Financial reform is like a big onion. The more layers you peel off, the harder you cry,” said Cornell University law professor Saule Omarova. This is especially true of the Benami Transanctions (Prohibition) Amendment Act, 2016. Benami property means any property purchased with black money or in the name of another person to hide the real ownership of the property. A 2012 report by the Central Board of Direct Taxes said: “It is observed that demonetisation may not be a solution for tackling black money or economy, which is largely held in the form Benami properties, bullion and jewellery.” It is a well recognised fact that the generation of black money is a continuous process. The same black money re-enters the system as the ‘white’ economy in a laundered form.

The Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act was enacted in 1988, three years before the economic reforms of 1991. The 1988 Benami Act had no provision for vesting of confiscated property with the central government. The policymakers did not want any check and balances which block the free flow of money and the Act became toothless. The two-page act became a static allegory for the dream of a transparent tax system. After the 2008 economic crisis, governments were forced to rethink deregulation and the free market concept. States realised the need to respond to growing cases of tax evasion. Finally, on November 1, 2016, a week before demonetization, the 28-year-old Benami Act was replaced by a comprehensive legislation.

The new Act uses strong and clear wording and has provisions to punish those who defy the demonetisation drive too. A Benami transaction involves the transfer or holding of any assets—property or cash—movable or immovable, by any individual, HUF, firm and company or artificial jurisdictional person, where the consideration of the same is provided or paid by some other person, and it is for immediate or future benefit, direct or indirect, of the latter. So, all those who have purchased property in their mother, father or sibling’s name without being a joint shareholder, could face a sentence of seven years in jail. They will also have to pay 25 per cent penalty on the fair market value of the property. The new Act also allows the government to confiscate the property without paying any money to the Benamidar.

There are cases where people had bought agricultural farms and land, even in states where outsiders are not allowed. People also buy in their relatives names. Often, buyers pay money for agricultural land to farmers but do not get it registered it in their own names. All such properties will be treated as Benami transaction. In such cases, the relative or farmer is called ‘Benamidar’ and person making payment is the ‘beneficiary’. The new Act also incriminates Benami transactions that seek to avoid payment of statutory dues or to avoid payment to creditors. Here, the beneficiary owner, the Benamidar, and ‘any other person’ including chartered accountants or advocates, who abets or induces Benami transactions are guilty of the offence. Such activity is punishable with imprisonment ranging between one and seven years.

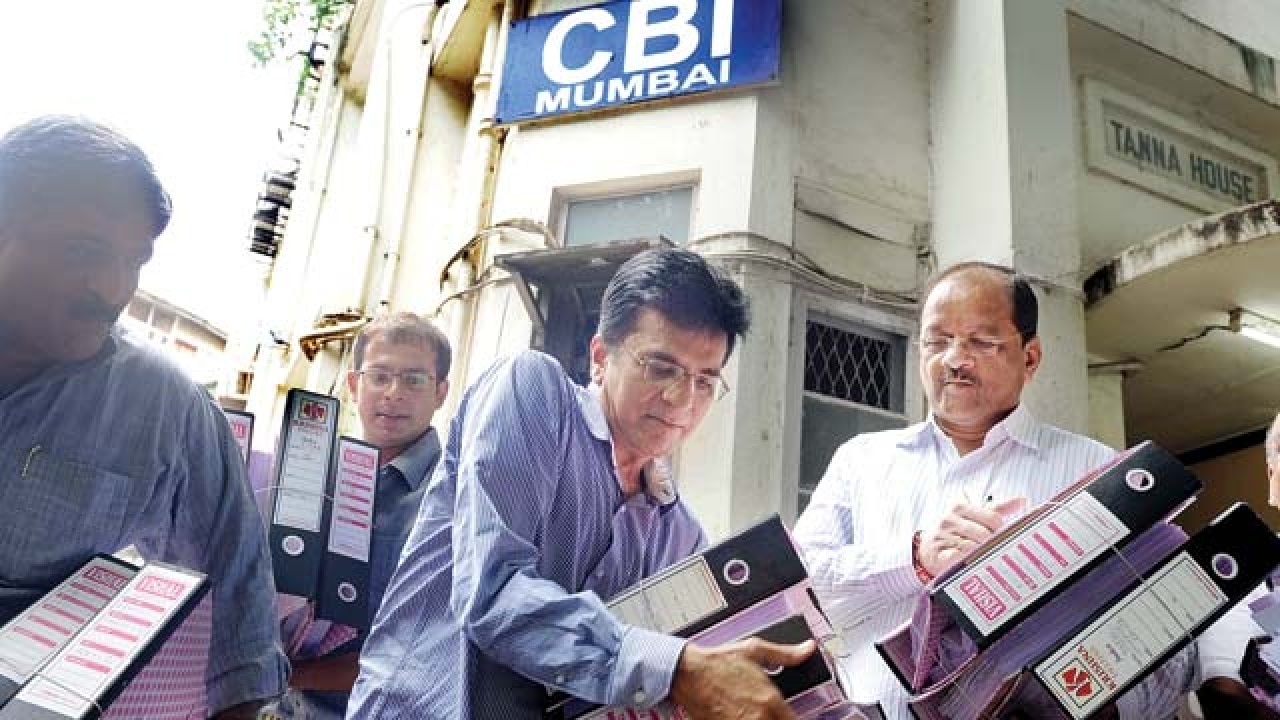

The first opportunity to implement the Benami Act has come with demonetisation, which promised to tackle black money, particularly that stashed in cash. An estimated Rs 15.44 trillion in old notes were demonetised. The tax department has identified 18 lakh people whose cash deposits post-demonetisation do not appear in line with their tax profile. Of these, more than five lakh may face the new Benami law. The I-T department has also found so-called advisers who facilitated these suspicious transactions. But there is an exit route for such people. To avoid legal consequences, they can declare Benami transaction or black money under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojna (PMGKY) by March 31, 2017. In PMGKY, Benami transactors must declare the amount and pay 49.9 per cent tax, and then put another 25 per cent in a four-year interest-free deposit under PMGKY. The remaining money goes to the beneficiary. But with the PMGKY not getting the expected response, a mega-drive against tax evaders could be initiated as soon as state elections are over.