The lifting of the ban in the US on human embryonic stem cell research has already had a ripple effect in India, but there’s still a distance to go.

The lifting of the ban in the US on human embryonic stem cell research has already had a ripple effect in India, with new possibilities of collaboration opening up and raising hopes of ‘miracle cures’ for everything from diabetes to Alzheimer’s. But there’s still a distance to go before research can translate into new therapies.

Sometimes hope can be a bad thing. A few years ago, Karan Goel, the head of pharmaceutical firm in Delhi, who was left almost blind by a disorder called retinitis pigmentosa in his teens, decided to try and get his sight back. The 28-year-old had tried both drugs and surgery, without success.

Then, in 2003, he heard about a new retinal stem cell transplant that would help the damaged photoreceptors in his eyes grow back, and partially restore vision. Goel headed to Mexico, one of the few countries offering this procedure. But shortly into the treatment, Goel realised it wasn’t working. “I had hoped it would help, but eventually I had to abandon the process,” he says. “There seems to be no technology on the planet for retinal stem cells.”

Goel’s disappointment is not surprising. New possibilities emerge everyday in stem cell research, raising hopes among chronically ill people in despair. But there’s a wide gulf between research and actual treatment, which is still at a nascent stage.

From time to time, doctors report cases of people who have responded to stem cell therapy, but these can at best be seen as encouraging signs. Bigger clinical trials are needed to validate the therapies. Sometimes, a patient may show a dramatic improvement, only for it to disappear after a time. Adding to the confusion are the many bogus claims of miracle cures being made by fly-by-night clinics and websites, feeding off the excitement in the media over the potential of stem cells.

To be sure, stem cell research is in fact making dramatic progress, especially now that Barack Obama has lifted a ban on experimenting with embryonic stem cells (see box). The Obama go-ahead has given a major push to research in India too, with new funds and collaborations.

“We have already been doing research with embryonic stem cells, now we’ll do much more of it,” says BN Manohar, head of the Bangalore-based Stempeutics, a wing of the Manipal group of hospitals. “In time, may be over seven or eight years, this research will mature into application, and can become a source for drugs for a variety of ailments.”

These can lead to treatment of genetic and muscular disorders, degenerative nerve ailments like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, lifestyle-related problems like diabetes and cancer, liver and kidney ailments like cirrhosis and hepatitis, corneal and retinal disorders and glaucoma, and congenital problems in children, like heart disease and Type I diabetes. Earlier this month, Stempeutics received approval to find drugs to prevent artery blockages and heart attacks.

According to N Chandramouli, CEO of the stem cell bank Cryosave India, which recently received a 2 million euro grant for stem cell banking and research from its European parent body, 85 diseases have been identified with potential for stem cell treatment, and researchers are looking for more. “We are in touch with Cryosave’s labs in France and Germany; so whatever cutting-edge research takes place there, will soon come to India,” he says.

Doctors are also looking for new sources for cells, aside from the three primary ones: Embryonic, or stem cells drawn from a foetus (a process that the Bush administration had banned); adult cells, extracted from the bone marrow of a patient, and the most effective source, blood from the umbilical cord, or cord blood. Cryosave researchers are now looking at taking cells from adipose tissues, while labs at Christian Medical College, Vellore, recently claimed to have replicated a human cell line drawn from the cells of mice.

Cord blood banks, that offer to store cord blood for patients for up to 20 years, are also becoming popular. Medical student Sheetal Gulati first heard about this from her gynaecologist. Shortly after her delivery six weeks ago, she got in touch with Cryosave and stored the cord blood as a precautionary measure for her infant son. “If he ever has an accident or a life-threatening disease, doctors can use the cord blood for a stem cell cure,” says Gulati. India has six private banks, and last month got its first public bank too, in Chennai.

“Now anyone can approach the bank for a match among the stored cell lines,” says Goel, who runs the NGO, Stem Cell Voice of India.

New centres for R&D are mushrooming, and established hospitals have started offering stem cell treatment in accidents, cardiology and diabetes. The Lokmanya Tilak General Municipal Hospital, Sion, which opened its stem cell department in September last year, has carried out around 50 procedures since then — mostly for spinal cord injuries.

“Stem cell therapy can make a dramatic difference to those incapacitated by an accident,” says Dr Alok Sharma, head of the hospital’s stem cell department.

A case in point is Nashik trader Mukesh Kothule, 28, was paralysed, neck down, after a car crash. He was bedridden for 17 months, unable to move his limbs or speak. He arrived at LTMGH for treatment in November. Dr Sharma and his team removed some bone marrow from Kothule’s thigh, extracted cells and injected them into the affected area.

Now Mukesh can sit in a wheelchair, move his arms, lift and clutch things with his hands, and even stand for an hour with support. “The first thing I did when I got some sensation back in my fingers, was write my name,” says the dairy owner. “Soon I’ll be walking out of this hospital on my own.”

At the same time, an official from the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR), which has to approve all research and trials conducted in India, sounds a word of caution. “Stem cell therapies are still experiments, and patients need to be warned that there may be side-effects,” the official says. “Everybody’s learning here.” ICMR has strict guidelines to curb dubious procedures, but these have yet to become laws.

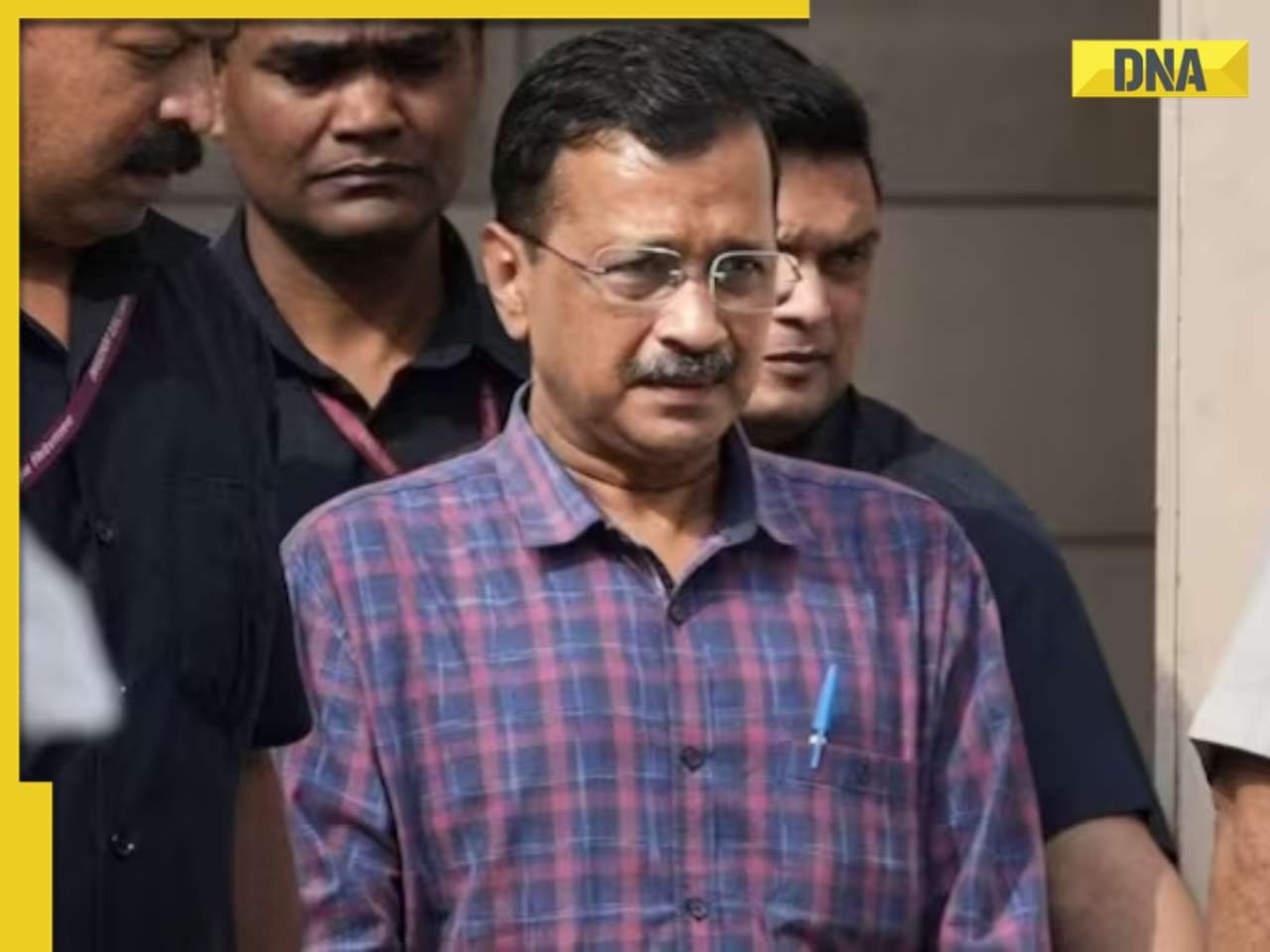

![submenu-img]() Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest

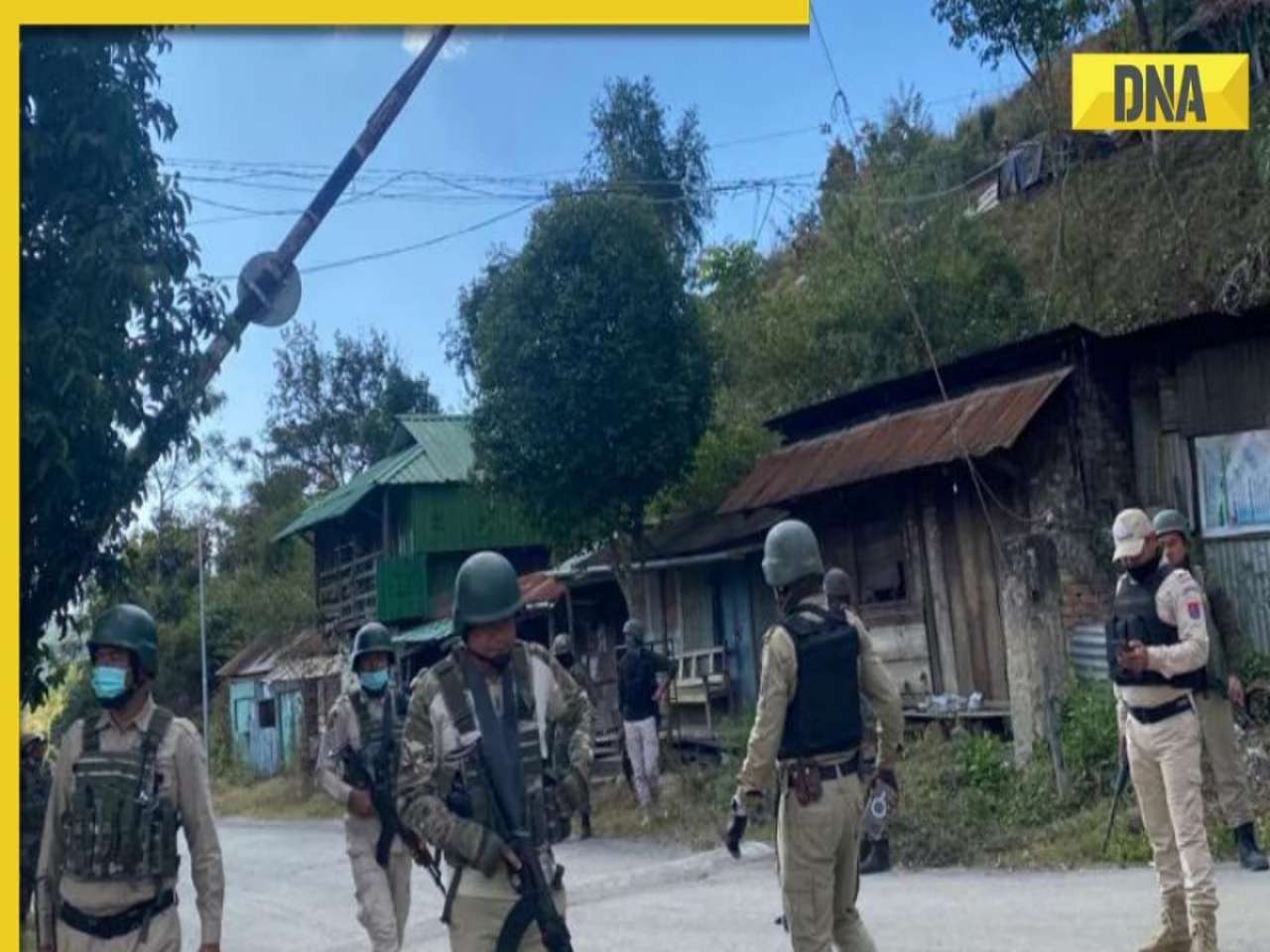

Delhi HC raps CM Kejriwal, accuses him of prioritising political interest by continuing as CM after arrest![submenu-img]() Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area

Manipur: Two CRPF personnel killed in Kuki militants' attack in Naransena area![submenu-img]() These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’

These 9 Indian dishes make it to the list of ‘best stews in the world’![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'

DNA Verified: Is CAA an anti-Muslim law? Centre terms news report as 'misleading'![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message

DNA Verified: Lok Sabha Elections 2024 to be held on April 19? Know truth behind viral message![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here

DNA Verified: Modi govt giving students free laptops under 'One Student One Laptop' scheme? Know truth here![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar

DNA Verified: Shah Rukh Khan denies reports of his role in release of India's naval officers from Qatar![submenu-img]() DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth

DNA Verified: Is govt providing Rs 1.6 lakh benefit to girls under PM Ladli Laxmi Yojana? Know truth![submenu-img]() In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding

In pics: Arti Singh stuns in red lehenga as she ties the knot with beau Dipak Chauhan in dreamy wedding![submenu-img]() Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries

Actors who died due to cosmetic surgeries![submenu-img]() See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol

See inside pics: Malayalam star Aparna Das' dreamy wedding with Manjummel Boys actor Deepak Parambol ![submenu-img]() In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi

In pics: Salman Khan, Alia Bhatt, Rekha, Neetu Kapoor attend grand premiere of Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi![submenu-img]() Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch

Streaming This Week: Crakk, Tillu Square, Ranneeti, Dil Dosti Dilemma, latest OTT releases to binge-watch![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?

DNA Explainer: Why Harvey Weinstein's rape conviction was overturned, will beleaguered Hollywood mogul get out of jail?![submenu-img]() What is inheritance tax?

What is inheritance tax?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?

DNA Explainer: What is cloud seeding which is blamed for wreaking havoc in Dubai?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?

DNA Explainer: What is Israel's Arrow-3 defence system used to intercept Iran's missile attack?![submenu-img]() DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence

DNA Explainer: How Iranian projectiles failed to breach iron-clad Israeli air defence![submenu-img]() Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'

Krishna Mukherjee accuses Shubh Shagun producer of harassing, threatening her: ‘I was changing clothes when...'![submenu-img]() Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…

Meet 90s top Bollywood actress, who gave hits with Shah Rukh, Salman, Aamir, one mistake ended career; has now become…![submenu-img]() This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…

This actress, who once worked as pre-school teacher, changed diapers, later gave six Rs 100-crore films; is now worth…![submenu-img]() 'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career

'There were days when I didn't want to probably live': Adhyayan Suman opens up on rough patch in his career![submenu-img]() This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan

This low-budget film with no star is 2024's highest-grossing Indian film; beat Fighter, Shaitaan, Bade Miyan Chote Miyan![submenu-img]() World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...

World wrestling body threatens to reimpose ban on WFI if...![submenu-img]() IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR

IPL 2024: Jonny Bairstow, Shashank Singh special power Punjab Kings to record run-chase against KKR![submenu-img]() DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

DC vs MI, IPL 2024: Predicted playing XI, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians

DC vs MI IPL 2024 Dream11 prediction: Fantasy cricket tips for Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians![submenu-img]() Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador

Yuvraj Singh named ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2024 Ambassador![submenu-img]() Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral

Watch: Lioness teaches cubs to climb tree, adorable video goes viral![submenu-img]() Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch

Viral video: Little girl's impressive lion roar wins hearts on internet, watch![submenu-img]() Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport

Who is Sangeet Singh? Man arrested for posing as Singapore Airlines pilot at Delhi airport![submenu-img]() One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…

One of India’s most expensive wedding, attended by 5000 people, 100 room villa, cost Rs…![submenu-img]() Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

Viral video: Delhi's 'Spiderman' take to streets on bike, get arrested; watch

)

)

)

)

)

)