I was travelling from Bengaluru to Delhi, interrupting my winter vacation for a conference. A co-passenger asked, “What is it about? Must be really special if you are foregoing part of your holiday for it.”

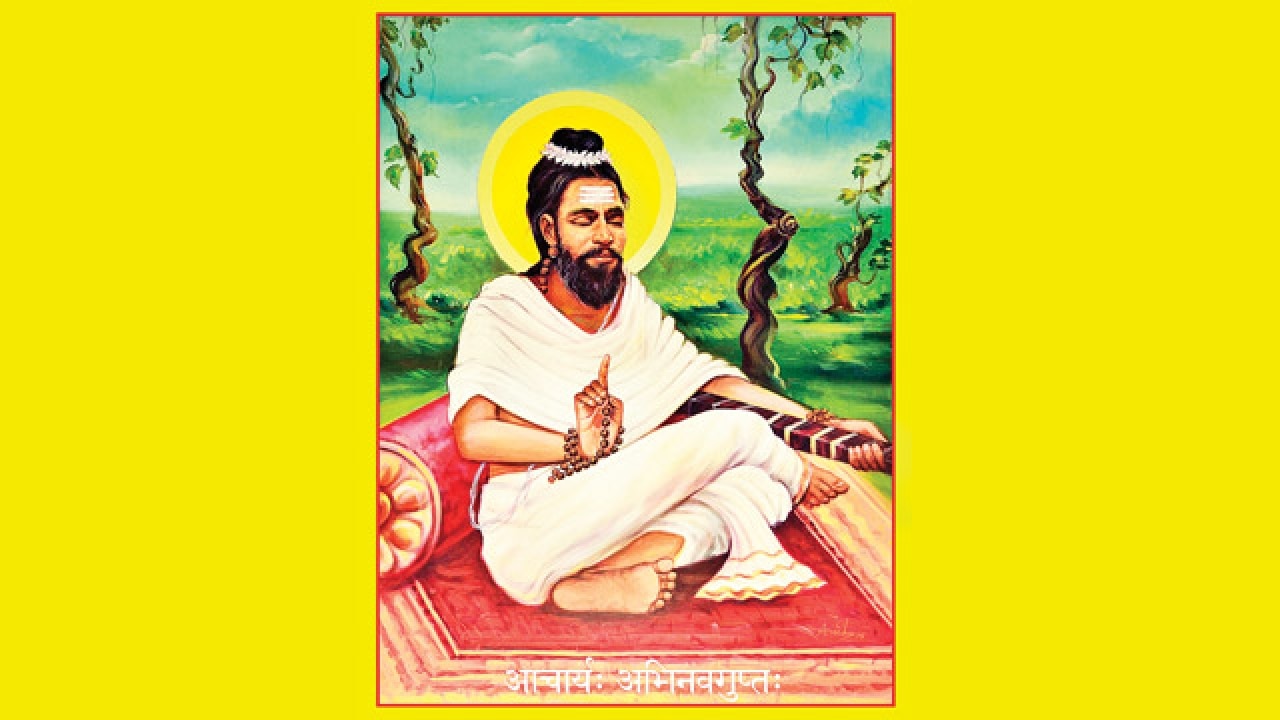

“Yes,” I replied, “It’s on Acharya Abhinavagupta….”

“Acharya who?” My interlocutor asked, slightly taken aback.

“The most important Indian philosopher barring, perhaps, Shankaracharya.”

“Really! Never heard of him.” The person sitting beside me was evidently educated, intelligent, and well to do. But he hadn’t heard of Abhinavagupta (c. 950-1016), even during the on-going millennial celebration of the latter’s life and works.

One fact suddenly became clear. The loss of Kashmir means much more than the loss of territory or power. It is the loss of India’s intellectual and cultural integrity. That is because right up to the Islamic conquest of Kashmir, probably even a couple of centuries after that, Kashmir remained the center of India’s highest attainments in knowledge, philosophy, thought, and culture.

It was the confluence of all the crosscurrents of Indian spirituality, Vedic, Buddhist, Tantric, Yogic, devotional, and philosophical. Later, Islamic mysticism also entered and commingled in this stream. Even today, if there is a missing link between ourselves and our past, it is because the intellectual heritage of Kashmir has not yet been fully recovered or integrated. The result is a puzzling question mark or missing link in our self-understanding and self-confidence.

The great acharyas of our middle centuries Adi Shankara (788-820), Ramanuja (1017-1137), Madhva (1238-1113), Vallabha (1479–1531), and Chaitanya (1486 -1534) are better known all over the sub-continent, their masterworks still recited and remembered. Similarly, the bhakti saint-singers who followed have permeated our consciousness, their compositions sung daily, forming the bedrock of our popular socio-spiritual arrangements, the informal constitution or code of conduct of our country. But Kashmir Shaivism, which refers to a complex network of lineages, doctrines, and practices, still remains little understood and much neglected.

It remained largely left out in the great revival-cum-synthesis of Hindu thought and culture that took place in the nineteenth century, under the aegis of British colonialism. Given the emphasis on comparative philology, it was the Vedic corpus that received the maximum attention of the Orientalists, followed by the Upanishads, the six systems of philosophy, and, thereafter, the epics, Puranas, and Bhakti literature.

It was left to a secondary rung of Indologists, both Euro-American and Indian, gradually to fill in the gaps. Thus, Tantra came seriously to be studied only in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Even now, it remains to be properly integrated into the intellectual history of India, let alone properly understood. This is also true of the so-called heterodox schools, which are mostly studied separately, by adherents and proponents, and often considered separate religions. Actually, none of these intellectual traditions can be considered in isolation of the others; they all emerge from a complex and interactive matrix of evolving Indian knowledge traditions.

Abhinavagupta is so significant because in his astonishing oeuvre of over forty major works, he synthesised and explicated most of the knowledge of his age. Though his compositions are classified as commentaries, they are highly original, innovative, and creative, both in form and technique. He wrote both verse and prose. His magnum opus, Tantraloka, in prose, is a massive and masterly compendium on the philosophy, textual, and ritual traditions of Tantra. It is yet to be properly translated into English and consequently remains largely unknown and unassimilated in the dominant, Anglo-centric world.

Going by Abhinavagupta’s masterful exposition, Kashmir Shaivadarshana, more properly referred to as Trika — Trikashastra or Trikashasana — springs to life with astonishing clarity and cogency. A simplistic way to describe it is in terms of a series of interlocking sets of three: Shiva, Shakti, Anu; Pati, Pasha, Pashu; Nara, Shakti, Shiva; Para, Apara, Parapara; Bheda, Abheda, Bheda-Abehda; and so on. Actually, Trika may also be seen as referring to Siddha, Namaka, and Malini, the three principal Agamas. Or to the three main schools Kula, Krama, and Pratyabhijna. Or to three sources of authority, Nigama (Veda), Agama (Tantra), and Spanda (the doctrine of vibration), that traverses the first two.

Among Abhinavagupta’s most significant works are: Paratrishika Vivarna and Paratrishika Laghuvritti, Pratyabhijna Vimarshini and Pratyabhijna Vivriti, Tantraloka and Tantrasara. Each of these three sets consists respectively of a longer work and shorter summary. He also wrote an original and fascinating commentary on Bhagavad Gita called Gitartha-Samgraha. Some of his compositions, alluded to in his various works, are lost, but so many have, almost miraculously, survive to our times.

As I write these works, there’s a nation-wide outrage over the moral policing and bullying of Dangal star, Zaira Wasim, forced to apologise on social media for being the wrong kind of role model to youngsters. This spurt of continuing narrow-mindedness and intolerance is convincing proof that Kashmir needs Abhinavagupta and Trikadarshana even more than the rest of India, just as Afghanistan needs Panini, its grammarian ancestor, and Pakistan Takshashila, possibly the world’s oldest university. Trikadarshan was the religious and spiritual heritage of Kashmir, lately confined only to the Pandits, with the late Swami Lakshman Joo its last exponent. Now let us hope that like the Nalanda school of Mahayana Buddhism, it spread across the world, even if it has more or less vanished from the land of its origin.

Coming back to Abhinavagupta (c. 950-1016), few in India appreciate that he represents the acme of Indian culture, integrating the best of the religion, ritual, intellect, spirituality, aesthetics, linguistics, and philosophy of his times and leaving an unmatched legacy for future generations. Our eternal gratitude and homage to him for opening so many unprecedented and unmatched ways to know and liberate ourselves from earthly sorrows. What is more, to find our ultimate freedom and never-ending bliss in such self-awareness.

The author is a poet and professor at JNU, New Delhi.