Was Kartikeya older or Ganesh? Was he really more powerful than Shiva himself? And who was Ashokasundari? Roshni Nair talks to historians, mythologists and other scholars to put together the story of a family of gods

In 1972, Bombay’s Subramania Samaj trust purchased a 2,300sq. yard plot in Chedda Nagar, Chembur. With that, the organisation kick-started a mission to build a Murugan temple that took eight years to bear fruit.

“Back home, structures like this are usually built on hillocks. But where could one find a hillock in Bombay?” laughs Subramania Samaj secretary PS Subramaniyan. “So our architects devised a novel solution.”

This solution was the construction of a three-level complex whose heart was on an elevated site – a ‘manmade hill’. Eight hundred tonnes of granite were chiseled by Mahabalipuram sculptors. That work itself took six years. “Another challenge was to adhere to bhoosparsham (earthly contact),” says Subramaniyan. “This was achieved with raised sand pits from the ground to the elevated shrine.”

And so, in 1980, Thiruchembur Thirumurugan Temple, the first Murugan temple in Mumbai, came to be.

For Tamilians, no deity is as hallowed as Murugan or Kartikeya, the Hindu god of war and the God of the Hills. Brother Ganesh may be popular elsewhere, but Tamil katavul Murugan’s evolution story is no less fascinating.

In north India, the oft-recounted ‘race around the world’ tale – where Ganesh circumambulates parents Shiva and Parvati while Kartikeya goes around the world – marks the wane of Kartikeya from popular lore. In this version, he’s miffed with the outcome of the contest with his brother (over a mango, offered by wily Narada) and takes a vow of celibacy, leaving Mount Kailash for the Palni Hills of south India.

“Murugan is distinct from the Kumara of north and east India. In the south, he has two wives, Devasena and Valli. He was probably an ancient mountain god associated with Mars, virility and war before the arrival of Brahminism, as indicated by Tamil Sangam literature,” says author and mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik. “Then Murugan was adopted as the son of Shiva. But in many stories, he knows secrets known not even to Shiva, making him more powerful. Clearly, he is a product of the merging of many communities over centuries.”

Origins

As Pattanaik says, Murugan is dissimilar from the Puranic Kartikeya, at least in early stages. He’s described in ancient Sangam works, such as the Tolkappiyam, as Ceyyavan or ‘the red one’.

But what’s fascinating is the likelihood of an origin story dating centuries before Dravidian literature. In his 1999 paper 'Murukan in the Indus Script', Iravatham Mahadevan, one of India's foremost scholars on the Indus Valley civilisation, indicated that a primitive Muruku – a red-hued, demon-like war god – may have been worshipped. “…virtually all the Tamil inscriptions and iconographic motifs have been heavily influenced by the Sanskritic traditions of Skanda-Karttikeya-Kumara and have very little in common,” wrote Mahadevan. “Even the meaning of his name has undergone a radical transformation from muruku, 'the demon or destroyer' to Murukan, 'the beautiful one’.”

That said, there’s no consensus on Mahadevan’s theory, feels Dr R. Mahalakshmi, associate professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University’s (JNU) Centre for Historical Studies (CHS). But she does talk about Puranic influence on Sangam works. An example is the recasting of local mother goddess Kotravai into Parvati. “Kotravai was the goddess of war and victory. She got sidelined, but her son Murugan is venerated. There’s no Ganesh in Sangam tradition. He and Shiva appear in later texts.”

Such regional variances also extend to which brother is older. “In north Indian Pahari paintings, Ganesh is visualised as the younger son. In south Indian imagery, Ganesh is older and celibate while Kartikeya is a virile romantic child-god, almost like Krishna,” Pattanaik says. And in north India itself, there are different versions of the story about the Ganesh-Kartikeya race. In some accounts, the contest isn’t over a mango, but over who would get to wed first.

Since Kartikeya is considered a brahmachari by most, women are expected to not worship him, except on Kartik Poornima. “The oldest heritage spot in Pune is a Kartikeya temple on Parvati Hill, where female worshippers can’t go beyond a point,” says Subramaniyan. “There's even a belief that unmarried people shouldn't worship Kartikeya. But in the south, women worship him year-round.”

Ungodly progeny

In 2012, teleserial Devon Ke Dev...Mahadev got people talking when it introduced a character called Ashokasundari – the daughter of Shiva-Parvati. Kartikeya may be less popular than Ganesh, but even then, both have places of prestige in the Hindu pantheon. Not so their virtually-unknown sister. Save for the Padma Purana, Ashokasundari isn’t mentioned in major Hindu works, says Dr. Madhavi Narsalay, associate professor at the Department of Sanskrit, University of Mumbai. “The story goes that Parvati was lonely after Ganesh and Kartikeya left Mount Kailash, so she requested Shiva to take her to the celestial garden Nandanvan. There, she was gifted a baby girl from the kalpavriksha tree. ‘Ashoka’ literally means ‘lack of sadness’ – denoting the role Ashokasundari played in Parvati’s life,” she says.

The Ashokasundari arc was helmed into Devon Ke Dev...Mahadev largely in part due to Devdutt Pattanaik, who was one of the show’s consultants. “We didn’t want to endorse patriarchy and show Shiva preferring only male children,” he explains.

Ashokasundari isn’t the only forgotten Shiva-Parvati offspring. At the opposite end of the spectrum to Ganesh and Kartikeya are demon sons Jalandhara and Andhaka. While Jalandhara originated from Shiva’s third eye, Andhaka was created from Parvati’s sweat. Both were adopted by Varuna (the god of water) and Asura king Hiranyaksha respectively. In her working thesis for JNU, 'Siva's Kutumba: Literary and Iconographic Representations in Northern India', Neha Singh notes that both demons rebelled against Shiva and tried attaining Parvati sexually – which not only led to their doom, but also made them unworthy of worship.

Interestingly, no Shiva-Parvati offspring is biological. While Parvati created Ganesh out of clay, Kartikeya was borne of Shiva’s semen. Of course, as in most Hindu mythology, such birth stories have several variations. Regardless, Dr. Madhavi Narsalay points to one family template here anyone can identify with:

“The entire family has vahanas (mounts) that are ‘enemies’ of one another. Parvati or Durga has the lion, Shiva has Nandi (cow), Ganesh sits on a rat, and Kartikeya, on a peacock. Then there’s the snake around Shiva’s neck. These could indicate conflicting energies staying together as family.”

Narsalay adds that few accounts of Sanskritic poetic imagination even joke about Shiva consuming poison because he was tired of family feuds – including the alleged sibling rivalry between Ganesha and Murugan.

Whatever be the case, there’s comfort in knowing even godly families aren't immune to dysfunctionality. And this is what makes the Shiva-Parvati family endearing and identifiable.

Addendum

It's not just Shiva and Parvati's three children that find themselves edged to Hindu mythology's dark corners. There's also the curious case of Vinayaki, whose other monikers include 'Vighneshwari' and 'Stri Ganesha' – the female Ganesha.

But Vinayaki is no consort, sibling, or any familial relation of Ganpati's. She is one of Hinduism's 64 yoginis, a representative of the sacred feminine (Shakti). Temples to her and other yoginis are scattered across India, from Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh to Orissa and Kerala – though many are in a decrepit state.

In his 1975 essay 'The Enigma of Vinayaki' for the Artibus Asiae journal, historian and anthropologist Balaji Mundkur mentioned Shilparatna, a 16th century text from Kerala on the south Indian performing arts. This text (as well as the much older Matsya Purana), he said, referred to a female elephant-headed deity with 'swelling breasts and feminine hips'. “In contrast to the immense popularity of the images of Ganesa, she is not often represented by an icon, not even in human form,” Mundkur wrote. One of the best-preserved idols of Vinayaki, he added, is in Chitrapur Saraswat Math in Shirali, Karnataka. “It is the first and only metal icon of the goddess... intact except for minor damage... It would not seem far-fetched to believe that the icon represents a Tantric cult goddess, undoubtedly a sakti venerated by one of the sects whose popularity was high between the seventh and twelfth centuries AD.”

Tantric and Shakti traditions, whose reputations are often either misunderstood or besmirched, have texts that are regarded at par with Vedic literature, says Mumbai University's Dr. Madhavi Narsalay. And their influence seemed to have seeped into literature like the Ganesha Kosha, which too mentions Vinayaki.

“Since yoginis were the manifestation of female energy, Vinayaki is the feminine energy of Vinayak (Ganesh). There’s also a lore about Lakshmi becoming Vinayaki after affixing the head of an elephant onto herself.”

But this version, Narsalay stresses, has no literary source.

And so, the tale of Vinayaki remains in the shadows.

![submenu-img]() IND vs SL, 1st T20I: Predicted playing XIs, live streaming details, weather and pitch report

IND vs SL, 1st T20I: Predicted playing XIs, live streaming details, weather and pitch report![submenu-img]() Women's Asia Cup 2024: India beat Bangladesh by 10 wickets to reach ninth successive final

Women's Asia Cup 2024: India beat Bangladesh by 10 wickets to reach ninth successive final![submenu-img]() Apple reduces prices of iPhones across models, iPhones 13, 14 and 15 will be cheaper by Rs...

Apple reduces prices of iPhones across models, iPhones 13, 14 and 15 will be cheaper by Rs...![submenu-img]() 'Elon Musk treated me badly for...,' says Tesla chief's daughter Vivian Jenna Wilson

'Elon Musk treated me badly for...,' says Tesla chief's daughter Vivian Jenna Wilson![submenu-img]() Watch video: 'Questionable' Indian food served to employees in Dutch office; Internet reacts

Watch video: 'Questionable' Indian food served to employees in Dutch office; Internet reacts![submenu-img]() Meet woman, a doctor who cleared UPSC exam to become IAS officer, resigned after 7 years due to...

Meet woman, a doctor who cleared UPSC exam to become IAS officer, resigned after 7 years due to...![submenu-img]() Meet IAS officer, one of India's most educated men, who earned 20 degrees, gold medals in...

Meet IAS officer, one of India's most educated men, who earned 20 degrees, gold medals in...![submenu-img]() Meet Maths genius, who worked with IIT, NASA, went missing suddenly, was found after years..

Meet Maths genius, who worked with IIT, NASA, went missing suddenly, was found after years..![submenu-img]() Meet Indian genius who fled to Delhi from Pakistan, worked at two IITs, awarded India’s top science award for…

Meet Indian genius who fled to Delhi from Pakistan, worked at two IITs, awarded India’s top science award for…![submenu-img]() Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam after accident, underwent 14 surgeries, still became IAS officer, she is...

Meet woman who cracked UPSC exam after accident, underwent 14 surgeries, still became IAS officer, she is...![submenu-img]() 5 Men Rape Australian Woman In Paris Just Days Ahead Of Olympic | Paris Olympics 2024

5 Men Rape Australian Woman In Paris Just Days Ahead Of Olympic | Paris Olympics 2024![submenu-img]() US Elections: 'I Know Trump's Type', Says Kamala Harris As She Launches Election Campaign

US Elections: 'I Know Trump's Type', Says Kamala Harris As She Launches Election Campaign![submenu-img]() Breaking! Nepal Plane Crash: Saurya Airlines Flight With 19 On Board Crashes In Kathmandu

Breaking! Nepal Plane Crash: Saurya Airlines Flight With 19 On Board Crashes In Kathmandu![submenu-img]() J&K Encounter: Search Operation By Indian Army, Police Continue, 1 Terrorist Neutralised In Kupwara

J&K Encounter: Search Operation By Indian Army, Police Continue, 1 Terrorist Neutralised In Kupwara![submenu-img]() Breaking! Nepal Plane Crash: Saurya Airlines Flight With 19 On Board Crashes In Kathmandu

Breaking! Nepal Plane Crash: Saurya Airlines Flight With 19 On Board Crashes In Kathmandu![submenu-img]() NASA images: 7 mesmerising images of space will make you fall in love with astronomy

NASA images: 7 mesmerising images of space will make you fall in love with astronomy![submenu-img]() 8 athletes with most Olympic medals

8 athletes with most Olympic medals![submenu-img]() In pics: Step inside Jalsa, Amitabh Bachchan, Jaya Bachchan's Rs 120 crore mansion with gym, jacuzzi, aesthetic decor

In pics: Step inside Jalsa, Amitabh Bachchan, Jaya Bachchan's Rs 120 crore mansion with gym, jacuzzi, aesthetic decor![submenu-img]() Remember Paul Blackthorne, Lagaan's Captain Russell? Quit films, did side roles in Hollywood, looks unrecognisable now

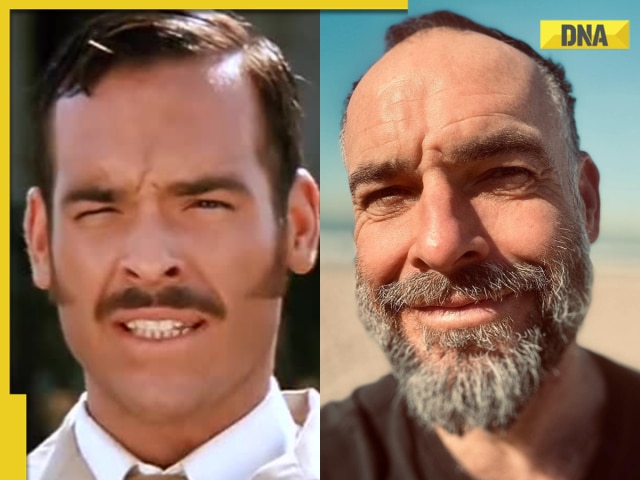

Remember Paul Blackthorne, Lagaan's Captain Russell? Quit films, did side roles in Hollywood, looks unrecognisable now![submenu-img]() This actor was called next superstar, bigger than Amitabh, Vinod Khanna, then lost stardom, was arrested for wife's...

This actor was called next superstar, bigger than Amitabh, Vinod Khanna, then lost stardom, was arrested for wife's...![submenu-img]() Meet man, tribal who tipped off Army about Pakistani intruders in Kargil, awaits relief from govt even after...

Meet man, tribal who tipped off Army about Pakistani intruders in Kargil, awaits relief from govt even after...![submenu-img]() Puja Khedkar case latest update: Shocking details about her parents Manorama Khedkar, Dilip Khedkar revealed

Puja Khedkar case latest update: Shocking details about her parents Manorama Khedkar, Dilip Khedkar revealed![submenu-img]() Kargil Vijay Diwas Live Updates: PM Modi visits Dras to mark 25th anniversary of Kargil Vijay Diwas

Kargil Vijay Diwas Live Updates: PM Modi visits Dras to mark 25th anniversary of Kargil Vijay Diwas![submenu-img]() Big rejig in BJP: New state chief for Bihar and Rajasthan named

Big rejig in BJP: New state chief for Bihar and Rajasthan named![submenu-img]() Mumbai rains: Schools, colleges to operate normally today, BMC urges citizens to...

Mumbai rains: Schools, colleges to operate normally today, BMC urges citizens to...![submenu-img]() DRDO fortifies India's skies: Phase II ballistic missile defence trial successful

DRDO fortifies India's skies: Phase II ballistic missile defence trial successful![submenu-img]() Gaza Conflict Spurs Unlikely Partners: Hamas, Fatah factions sign truce in Beijing

Gaza Conflict Spurs Unlikely Partners: Hamas, Fatah factions sign truce in Beijing![submenu-img]() Crackdowns and Crisis of Legitimacy: What lies beyond Bangladesh's apex court scaling down job quotas

Crackdowns and Crisis of Legitimacy: What lies beyond Bangladesh's apex court scaling down job quotas![submenu-img]() Area 51: Alien testing ground or enigmatic US military base?

Area 51: Alien testing ground or enigmatic US military base?![submenu-img]() Transforming India's Aerospace Industry: Budget 2024 and Beyond

Transforming India's Aerospace Industry: Budget 2024 and Beyond![submenu-img]() Chalti Rahe Zindagi review: Siddhant Kapoor's relatable but boring lockdown drama can be skipped

Chalti Rahe Zindagi review: Siddhant Kapoor's relatable but boring lockdown drama can be skipped ![submenu-img]() 'This is nothing but...': Pahlaj Nihalani on CBFC's delay in censor certification of John Abraham's Vedaa

'This is nothing but...': Pahlaj Nihalani on CBFC's delay in censor certification of John Abraham's Vedaa ![submenu-img]() Does Janhvi Kapoor pay for social media praise, positive comments? Actress reacts, 'itna budget...'

Does Janhvi Kapoor pay for social media praise, positive comments? Actress reacts, 'itna budget...'![submenu-img]() Parineeti Chopra's cryptic post about 'throwing toxic people out of life' scares fans: 'Stop living for...'

Parineeti Chopra's cryptic post about 'throwing toxic people out of life' scares fans: 'Stop living for...'![submenu-img]() Highest grossing animated film ever has earned Rs 12200 crore; beat The Lion King, Toy Story, Frozen, Minions, Shrek

Highest grossing animated film ever has earned Rs 12200 crore; beat The Lion King, Toy Story, Frozen, Minions, Shrek![submenu-img]() Watch video: 'Questionable' Indian food served to employees in Dutch office; Internet reacts

Watch video: 'Questionable' Indian food served to employees in Dutch office; Internet reacts![submenu-img]() This small nation is most important country in world, plays huge role in shaping geopolitics, it is...

This small nation is most important country in world, plays huge role in shaping geopolitics, it is...![submenu-img]() El Mayo in US custody: Who is Mexican drug lord Ismael Zambada, Sinaloa cartel leader arrested with El Chapo's son?

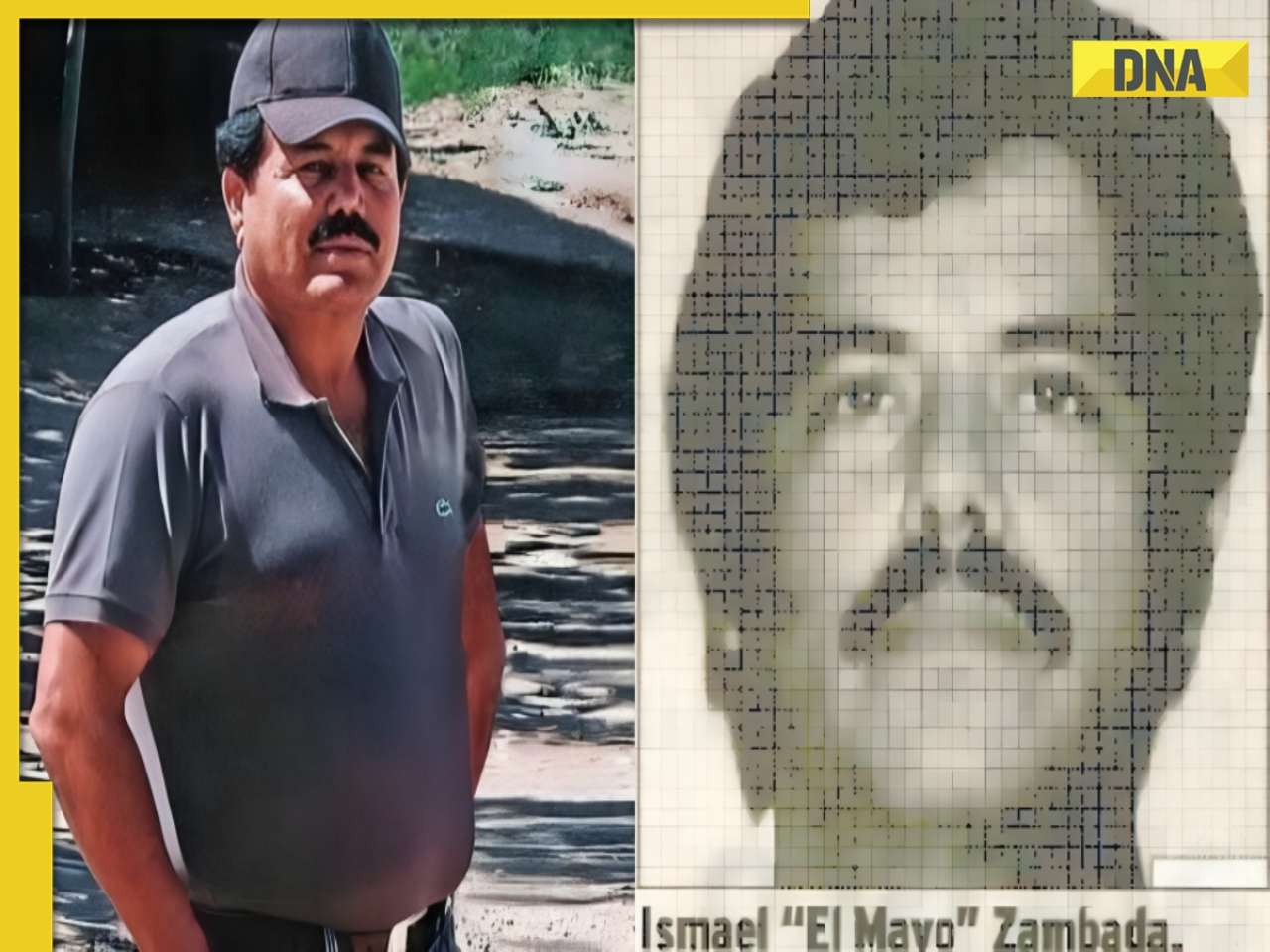

El Mayo in US custody: Who is Mexican drug lord Ismael Zambada, Sinaloa cartel leader arrested with El Chapo's son?![submenu-img]() Viral video: 15-foot python attacks and nearly swallows Jabalpur man, here's how locals save him, watch

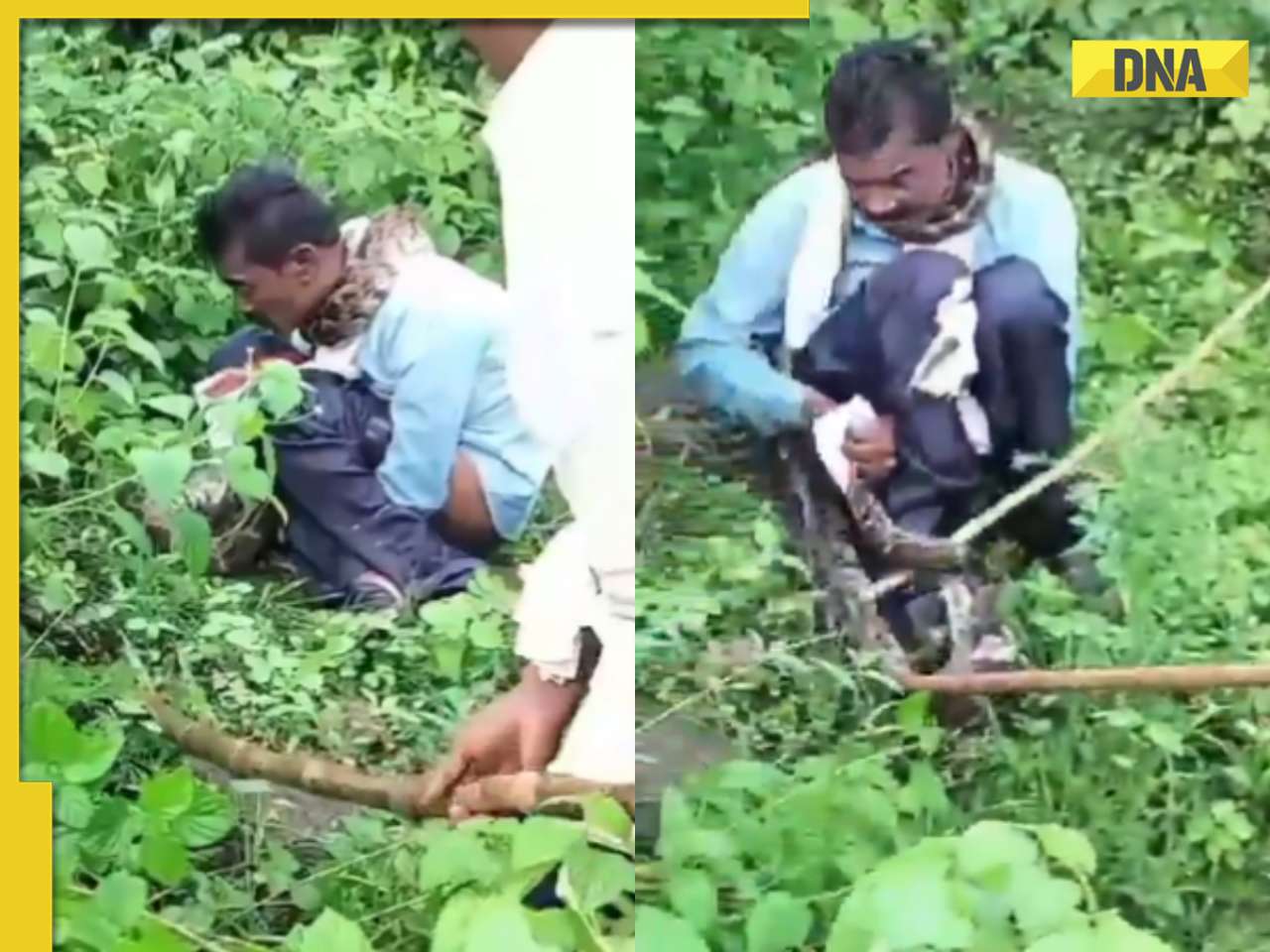

Viral video: 15-foot python attacks and nearly swallows Jabalpur man, here's how locals save him, watch![submenu-img]() 'Anant knows everything': Akash Ambani, Isha Ambani tell Amitabh Bachchan as…

'Anant knows everything': Akash Ambani, Isha Ambani tell Amitabh Bachchan as…

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)