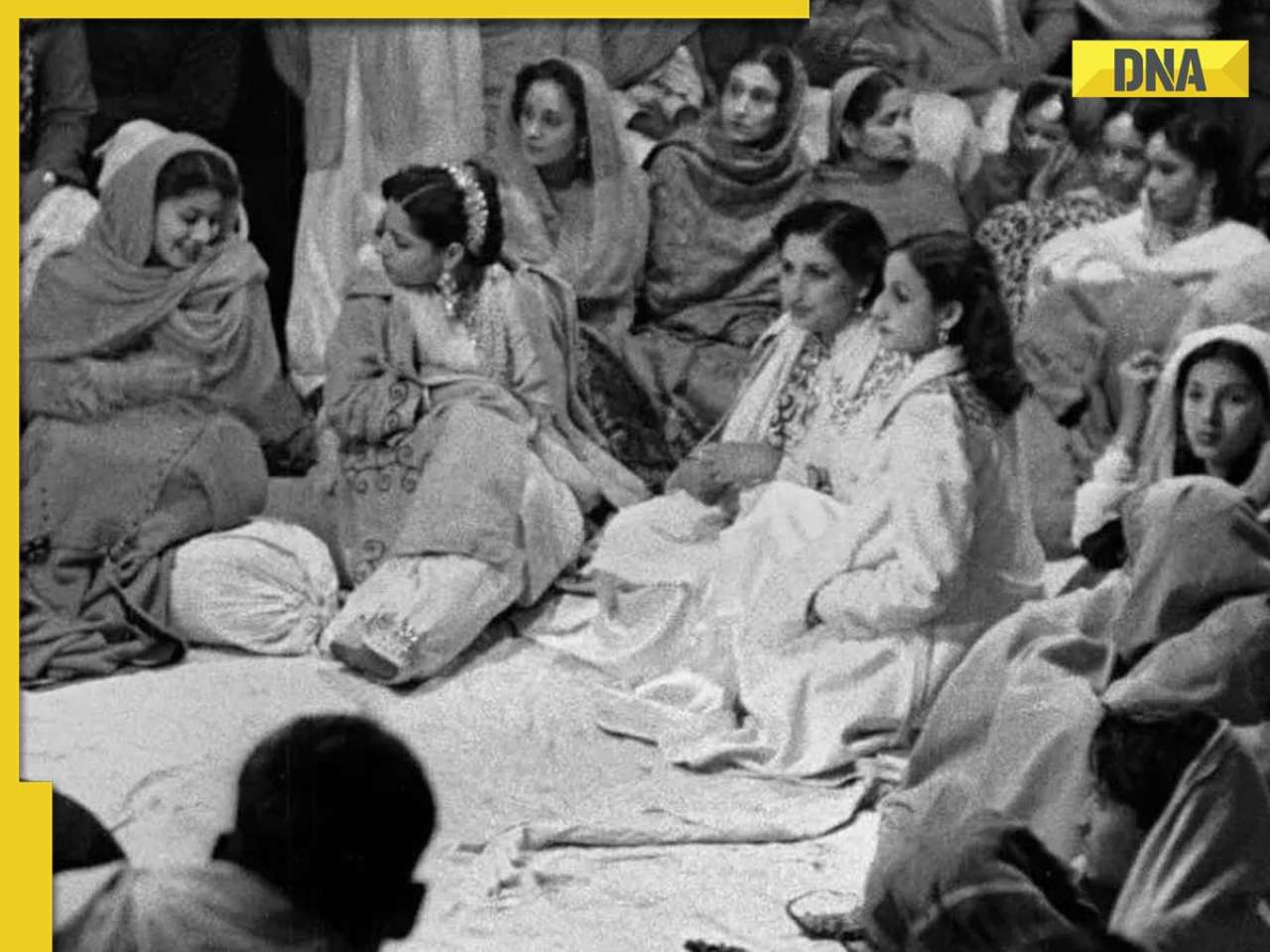

Real story of Lahore's Heermandi that inspired Netflix series![submenu-img]() 12-year-old Bengaluru girl undergoes surgery after eating 'smoky paan', details inside

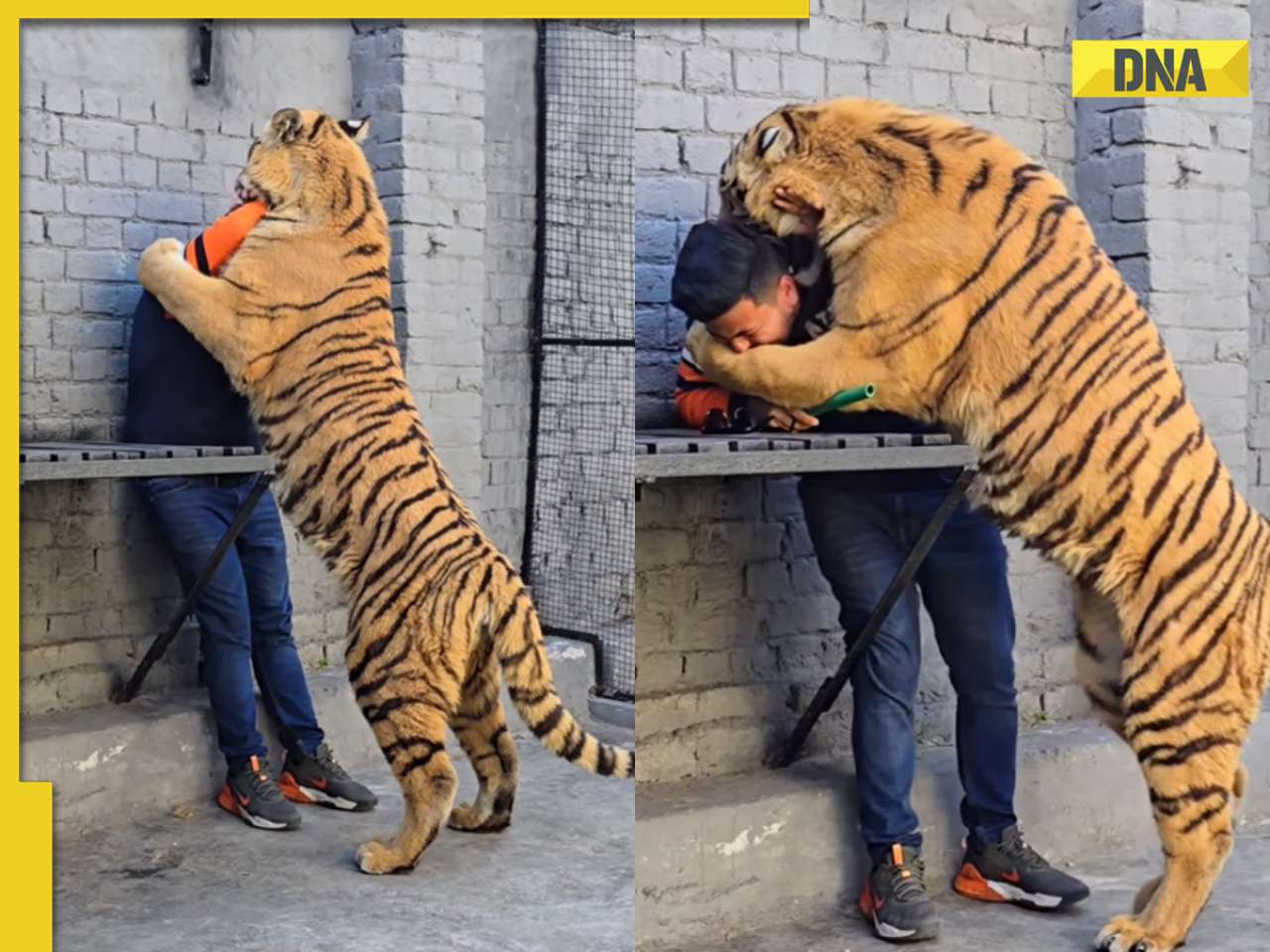

12-year-old Bengaluru girl undergoes surgery after eating 'smoky paan', details inside![submenu-img]() Viral video: Pakistani man tries to get close with tiger and this happens next

Viral video: Pakistani man tries to get close with tiger and this happens next![submenu-img]() Owl swallows snake in one go, viral video shocks internet

Owl swallows snake in one go, viral video shocks internet

)

) Family fables

Family fables

)

)

)

)

)

)