For most people Indian history is Mughal history, ancient history is about the Mauryas. Modern history? British India of course, with the focus on the north, though all the European powers first established their home base in south India. If you drive down the Coromandel coast you will find (as I did), the old offices of the British and French East India companies in Cuddalore and Pondicherry, a Danish fort bang on the seashore in Tranquebar, a Dutch cemetery in Pulicat, a Portuguese flagpole in Nagapattinam. But even the south remains ignorant of its own history, while north Indians see everything south of the Vindhyas as “Madrasi”.

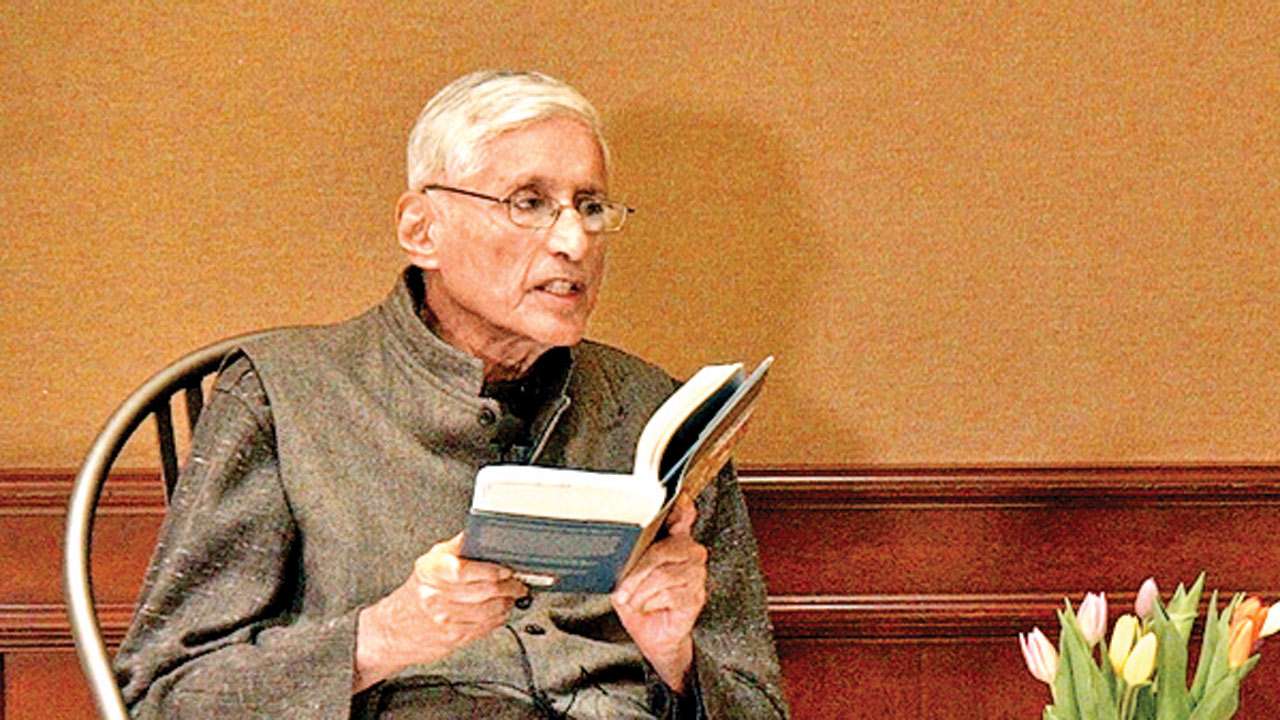

The opportunity to have a conversation with Dr Rajmohan Gandhi about his book “Modern South India” (2018) at the University of Chicago, and for Kalapriya Center’s public event, helped me to learn about the turbulent history of this little-known terrain from the 17th to 20th centuries. The book has events and characters ranging across four regions, their socio-political and geo-historical details, languages and cultures. Events tumble upon one another, characters flit in and out. But there are common threads linking the facts.

Gandhi quotes American scholar Bennet Bronson: “When the British founded a fort at Madras in 1639, India was at the center of an economic and cultural world system, with a quarter of the world’s total manufacturing capacity located within its peninsular boundaries.” Then proceeds to shows how, through four centuries, from being at the head of agricultural production and manufacture, the country sank to impoverishment and colonisation. Why?

Kings and chieftains preferred to feud with their neighbours than unite to fight the invader, asking the invader’s help to capture their neighbours’ territories, until the invader takes over their suzerainty. A basic instinct the British developed into a full-fledged divide-n-rule policy. That is how, though the British saw him as great a threat to their empire as Napoleon, Tipu Sultan (1750-99) was ultimately defeated by Company troops. This was the fate of the freedom-loving chieftains as well – from poligar Kattabomman (Tamil Nadu) to Kerala’s Pazhassi Raja (Kerala) and Rani Chennamma (Karnataka).

Gandhi identifies a crucial moment in the forgotten Battle of Adyar (1746) in Madras. The huge army of the Nawab of Arcot is defeated by a miniscule French force because the French cannon fired six times a minute while theirs could fire only once in fifteen minutes. The discovery that Indian armies were no match for the superior cannons of Europe changed the destinies of nations.

Richly textured by references to writers and literature, the book shows how culture brings insights to the historian. And, against the bitter language politics of today, it is amazing to learn in that in the 1700s and 1800s many were multilingual, fluent not only in Indian languages, but in European tongues as well. Tipu’s brahmin minister Purniah knew kannada, Sanskrit, Persian and English. The “dubash” (translator) was indispensable to the white man, and diarist Anandarangam Pillai, translating for General Dupleix, gives elaborate accounts of French-Tamil interactions. Western soldiers, administrators, missionaries and scholars discovered, preserved, translated and published literary works in many languages, saving our treasures from disappearance. The poet Vemana, a household name in today’s Telugu world, was rescued from obscurity and published by polyglot Charles Philip Brown.

We learn much from Western records. Abbe Dubois remarks, “The arrogance of the Mussalman is based only on the political authority with which he is invested whereas the brahmin’s superiority is inherent in himself… no matter what his condition in life.” British engineer Blakiston writes of vultures accompanying the condemned ring leaders of the Vellore Mutiny (1806) and “hovering over the guns till the final flash, which scattered the fragments of bodies in the air. They caught in their talons many pieces of the quivering flesh.”

Hindu-Muslim alliances and dissensions are an integral part of the history of south India. History shows how Hindu kings trusted their Muslims soldiers and Muslim kings depended on Hindu ministers. In the 17th and 18th centuries discords seem to have been instigated by greed for wealth and power, among men who felt that they belonged to the same land. From the 19th century the divide widens due to fear and hatred of the “Other”.

We note that in the emerging groups of freedom fighters and activists, multiple opinions are expressed freely within the Congress party or in DMK under CN Annadurai’s leadership. The lifetime friendship between anti-Brahmin iconoclast EV Ramasami Naicker and arch Brahmin and Gandhian Rajaji proves that disagreements, however fundamental, are no bar to bonding.

Finally we ask: recounting unspeakable brutalities on all sides through four centuries of socio-political change, does “Modern South India” leave us teetering between disillusionment and hope? Is history a morality play?

I guess the answer has to come from deep within the reader.

The author is a playwright, theatre director, musician and journalist