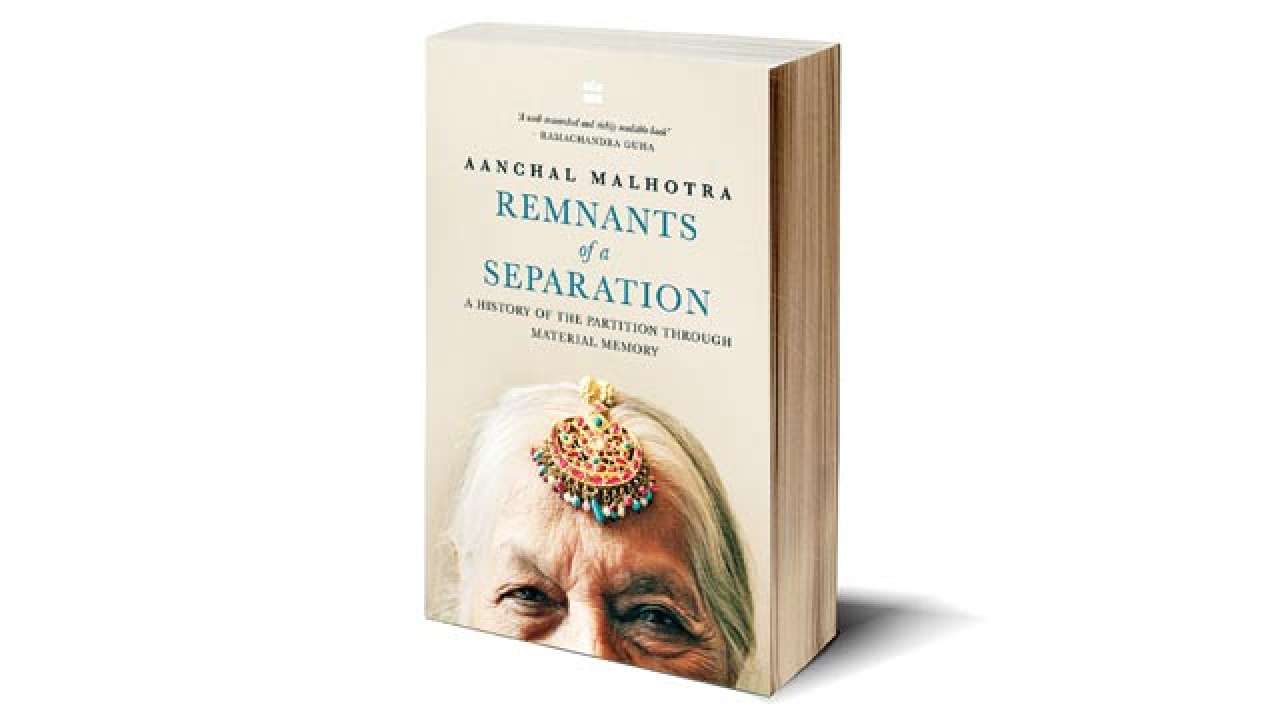

For four years as she recorded endless conversations with strangers, Aanchal Malhotra found herself adrift on a sea of memories anchored by every day objects – old books, a matriculation certificate, a bed sheet, a bagh (traditional embroidered piece of cloth given to brides), a lost dialect, a mang tikka, a pocket knife... "I was consumed by the stories. There came a time when I started having vivid dreams about Partition, as if all the stories that I had heard were yearning to be told and the only way to do justice to them was to write them down," she says. And that's how Remnants of a Separation-A History of The Partition Through Material Memory, her recently launched book, came about.

A vivid collection of Partition memoirs, the book is narrated by the last surviving generation that witnessed it firsthand. Through 19 chapters, Malhotra takes readers through myriad emotions, evoking a way of life fast receding in nostalgia. As she says, "We can't fathom the damage Partition did to them. The least the young can do is read and empathise with with what takseem-e-hind (Urdu for Partition, a phrase used by many of her subjects) entailed."

This same sense of empathy flows through the pages of the book by the 27-year-old. The book began in 2013 as a photo-document of objects that people brought with them when they crossed over during Parition, part of her post-graduation thesis at Concordia University, Montréal. But as she learnt more about the lives of people who shared the objects with her, she realised that a mere collage of photos wouldn't do justice. In a rather sombre tone, she explains how she felt accountable towards those who opened themselves up to her. "There was need for a sensitivity and nuance while narrating Partition's horrors. Some of the things were being shared for the first time. I felt I was being given a gift, with the confidence that I'll handle it with care," says the student of printmaking and art history, who now works with the Red Ink Literary agency in New Delhi.

One such is the story of Delhi resident Nazmuddin Khan, who loved Hindustan and chose to stay back despite all the bloodbath and mayhem. "He gave me a very valuable lesson in communal harmony, something that we need to learn in these times."

A rusted pair of scissors, now used to cut flowers, narrates the tale of how precarious women's safety was at that time.

Then there's the story of Narjis Khatun's khaas daan - a paan serving dish meant for special guests. Khatun migrated to Lahore from Samana, a small town near Patiala; while talking to her, Malhotra chanced upon Samanihahi, a mix of Punjabi and Hindi once spoken by people from Samana. She recalls how Khatun's granddaughter believed it to be a secret dialect invented by her to talk to elders.

Malhotra recounts how, for long, she didn't know that her own grandparents too were Partition survivors and how it required a lot of effort before they decided to share their feelings. "They had a complex gamut of feelings – shame, agony, sadness – and so remained silent. My grandfather was a fiery 19-year-old when it happened. And, perhaps, the regret that he could do nothing to save his land and had to flee, never left him," says Malhotra. The constant refrain when she asked them what happened at the time was "kya badal jaayega", but once they started sharing the past, it was as if they were waiting to be heard. Then it went on for days together," she smiles.

But the book is not just about pain and trauma. "Yes, the horror is etched firmly, but through Remnants of a Partition, I have tried to create a lost epoch. It is about childhood memories, friends and mohallas that have been left behind, but remain an inextricable part of you," she says wistfully.

Malhotra was conscious of the raw nerve she would touch while compiling the book. Age worked in her favour – many of the interviewees thought of her as 'beti' and she too was sensitive and prudent in her approach, never starting a conversation with the trauma of Partition. "We started with innocuous things, gingerly moved towards the object and then Partition. For if someone has to give you something delicate, she has to first trust you," she says matter-of-factly.

In spite of this, she did touch wounds. In Gurgaon, where she spoke to a woman who was orphaned and separated from her sister, only to find her again after more than 10 years, the husband kept glaring at her all through, angry at making his wife relive the ordeal. "The smallness of my life dawned on me increasingly as I listened. The gravity of this reality is mammoth, the pain is colossal, and it cannot be contained in one book," avers Malhotra. Also her reasoning for starting a new contiguous project with her friend Navdha - The Museum of Material Memory, a digital repository of material objects, tracing family histories and roots.

Over time, says Malhotra, as more and more people got to know of her project, they wrote to tell her stories about what their families had as tokens of Partition. "It was not possible to include everything in the book. The museum will provide a collective space to share stories of their struggles, sacrifice, pain and uprooting from their land," she concludes.