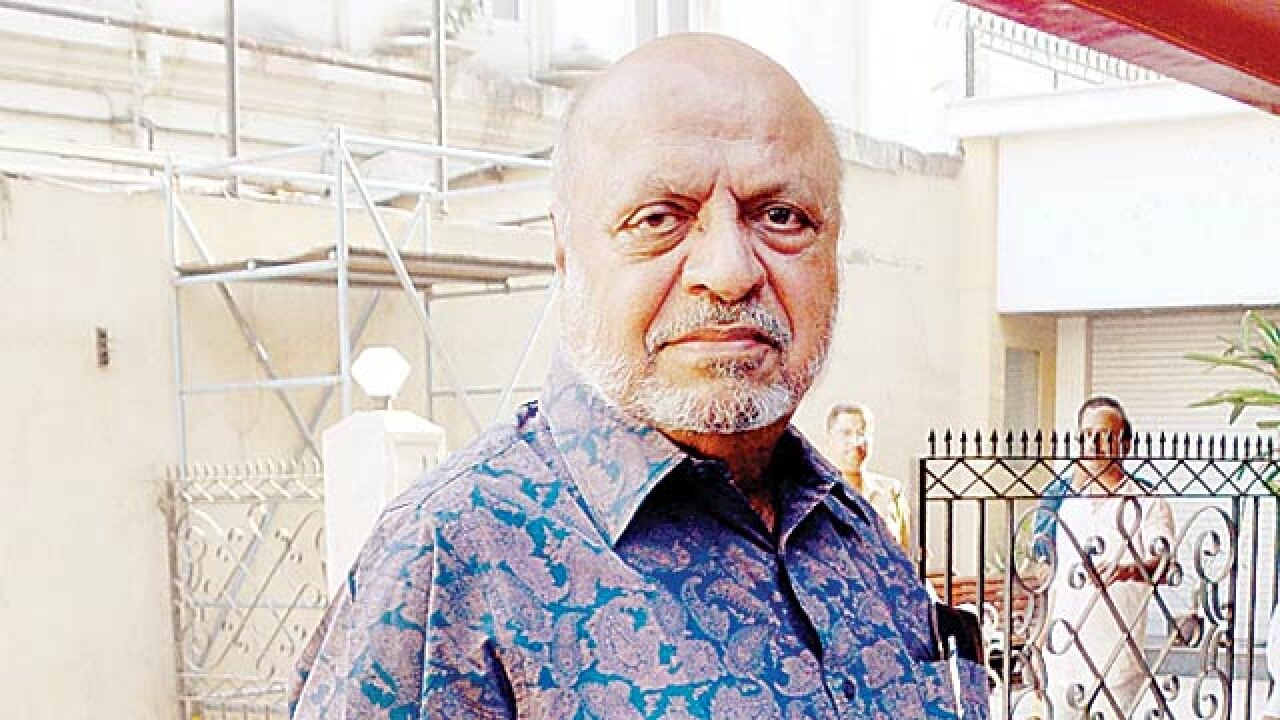

If the Centre truly wants to refurbish its image — and there is an urgent need for that — it should begin with implementing the suggestions proposed in the Shyam Benegal committee report pertaining to the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). In his tenure as the CBFC chairman, Pahlaj Nihalani’s puritanical approach has wreaked havoc to a powerful medium. He has wielded the archaic Cinematograph Act 1952 as the Norse god would use his hammer in a combat. His exasperating zeal to rid films of “malignant influences” has sent directors and writers into a tizzy. They have been forced to tailor their expressions to the chairman’s diktats. The CBFC’s stated aim to “ensure good and healthy entertainment in accordance with the provisions of the Cinematograph Act 1952 and the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules 1983” has, in fact, led to a reign of terror, presided by Nihalani.

But the rot in CBFC is systemic for which Nihalani alone should not be blamed. While scenes on sex, nudity and profanity were chopped off because of the CBFC taking the moral high ground, cases of misogyny and mindless violence were deliberately overlooked. CBFC, a statutory body set up under Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, gradually became a symbol of a repression — not to mention the allegations of corruption levelled against some of its members.

The committee headed by Benegal, a veteran filmmaker, has proposed a slew of changes, the most important of which is stripping the censor board of its ‘snipping’ powers. That can only come about if the committee’s recommendations for amendments in several sections of the 1952 Act are carried out. Once section 4(iii) of the act is amended, the certification body will cease to play god, much to the collective sigh of relief of the film fraternity, which has repeatedly argued and fought for freedom of expression. The committee’s suggestion that the same collective cannot be part of both the examining committee, and the revising committee, will give more opportunities to filmmakers to fight against the proposed cuts and modifications. It should ideally also encourage film-literate people to be part of the committees since a majority of those occupying key positions in the board have limited exposure to contemporary cinema.

Films being intensely subjective, these committees have all along stifled creative expression in the name of political correctness and majoritarian view, leaving filmmakers with very few options but to accede to their diktats.

One option is to challenge the decision in a court of law, which directors and producers are loath to since it’s a time consuming process resulting in release dates being pushed back. More importantly, till the case is resolved there is no way to recover the money invested in the film.

In the new scheme of things, the process of appeals, suspension and revocation are likely to help filmmakers like never before.

The Benegal committee report was preceded by Justice Mukul Mudgal panel’s suggestions in 2013 that had proposed a draft Cinematographic Bill. Now these two sets of recommendations will be carefully studied by the I&B ministry, which then plans to bring about the amendments through an ordinance. The existing laws being suitably vague, the CBFC, in a position of supreme authority, has interpreted them according to its convenience. The Benegal Committee report has tackled these loopholes to come up with the roadmap for a complete overhaul.

This could well be the first significant step at the institutional level to change the mediocre film culture in the country.