In our piece on birth of a language last week, we spoke about spread of ‘Zaban-e-Dehli’ or Hindavi to Gujarat, Daultabad or Deogiri to Telengana to Golcunda, Bijapur and to Gulbrga. We also talked about how traders and travellers speaking a range of Central Asian languages helped the creation of Saraiki, the language of the Caravanserai, which was to evolve into the language of the Sufis of Punjab,

In this piece, we talk of the other sites where this mixing was taking place, the nurseries where a new language was gradually taking shape. There were at least four other sites where this mixing together of diverse linguistic and cultural resources was taking place, in the market, in the workplace of the artisans, the shrines of the Sufis, and in the battlefields.

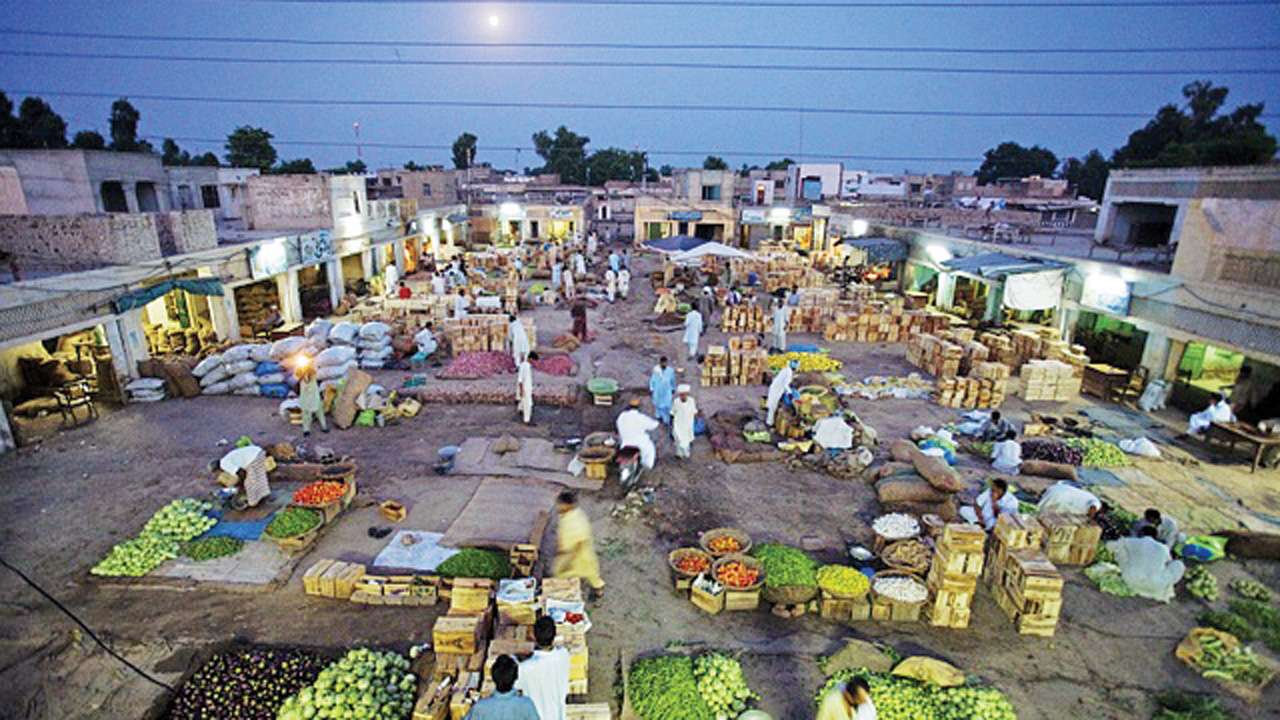

The markets across the dusty plains of north and central India were teeming with traders from all parts of Central Asia, and they arrived with their languages: Turkish, Persian, Dari, Pashtoon, Uzbek, Tajik and others, and words like gaz, tarazoo, wazan, girah, band-o-bast, raah, karwan, intezaam, sarai, nizam, raahi, naan, tanoor, jalebi, samosa, jama, dastar and jubba, qaleen, takht, malik, mulk, qaum and others began to be incorporated in the local languages.

From the time of Al’a ud Din Khilji, large workshops were set up where artisans, weavers, iron smiths, gold and silver smiths, embroiderers and tailors began to work together, producing not only large number of robes of cotton, silk and silk with gold and silver threads and brocades, but also words like darzi. They also produced swords inscribed in gold and silver and daggers encased in jewels and studded with precious stones. They also produced terms like kaargar, sangtarash, rangrez, aahangar, gareban, jeb, aaasteen, daaman, saafa, attar, zardoz, shamsheer, khanjar, teer-o-tafang, sandooq, dastkaari and dastkaar, while others began to be incorporated in the spoken language of the ‘kaarkhaana’.

Then came the Sufis with their message of Love. ‘Sulah-Kul’ wanted to reach out to the large numbers of their devotees in the languages of the people, and so the shrines of the Sufis turned into another nursery. Here, nazar, nazrana, langar, zakat, zikr, haazri, aqeedat and words that talked of ibaadat and wujood and space (makan) and non-space (laamakaan), and of being (khudi) and non-being (bekhudi) and such like became words of daily exchange. Nizam-ud-Din Auliya asked his favourite disciple — the polyglot, musician, singer, historian and poet, Amir Khsrau — to write in the language of the people, and the poetry of Khusrau that drew from Punjabi, Saraiki, Braj, Awadhi and other language contributed in a major way to the evolution of this language of Delhi.

So there are these peaceful exchanges in the Caravansrais, the Karkhanas, in the Bazaar and in the Khanqhaahs — the hospices of the Sufi — and simultaneously, there is war. Those seeking to build empires and those seeking to save their empires fought ceaselessly. Many of the commanders in the service of the adversaries spoke Central Asian languages while the soldiers spoke Braj, Awadhi, Maithili, Bhojpuri, Bundelkhandi, Malwi, Rohelkhandi and a diverse mix of other languages. The need to issue orders and to have them understood led to the evolution of a language of the Army camp, the Lashkar and thus emerged Lashkari: The language of the army camp. The soldier too went to the market, to the shrines of the Sufi while his brothers worked in the Caravanserais and in the Kaarkhaanas and so the languages that were in all these places began to mix and to get enriched and evolved into a language that gradually began to evolve into the lingua franca of the street, the bazaar, the khaanqaah and the battlefield. With the constant movement of all these people, it gradually evolved into a language that held sway from Delhi to the Deccan, acrss lands of the five rivers and the vast plains irrigated by the Ganga and the Jamna.

Taking advantage of the collapse of the Delhi Sultanate as the Timurid army sacked Delhi in 1398, the rulers of Golcunda and Bijapur broke away from the Delhi Sultanate and adopted Deccani as their official language. The 300 years from the sack of Delhi by Timur at the end of the 14th century to the end of the reign of Aurangzeb in the first decade of the 18th century were to play a crucial role in the evolution of Braj at Agra and of Deccani, the mother of Urdu and Hindi, in Deccan. This is what we will talk about next week in Part III of this piece.

The author is a historian