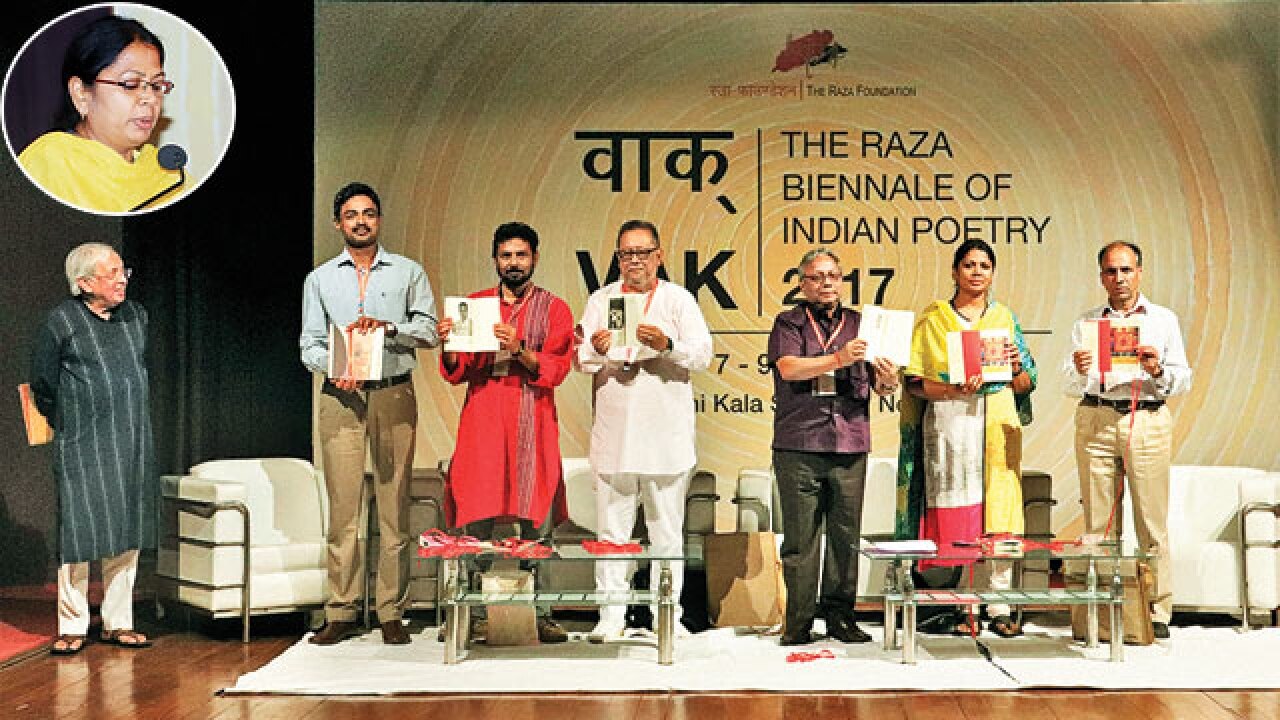

Biennale fever has gripped several parts of India in recent years, but the one that concludes in the capital today is a novel initiative. Called Vak, it is India's first poetry biennale, a two-day affair dedicated to 45 versifiers from 15 Indian languages. Organised and financed by the Raza Foundation, set up and endowed by eminent modernist painter SH Raza during his lifetime to support artists and the arts, the biennale has been conceived by his close friend and acclaimed Hindi poet Ashok Vajpeyi, also a trustee of the Foundation. Gargi Gupta spoke to Vajpeyi about the role poetry plays in the world today. Edited excerpts:

The visual arts was Raza's first love, but poetry was his second. We became close friends because of poetry. Raza used to pick lines of poems and record them in his diary, Dhai Akshar–Kabir's words for love. There are nearly a hundred canvases in which he has used lines of poetry from the Vedas, Upanishads, Kabir, Ghalib, Faiz, even from me.

Two, I think poetry is a sign of conscience in times of strife. We thought this was a good opportunity to put it together, to reveal the plurality of India.

Well, one had to have a name (laughs). Vak is speech. The Indian vision of artistic endeavour was that in the centre is vak.

That's part of the game. The universal indifference to the arts is a fact. One battles that. Nobody will listen to you — that is not reason enough that you should not speak.

We tend to believe that poetry should be like a newspaper report in which everything is clear. "Trump has won the election", a newspaper report says right in the beginning, and the rest are all details. Poetry happens the other way around — if at all. It gives you the details but it doesn't render its truths so easily. Its truth is partly inherent and partly, you have to add your own truth. And we are so used to receiving truths rather than creating truth.

Kalidas was elite, so was Bhavabhuti. Tulsidas was elite, too. He wrote at a time not many could read. The obsession with the popular is itself a questionable notion. Kalidas was never popular. The last poet who was both popular and elite was Rabindranath Tagore.

There has always been a divergence between the popular and the significant. At one point, Sahir Ludhianvi and other good poets wrote for Bollywood. But that (phase) was short-lived. What you have now is mostly mediocre, sentimental poetry. Some of our so-called popular poets are really mediocre.

Politics today is denying plurality, denying ideas, it has nothing to do with memory. We are forced to live in an eternal present; whatever memory, whatever culture there is, is misappropriated. Against all that, the Raza Foundation and I are asserting plurality, respecting dissent, providing forums on which all kinds of plurality are thriving.

The point should not be to explain. We have just asked the poets to read. You have to sit through it. Let yourself be assaulted, taken over, made love to by poetry.