Research in printing technology is making it possible to custom-build bones, tissues, teeth and pre-operative models of complex body parts.

This April, a cancer survivor in the United Kingdom became the first ever patient to have his face reconstructed using a 3D printed prosthetic. The cancer had left him with a gaping hole on the left of his face, requiring him to be fed through a tube fitted into his stomach. Surgeons restructured his face using old photographs and a mirror image of the existing portion, then printed the silicon prosthetic.

From fashion to aerospace engineering, 3D printing, also known as Additive Manufacturing, is increasingly used in multiple industries with researchers also finding exciting medical applications for 3D printing in orthopaedics, dentistry and regeneration of organs. Closer home too, laboratories and classrooms are opening up to the medical possibilities offered by 3D printing.

Dr Kartik Bhanushali, director of Navi Mumbai’s Dr DY Patil Dental College, has 100 students learning to use Computer Aided Design (CAD) and 3D printing as part of their course. “We are also designing a course structure that we plan to get certified and thrown open to 300 dental colleges across the country. It is the future,” says Bhanushali. In his clinic, he uses 3D printing technology to prepare temporary ceramic crowns to cap patients’ problematic teeth. Permanent crowns built using 3D printing are some years away. The heavy work is done by grinders. The load-bearing permanent teeth need a metal composite but these aren’t compatible with the printer just yet,” says Bhanushali.

3D printing, which has been around since the late ’80s, involves sending a CAD file sent to a special printer that prints a three-dimensional object, one fine layer at a time. A layer can be as fine as one micron or 0.001mm. The materials used vary from ceramics, plastics to metals.

In 1986, US inventor Charles Hull created the first machine that produced 3-dimensional objects using a printer connected to a computer. Hull’s technology used liquid resin to build the design layer by layer. An ultraviolet light was used to harden the layers fusing them to each other. The printers were expensive and had limitations, hence their use was restricted to industries that used it for prototyping. But advances in the technology have since increased the type of materials used and the efficiency (thinner the layer, more accurate the design) opening the area to more research and applications.

It’s the way forward in orthopaedics

Only in April, Ayishwariya Menon, clinical team manager at Materialise, a 3D printing research and development firm in Malaysia, was in Mumbai to speak to medical practitioners about adopting 3D printing. In orthopaedics, the technology can be used to create customised anatomical models and patient specific instruments based on the patient’s anatomy, taken from a CT scan, which then help plan and carry out a surgery.

“This reduces the guess work for a surgeon in a complicated operation since he or she is able to recreate the exact conditions of the bone beforehand. Surgeons can also prepare jigs, instruments that guide a bone drill, based on the model that will fit real bone accurately,” explains Guruprasad Rao, CEO of Imaginarium, a 3D manufacturing unit in Mumbai. His unit accepts outsourced 3D printing jobs from surgeons and hospitals as well as from fashion and other industries.

The printer can also create implants be it tooth or the mandible (jaw bone). Since the printed implant will be in contact with the body for a long time, the material is required to be bio-compatible so that the body tissues in contact with it do not reject the foreign object or cause an infection. For this purpose the US government-run Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved certain materials which fit the bill. This includes ceramics, polymers and metals like titanium.

“Everyone is unique. The technology allows patient-specific treatments, implants and devices. Patient-specific healthcare will grow very quickly because of this,” says Menon. Materialise has also managed to print a titanium lower jaw bone for a patient.

Traditionally reconstructive jaw bone surgery is a carried out using titanium screws and plates.

The 3D printed version allows for more accurate dimensions reducing the time spent in the operation theatre and post-operative recovery.

New research holds promise too. At Washington State University, researchers Dr Susmita Bose and Dr Amit Bandyopadhyay are putting the finishing touches on a system to use a ceramic 3D printed scaffold that will form the support on which bone tissue will grow in patients. The scaffold is made of a porous material that dissolves in the body over time. “Almost 70 per cent of our bones are made up of calcium phosphate. This way, we can control the geometry of the printed bone and the chemical composition. Metallic implants can be used for load-bearing bones,” says Bose, who sees great potential in treating medical trauma cases this way.

The future is here

Dr Narinder Mehra, head of the department of Transplant Immunology & Immunogenetics at AIIMS, New Delhi, says the technology has a long way to go in India but the potential is vast.

“Currently the short supply of kidneys in organ banks is an increasing obstacle. While research is still in its trial phase in Japan, the possibility of bio-printing or printing of live tissue reducing this gap promises that the technology has good scope in transplantation.”

According to Menon, this technology will take at least 20 years to reach hospitals.

Researchers believe this is just the tip of the iceberg. Surgeon Anthony Atala, director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, recently demonstrated how 3D printing could someday soon solve the organ-donor problem. His research, which is still in the early stages of testing uses a 3D printer to print thin sheets of living tissue taken. This tissue is taken from patients and made to grow and reconstruct on a scaffold of cells in the form of a kidney. This will help grow a functional kidney for that specific patient.

![submenu-img]() IND vs SL, 1st T20I: Predicted playing XIs, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

IND vs SL, 1st T20I: Predicted playing XIs, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Women's Asia Cup 2024: India beat Bangladesh by 10 wickets to reach ninth successive final

Women's Asia Cup 2024: India beat Bangladesh by 10 wickets to reach ninth successive final![submenu-img]() Apple reduces prices of iPhones across models, iPhones 13, 14 and 15 will be cheaper by Rs...

Apple reduces prices of iPhones across models, iPhones 13, 14 and 15 will be cheaper by Rs...![submenu-img]() 'Elon Musk treated me badly for...,' says Tesla chief's daughter Vivian Jenna Wilson

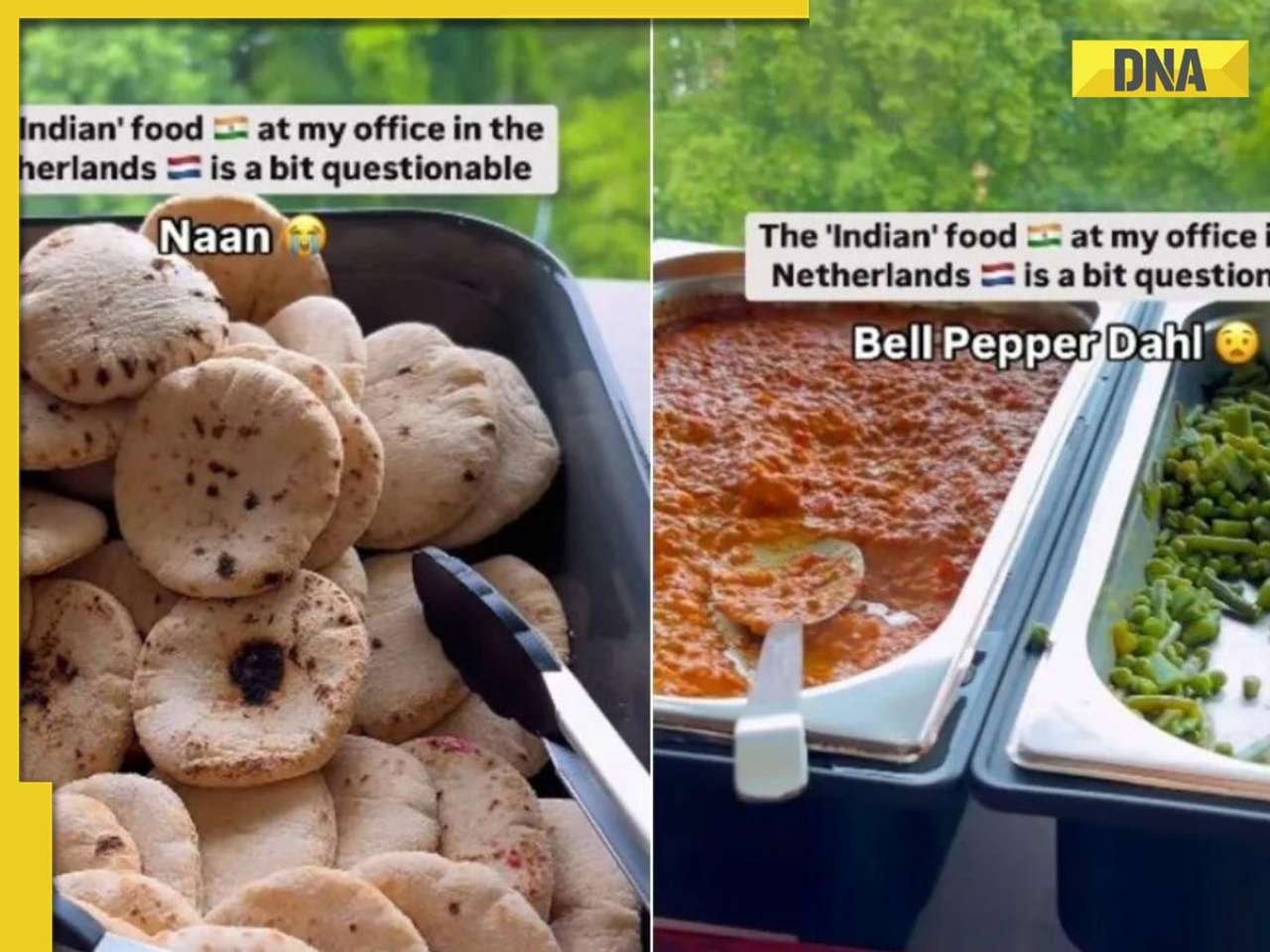

'Elon Musk treated me badly for...,' says Tesla chief's daughter Vivian Jenna Wilson![submenu-img]() Watch video: 'Questionable' Indian food served to employees in Dutch office; Internet reacts

Watch video: 'Questionable' Indian food served to employees in Dutch office; Internet reacts![submenu-img]() Meet woman, a doctor who cleared UPSC exam to become IAS officer, resigned after 7 years due to...

Meet woman, a doctor who cleared UPSC exam to become IAS officer, resigned after 7 years due to...![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer, one of India's most educated men, who earned 20 degrees, gold medals in...

Meet IAS officer, one of India's most educated men, who earned 20 degrees, gold medals in...![submenu-img]() Meet Maths genius, who worked with IIT, NASA, went missing suddenly, was found after years..

Meet Maths genius, who worked with IIT, NASA, went missing suddenly, was found after years..![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who fled to Delhi from Pakistan, worked at two IITs, awarded India’s top science award for…

Meet Indian genius who fled to Delhi from Pakistan, worked at two IITs, awarded India’s top science award for…![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam after accident, underwent 14 surgeries, still became IAS officer, she is...

Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam after accident, underwent 14 surgeries, still became IAS officer, she is...![submenu-img]() 5 Men Rape Australian Woman In Paris Just Days Ahead Of Olympic | Paris Olympics 2024

5 Men Rape Australian Woman In Paris Just Days Ahead Of Olympic | Paris Olympics 2024![submenu-img]() US Elections: 'I Know Trump's Type', Says Kamala Harris As She Launches Election Campaign

US Elections: 'I Know Trump's Type', Says Kamala Harris As She Launches Election Campaign![submenu-img]() Breaking! Nepal Plane Crash: Saurya Airlines Flight With 19 On Board Crashes In Kathmandu

Breaking! Nepal Plane Crash: Saurya Airlines Flight With 19 On Board Crashes In Kathmandu![submenu-img]() J&K Encounter: Search Operation By Indian Army, Police Continue, 1 Terrorist Neutralised In Kupwara

J&K Encounter: Search Operation By Indian Army, Police Continue, 1 Terrorist Neutralised In Kupwara![submenu-img]() Breaking! Nepal Plane Crash: Saurya Airlines Flight With 19 On Board Crashes In Kathmandu

Breaking! Nepal Plane Crash: Saurya Airlines Flight With 19 On Board Crashes In Kathmandu![submenu-img]() NASA images: 7 mesmerising images of space will make you fall in love with astronomy

NASA images: 7 mesmerising images of space will make you fall in love with astronomy![submenu-img]() 8 athletes with most Olympic medals

8 athletes with most Olympic medals![submenu-img]() In pics: Step inside Jalsa, Amitabh Bachchan, Jaya Bachchan's Rs 120 crore mansion with gym, jacuzzi, aesthetic decor

In pics: Step inside Jalsa, Amitabh Bachchan, Jaya Bachchan's Rs 120 crore mansion with gym, jacuzzi, aesthetic decor![submenu-img]() Remember Paul Blackthorne, Lagaan's Captain Russell? Quit films, did side roles in Hollywood, looks unrecognisable now

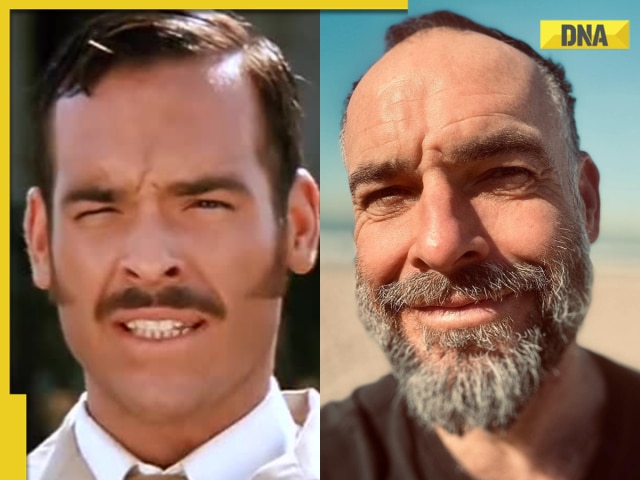

Remember Paul Blackthorne, Lagaan's Captain Russell? Quit films, did side roles in Hollywood, looks unrecognisable now![submenu-img]() This actor was called next superstar, bigger than Amitabh, Vinod Khanna, then lost stardom, was arrested for wife's...

This actor was called next superstar, bigger than Amitabh, Vinod Khanna, then lost stardom, was arrested for wife's...![submenu-img]() Meet man, tribal who tipped off Army about Pakistani intruders in Kargil, awaits relief from govt even after...

Meet man, tribal who tipped off Army about Pakistani intruders in Kargil, awaits relief from govt even after...![submenu-img]() Puja Khedkar case latest update: Shocking details about her parents Manorama Khedkar, Dilip Khedkar revealed

Puja Khedkar case latest update: Shocking details about her parents Manorama Khedkar, Dilip Khedkar revealed![submenu-img]() Kargil Vijay Diwas Live Updates: PM Modi visits Dras to mark 25th anniversary of Kargil Vijay Diwas

Kargil Vijay Diwas Live Updates: PM Modi visits Dras to mark 25th anniversary of Kargil Vijay Diwas![submenu-img]() Big rejig in BJP: New state chief for Bihar and Rajasthan named

Big rejig in BJP: New state chief for Bihar and Rajasthan named![submenu-img]() Mumbai rains: Schools, colleges to operate normally today, BMC urges citizens to...

Mumbai rains: Schools, colleges to operate normally today, BMC urges citizens to...![submenu-img]() DRDO fortifies India's skies: Phase II ballistic missile defence trial successful

DRDO fortifies India's skies: Phase II ballistic missile defence trial successful![submenu-img]() Gaza Conflict Spurs Unlikely Partners: Hamas, Fatah factions sign truce in Beijing

Gaza Conflict Spurs Unlikely Partners: Hamas, Fatah factions sign truce in Beijing![submenu-img]() Crackdowns and Crisis of Legitimacy: What lies beyond Bangladesh's apex court scaling down job quotas

Crackdowns and Crisis of Legitimacy: What lies beyond Bangladesh's apex court scaling down job quotas![submenu-img]() Area 51: Alien testing ground or enigmatic US military base?

Area 51: Alien testing ground or enigmatic US military base?![submenu-img]() Transforming India's Aerospace Industry: Budget 2024 and Beyond

Transforming India's Aerospace Industry: Budget 2024 and Beyond![submenu-img]() Chalti Rahe Zindagi review: Siddhant Kapoor's relatable but boring lockdown drama can be skipped

Chalti Rahe Zindagi review: Siddhant Kapoor's relatable but boring lockdown drama can be skipped ![submenu-img]() 'This is nothing but...': Pahlaj Nihalani on CBFC's delay in censor certification of John Abraham's Vedaa

'This is nothing but...': Pahlaj Nihalani on CBFC's delay in censor certification of John Abraham's Vedaa ![submenu-img]() Does Janhvi Kapoor pay for social media praise, positive comments? Actress reacts, 'itna budget...'

Does Janhvi Kapoor pay for social media praise, positive comments? Actress reacts, 'itna budget...'![submenu-img]() Parineeti Chopra's cryptic post about 'throwing toxic people out of life' scares fans: 'Stop living for...'

Parineeti Chopra's cryptic post about 'throwing toxic people out of life' scares fans: 'Stop living for...'![submenu-img]() Highest grossing animated film ever has earned Rs 12200 crore; beat The Lion King, Toy Story, Frozen, Minions, Shrek

Highest grossing animated film ever has earned Rs 12200 crore; beat The Lion King, Toy Story, Frozen, Minions, Shrek![submenu-img]() Watch video: 'Questionable' Indian food served to employees in Dutch office; Internet reacts

Watch video: 'Questionable' Indian food served to employees in Dutch office; Internet reacts![submenu-img]() This small nation is most important country in world, plays huge role in shaping geopolitics, it is...

This small nation is most important country in world, plays huge role in shaping geopolitics, it is...![submenu-img]() El Mayo in US custody: Who is Mexican drug lord Ismael Zambada, Sinaloa cartel leader arrested with El Chapo's son?

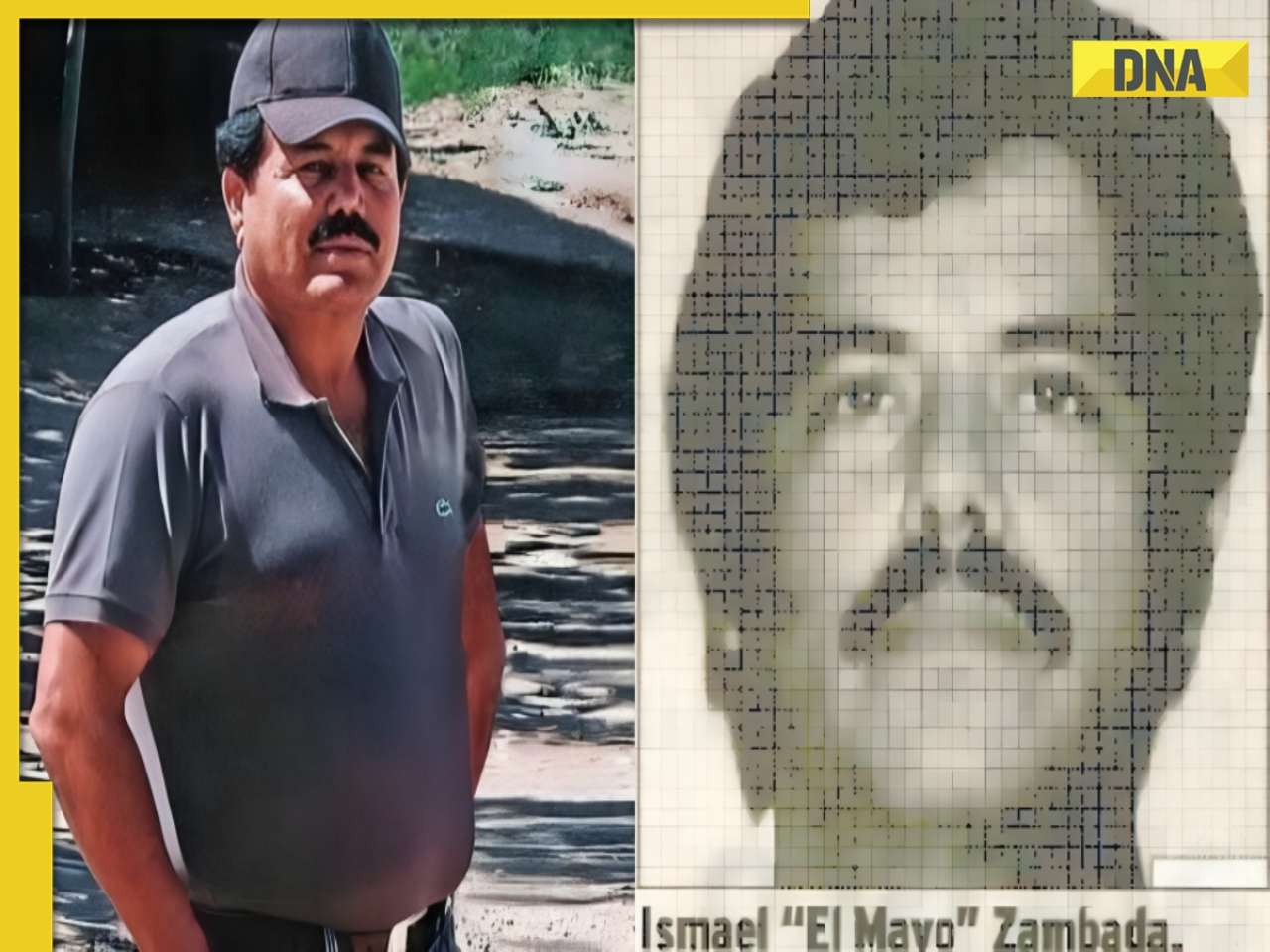

El Mayo in US custody: Who is Mexican drug lord Ismael Zambada, Sinaloa cartel leader arrested with El Chapo's son?![submenu-img]() Viral video: 15-foot python attacks and nearly swallows Jabalpur man, here's how locals save him, watch

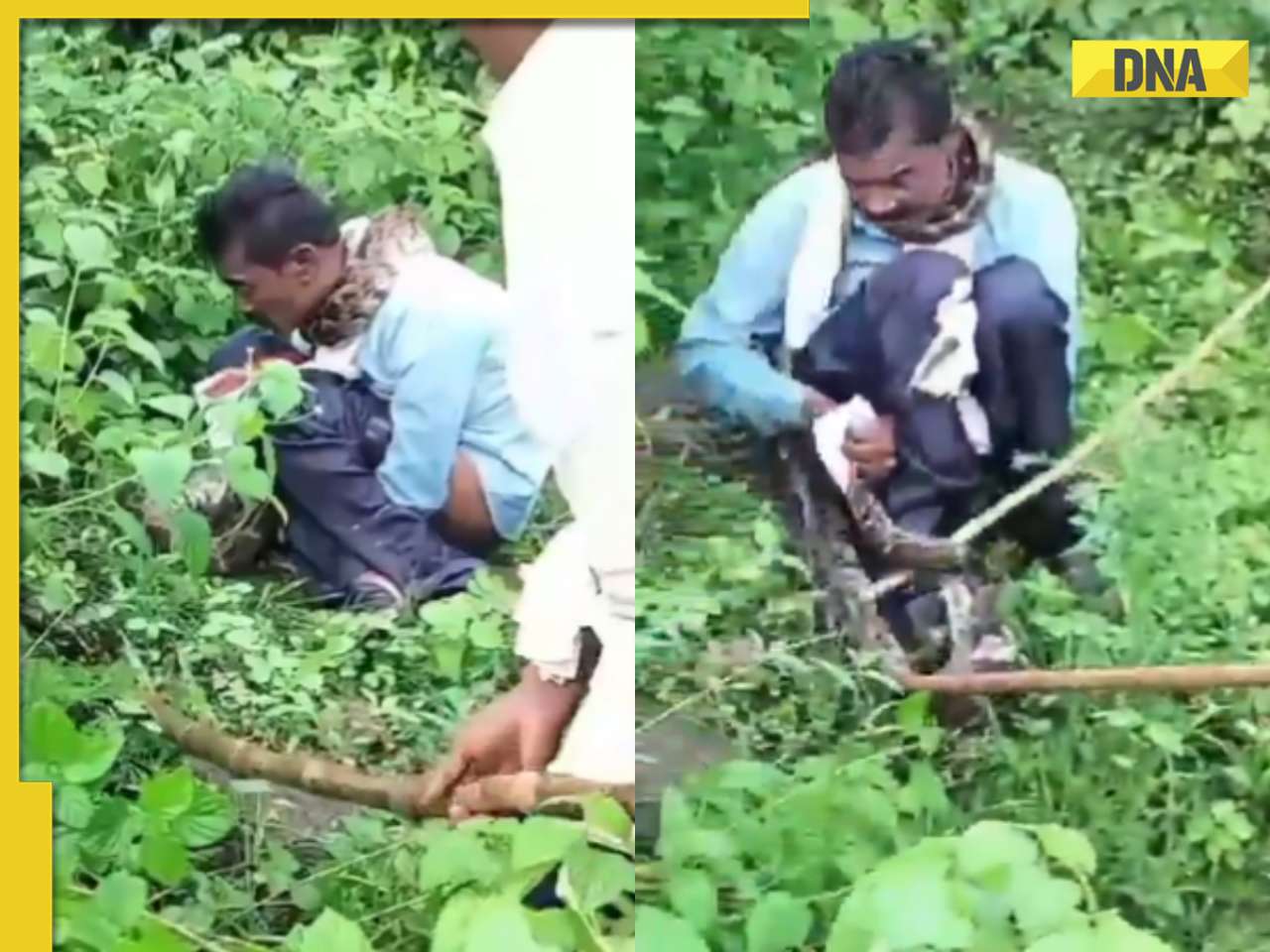

Viral video: 15-foot python attacks and nearly swallows Jabalpur man, here's how locals save him, watch![submenu-img]() 'Anant knows everything': Akash Ambani, Isha Ambani tell Amitabh Bachchan as…

'Anant knows everything': Akash Ambani, Isha Ambani tell Amitabh Bachchan as…

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)