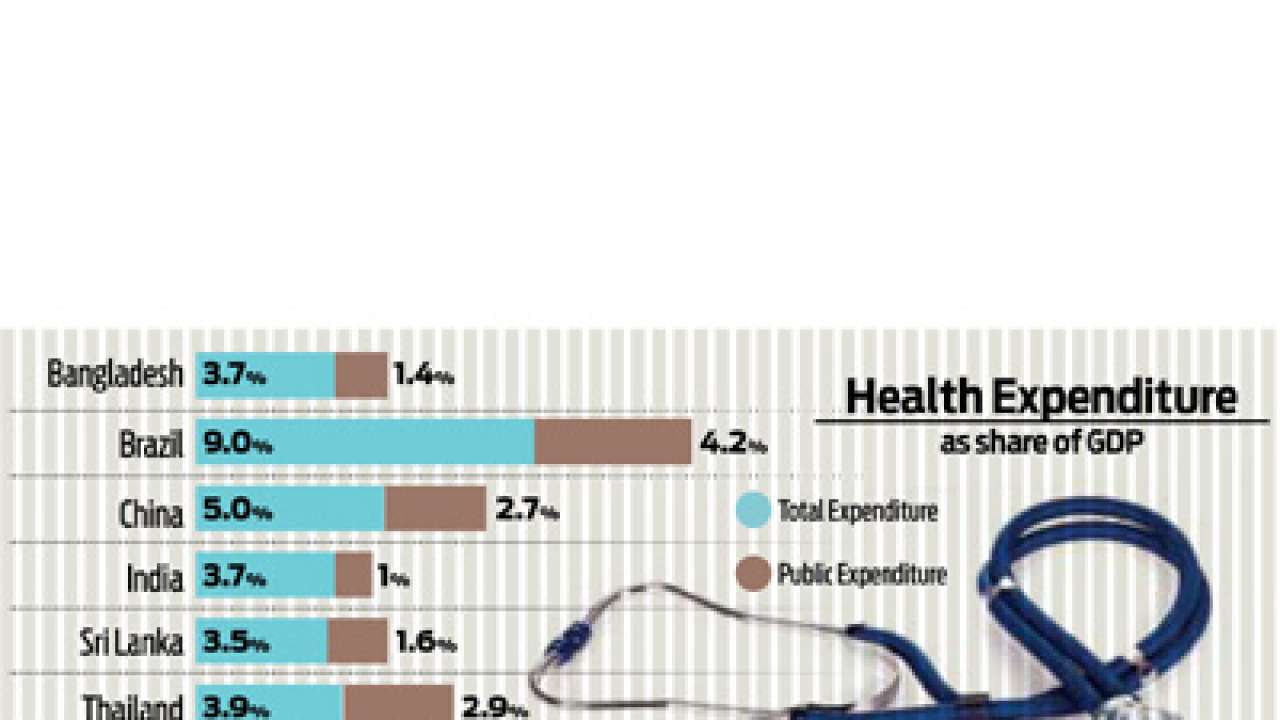

The recently published IDFC’s “India Infrastructure Report 2013-14” sums it up quite aptly. It points out how India’s health services are characterised by low expenditure on health. It underscores the fact that total health expenditure (both private and public) is less than 4% of its GDP. What is even more shocking is that, of this amount, public expenditure on health is an abysmal 1% of GDP.

Poor inputs, poorer output

And of the little investment in healthcare, the share of central and state governments in total health expenditure is just around 28%. Worse still, public spending is “more input-oriented with limited focus on outcomes”.

As a result, India’s public healthcare services are plagued with “inadequate and antiquated infrastructure with poor service quality”. The report talks of how there is a tremendous shortage of health infrastructure in rural areas, with shortage of facilities in all centres – sub-centres, primary health centres (PHCs), and community health centres (CHCs).

Even in a densely populated country like India, there is a severe shortage of human resources. There is understaffing of doctors at PHCs by around 10%, pharmacists at PHCs and CHCs by 18%, laboratory technicians at PHCs and CHCs by 43%, nursing staff at PHCs and CHCs by 23%, and specialists at CHCs by over 70%.

The consequence is that, for a population with limited purchasing power, India’s policymakers have compelled them to become more dependent on an increasingly rapacious private sector.

What often remains unsaid

All the numbers in the report paint a pretty depressing picture. But what the report does not say is how the best of this meager public expenditure on health services is often grabbed by the employees of the government sector, or even more significantly by the relatives and friends of powerful bureaucrats and politicians.

Go to any government hospital. Check out the list of patients in special wards or private rooms. You will discover that most of them are patients recommended by the powerful. It is a system that protects those connected with the powerful, leaving the rest of the population to fend for itself.

This is certainly not what was meant by the words “Sovereign Socialist, Secular, Democratic Republic” that were inserted into India’s Constitution (42nd Amendment in 1976 instead of the original “Sovereign Democratic Republic”). Ironically, much of the distortion of an egalitarian society began when Indira Gandhi was India’s prime minister, who contributed tremendously towards making a mockery of India’s socialist pretentions. India’s health services are ample testimony to this fact.

Consider, again, how even recently, in September 2013, the government of India stunned most common people with the announcement that the top officials of the Indian Administrative Service, the Indian Police Services and Indian Forest Service – and their family members -- could henceforth avail of medical treatment abroad at government expense (http://www.dnaindia.com/money/report-policy-watch-overseas-medicare-for-bureaucrats-a-terrible-retrograde-decision-1971679).

By taking this decision – reportedly at the instructions of one of the most powerful citizens of India in order to benefit one of her key advisors – the government was giving the powerful one more excuse not to have a stake in the healthcare system that the rest of the country had to live with.

Ministerial pomp

Take the manner in which ministers get reimbursed all their medical expenses – at the cost of taxpayers – at the fanciest of private hospitals.

Private hospitals are preferred because (a) the infrastructure at government hospitals is often poorer than at private hospitals, (b) the quality of doctors at most government hospitals is often inferior to that of doctors at private hospitals (no minister would like to be operated by a doctor who owes his position to a reservation policy that often ignores merit); and (c) it makes the powerful feel pampered as the bills are being paid by a public that does not have easy access to such facilities.

Even so, the powerful have sought to further wreck healthcare in India. Watch how one state government after another has tried to whittle down the number of post graduate (and undergraduate) seats in government run medical colleges. Mercifully, the courts intervened in some cases. As a result, private medical colleges (most run by the powerfully connected) benefited from the hefty fees (and donations) that they charge.

Damnation for the rest

Think of how most government medical colleges actually drove out the best of honorary medical faculty on the flimsy ground that they had private practice of their own. The result, even the little talent that was available to train future doctors, and to tend to poor patients, could now be availed of, and paid for, at private clinics.

Take at the look at the absence of a proper regulator for the quality of services and fees that private clinics and hospitals should charge. It is absurd that the country has a central regulator for markets, competition and even insurance, but none for education and healthcare – the two key inputs that can make or break a nation’s population and human resources.

For instance, had the government mandated that ministers and senior bureaucrats be treated at government hospitals only, they would have found a way to improve these services.

Or take another instance. The government could have allowed medical insurance companies to take up an equity stake in key diagnostic centres so that those having insurance policies could get their medical checkups at half the market cost. That would have helped people take care of their lifestyles, thus minimising the risk eventually borne by medical insurance companies.

Unfortunately, none of this has happened. As a result most common people dread illness. They know that one major ailment in a middle class or poor home can bankrupt an entire family for decades.

This does raise the question: What is the use of banning mercy killing, without first penalising policymakers who neglect the amelioration of living conditions when they are most needed? The absurdity is galling.

It is equally sad that India’s courts have not raised this issue that is so critical to the growth and image of an entire society and country.

The author is a consulting editor with dna