The former maharani of Jaipur, Gayatri Devi, was housed in Tihar jail in a small room with a veranda which was meant for visiting doctors. It had open sewers running along its side.

Book: The Emergency: A Personal History

Author: Coomi Kapoor

Publisher: Viking

Pages: 389

Rs: 599

It'll be exactly 30 years on June 25 since Indira Gandhi declared a state of Emergency, suspending civil rights and sending opposition leaders en masse to prison. Thousands were arrested in the dark days and nights that followed as Gandhi and her son Sanjay enforced sterilisation, 'beautification' drives that left thousands of people homeless overnight, and muzzled the press. An excerpt from journalist Coomi Kapoor's forthcoming memoirs of that dark interlude in the history of independent India:

The former maharani of Jaipur, Gayatri Devi, was housed in Tihar jail in a small room with a veranda which was meant for visiting doctors. It had open sewers running along its side. The room was already occupied by Shrilata Swaminathan, a dedicated NGO worker who had incurred the wrath of the authorities because she had organised farm labourers working on the plush farmhouses bordering Delhi. Rajiv Gandhi was one of those who owned a farmhouse in Chhatarpur, then an outlying region of the capital.

As an erstwhile royal, Gayatri Devi was given some special facilities by the Tihar jail superintendent – a newspaper along with her morning tea, and a fellow prisoner, Laila Begum, to clean her room. She was also allowed to take a walk in the evening with her stepson Major Bhawani Singh (Bubbles), who had been arrested along with her. These small concessions kept her going and insulated her to some degree from the terrifying world around her. Women prisoners were released only for two hours in the morning and two in the evening. 'It was like a fish market with petty thieves and prostitutes screaming at each other,' she recalled in her memoirs. Sympathetic friends from overseas sent all sorts of presents, from books and perfumes to chocolates and Christmas pudding. The maharani spent her days reading and embroidering. She also assisted the children of the convicts in getting textbooks and slates to start some lessons, and helped set up a badminton court. Gayatri Devi soon developed an ulcer in her mouth and it took three weeks for the authorities to permit her personal dental surgeon to visit her. It was several more weeks before the prison superintendent would allow her to be operated upon at the clinic of a well-known Delhi dentist, Dr Bery.

The internment of the Rajmata of Gwalior, Vijayaraje Scindia, was longer, but she was probably less traumatised by her experience than Gayatri Devi. 'There was a glow on her face. The Rajmata of Jaipur on the other hand looked haggard and shell-shocked,' recalls Virendra Kapoor.

In Tihar jail the two maharanis greeted each other in the traditional style of the heads of two royal houses, with bowed heads and folded hands, when they first met. But Gayatri Devi could not help bursting out, 'Whatever made you come here? This is a horrible place.'

Vijayaraje's cell was at the very edge of the women's ward. It was a small, narrow room with a high, barred window. The common bathroom had no tap. A hole in the ground, covered with a plank, served as a toilet and a sweeper came twice a day to flush it with a bucket of water. There was an all-pervading stench, ever-present flies and mosquitoes and perpetual noise. The location of her cell, between the men's and women's wards meant that she got to hear the sounds from both sides. The women inmates engaged in frequent slanging matches, with their children constantly howling; from the other side of the wall came the sounds of political slogans and patriotic songs as well as demented screams and maniacal laughter.

The maharani bore these conditions stoically. She tried to make the best of the situation, drawing strength from her regular reading of the scriptures. For a month her family had no idea of her whereabouts. Vijayaraje used her time in jail to try and improve the lot of her fellow prisoners. She acted as mother confessor and confidante to many of them. A prisoner accused of murder was assigned as her personal maid and the woman looked after her with great dedication. Vijayaraje instructed her daughters to bring clothes for the children, as well as cough syrups and sweets. She also taught the prisoners to sing bhajans as a change from their usual repertory of film songs, which they referred to as cabaret numbers. When Vijayaraje finally left the prison, the female convicts lined both sides of the entrance to the inner gate and strewed her path with petals to show their gratitude.

(Reproduced with permission from the publishers)

![submenu-img]() Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here

Weather update: IMD predicts light to moderate rain, thunderstorms in Delhi-NCR; check forecast here![submenu-img]() 'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...

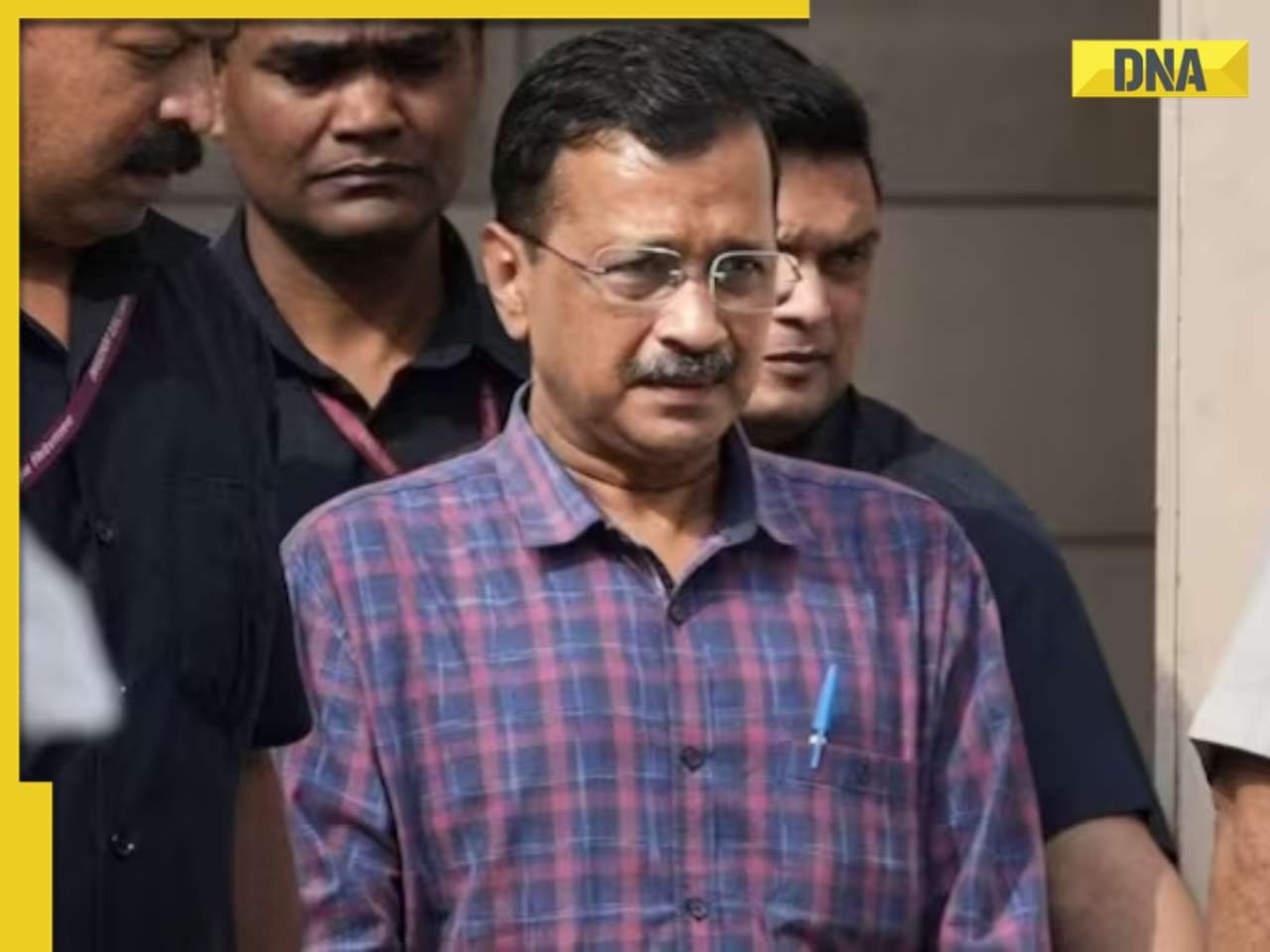

'I can't breathe': Black man in Ohio pleads as police officers pin him to floor, then...![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

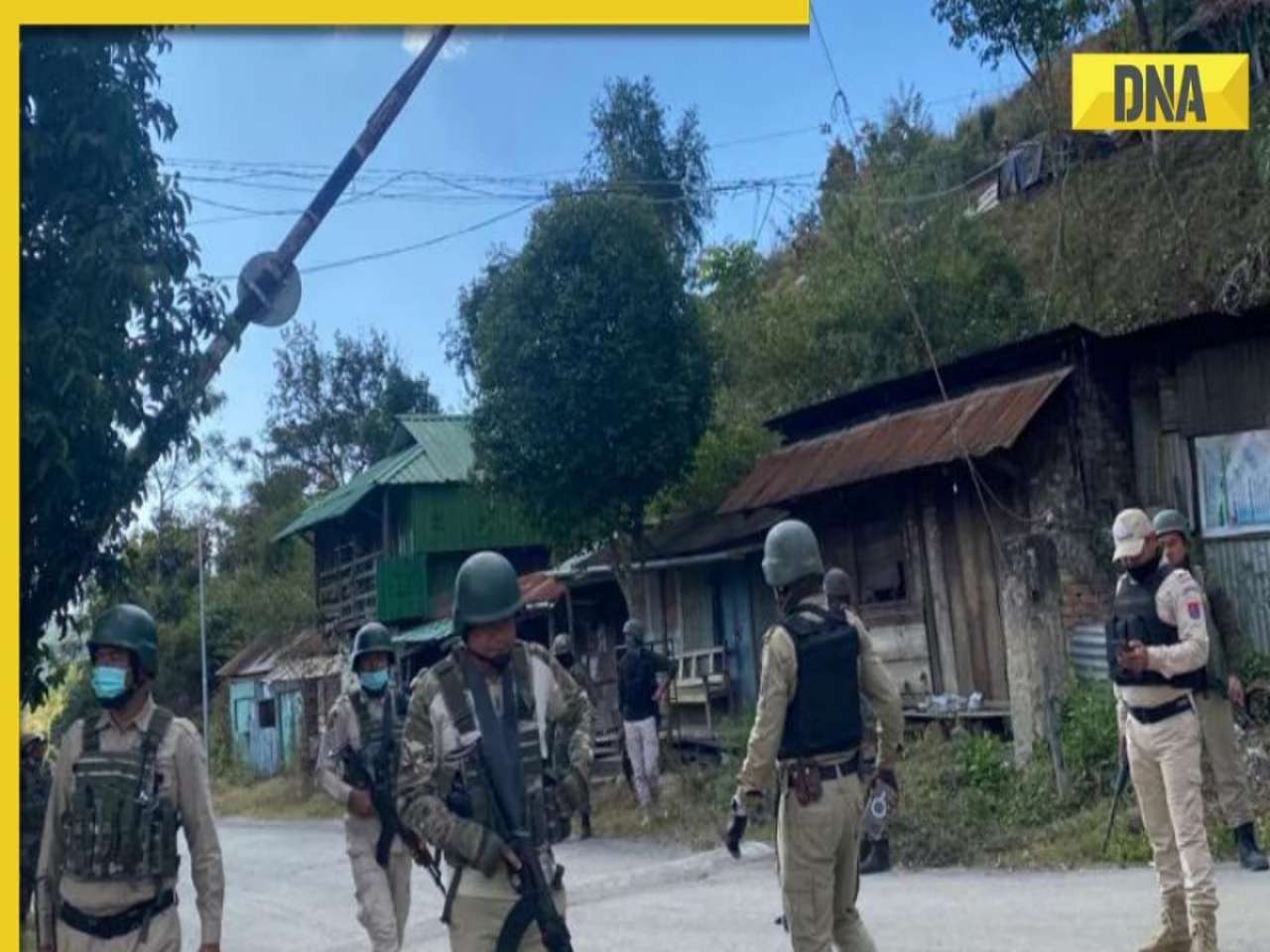

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)

)